Hands Up, Don’t Shoot: Students Protest Systemic Racism, Police Violence

December 5, 2014

Oberlin students, faculty and staff came together this week to organize and execute a variety of protests, demonstrations and actions that highlighted what they identify as the College’s complicity in the systemic oppression of people of color. While these protests were not the only actions that took place this week, they were among the more heavily-attended demonstrations.

Students Challenge Board of Trustees

Over 100 students occupied the Board of Trustees forum in Stevenson Dining Hall on Thursday, crowding along the walls and dispersing themselves throughout the space in order to ensure that their voices would be heard.

“I look at the disdain in your faces, and I can see that you don’t respect me or the people who look like me,” one student said to the trustees, many of whom were white men.

“Don’t admit students into this college just to make this college look good,” said another.

“You limit access to students of color at this school,” a third said. “You limit our access into your classrooms. Why is it that the only people I know who have ever heard of Oberlin are rich and white?”

The action, which was organized by several students of color, called attention to what many have identified as Oberlin’s institutional marginalization of low-income students and people of color.

Many of the students who spoke at the forum demanded the Board take accountability for what they viewed to be the Board’s apathetic approach, as well as for the racist microaggressions that some used in their responses.

“Hands up,” several students of color shouted when they heard language they identified as violent or oppressive. “Don’t shoot,” the rest of the demonstrators yelled back.

According to College junior and action organizer Kiki Acey, the chant was a way for students to express the pain that comes from destructive and dehumanizing language.

“If they kick us, we will say ouch,” said Acey.

Other students used the forum to address specific concerns and demands. College junior Amethyst Carey asked the Board why the Multicultural Visit Program had been expanded to give even more access to white students, while College junior Lisa-Qiao MacDonald demanded that the trustees take part in anti-racist and anti- oppression trainings — a comment that garnered much support from the protesters.

While these remarks elicited responses from several trustees, many other comments went unaddressed.

“These issues are central to our conversations,” said Board Co-chair Diane Yu, OC ’73.

Other board members agreed and stressed that their goal was to serve students.

“We want to [allocate resources] where they can best be used,” said trustee Alan Wurtzel, OC ’55.

Wurtzel went on to say that the Board was between a fiscal rock and a hard place when it came to earning revenue, as the College has very few income channels and cannot afford to vastly reallocate its assets.

Peters Protest Denounces Respectability Politics

While the Board of Trustees enjoyed pre-dinner drinks in the lobby of Peters Hall earlier that evening, a group of protesters were congregating upstairs.

“Ferguson is all around us. We need to pop the bubble that insulates us from the rest of the world. We do not get to compartmentalize these issues,” said Bautista.

When the time came for the students to interrupt the dinner, they split into two groups. The white students descended the staircase first, filling the lobby with shouts and other loud vocal noises that called attention to the demonstrators. They were soon followed by students of color, who silently dispersed themselves throughout the lobby.

According to Bautista, the demonstration was purposefully chaotic and inconvenient and was purposefully de- signed to have white students enter the lobby first.

“We need to reverse the racial paradigm that is associated with activism,” Bautista said. “Not just on campus, but nationally. It’s a paradigm that allows people to be apathetic and police other students. This policing has been mostly coming from white students on this campus unfortunately, and when you see a cohort of people who look just like you, it’s a little bit harder for you to criminalize them and demean them and invalidate everything they’re saying because they are you.”

While the rest of the students descended into the lobby, Bautista remained on the stairwell to request the crowd take four and a half minutes honoring the memory of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager who was shot by white police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, MO, this summer.

In demonstrations across the country, the four and a half minutes of silence was specifically chosen to represent the four and a half hours that Brown’s body was left lying in the street.

During the silence, trustees craned their necks to see the demonstrators, some of whom were holding posters of other black and brown Americans who have been murdered by white police officers. Others were holding posters of the 43 Mexican students that disappeared in southern Mexico this September.

Other students passed out a list of demands to the trustees, which were a direct reproduction of the demands that were presented at the Board of Trustees meeting in October of 2013.

The demands called for increased institutional transparency, divestment from companies that profit from Israel’s occupation of Palestine, creation of a scholarship program for undocumented students, a ban on fracking on College-owned property and the official formation of an Asian-American studies minor.

“We were highlighting the fact that there has been complicity and inaction [ from the trustees] despite student pro- test,” Bautista said. “How will trustees wield their privilege moving forward?”

Though the trustees and other dinner attendees were largely silent during the demonstration, Dean of Students Eric Estes said the protest had an important message.

“I think they thought it was incredibly powerful,” Estes said. “I was just talking to a trustee who actually occupied this building during the Vietnam War protests. We were having a fascinating conversation… I love and respect our students very much.”

Protesters Unite in Oberlin, Cleveland

Nearly 200 students participated in the national Hands Up, Walk Out day of solidarity on Monday, shouting chants of “Hands up, don’t shoot” and “No justice, no peace” as they marched through the campus and into town.

Protesting against the systemic marginalization, brutalization and dehumanization of black and brown Americans and denouncing police brutality and other forms of racialized violence, the demonstrators called out Oberlin’s administration for its inaction.

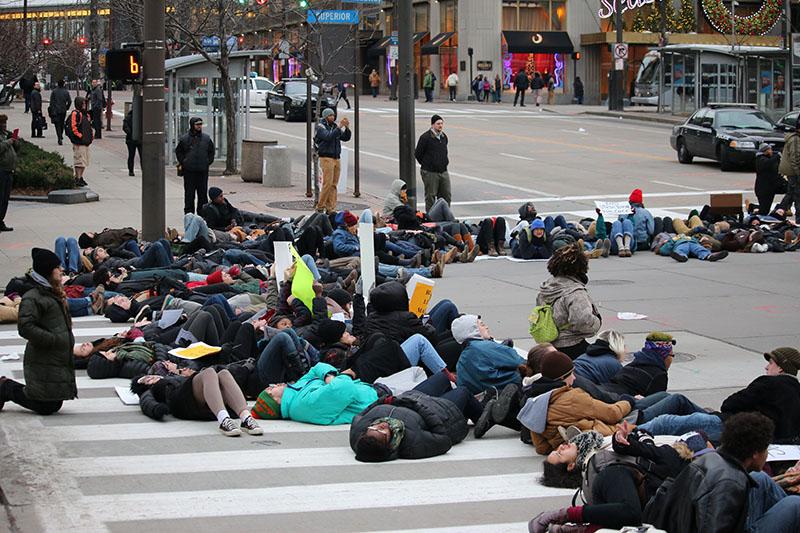

The protest formally started at 1 p.m., when dozens of students walked out of their classrooms and convened in front of the Cox Administration Building. After staging a four-and-a-half minute “die-in” — in which protesters lay on the ground — they advanced toward the King Building, where they weaved in and out of classrooms in an attempt to engage their peers in the action. From there, students marched into the Science Center, through Wilder Bowl and into Bibbins Hall, where several teachers were holding music theory classes.

While some professors allowed students to join the protest or cancelled class, others chose instead to ignore it. Many of the students, however, chose to ignore their professors, and by the time the crowd surged out of the Conservatory, it was over 100 strong.

“No justice, no peace, no racist police,” the students shouted as they headed toward the Oberlin Police Station, where they aimed to hold officers in Oberlin and nationwide accountable for police brutality enacted against black and brown Americans.

After protesting outside the police station, students moved toward Oberlin High School, where they proceeded to inform those exiting the building of how to get transportation to several protests in Cleveland.

Demonstrators then returned to Cox to reconvene and discuss productive ways to move forward. By the time the crowd dispersed, students had formed groups that focused on media saturation, artistic expression, direct action, decompression and community and church engagement.

The Hands Up, Walk Out demonstration was part of many that were organized in response to the recent events in Ferguson. Many communities have been protesting police violence since the shooting, strengthening their efforts when Missouri’s grand jury announced last month that the officer who killed Mike Brown would not be indicted.

A number of Oberlin students have participated in several of these demonstrations, including one that took place last week in Cleveland. The protest, which was organized by Cleveland anti-mass-incarceration group Puncture the Silence, saw nearly 100 Oberlin students stand in solidarity with Cleveland residents who condemned the grand jury’s decision not to indict Wilson, as well as the recent murder of black 12-year-old Tamir Rice by a white Cleveland police officer.

One of the other highly attended actions on campus was Wednesday’s Faculty and Student Teach-In on Ferguson, during which approximately 300 students gathered in King to hear individuals speak on the historical context of police brutality and systemic oppressions of people of color, as well as the ways that students can prioritize activism. The Multicultural Resource Center as well as the Comparative American Studies, Africana Studies and History departments organized the event.

According to College President Marvin Krislov, these initiatives will be taken into consideration as the administration moves forward with its action. In his weekly Source column published on Wednesday, he announced the formation of a working group designed to determine the “best principles and practices for ensuring campus safety in an inclusive and equitable fashion.”

In an interview with the Review, he highlighted the importance of community.

“We recognize that these events are very concerning and upsetting to a lot of people, and we want to be there as a community to support students and others — faculty and staff — who want to talk about this, and I hope that we can figure out educational ways in which we can think about these issues together.”