TED Fellow Questions Sound Perception at AMAM

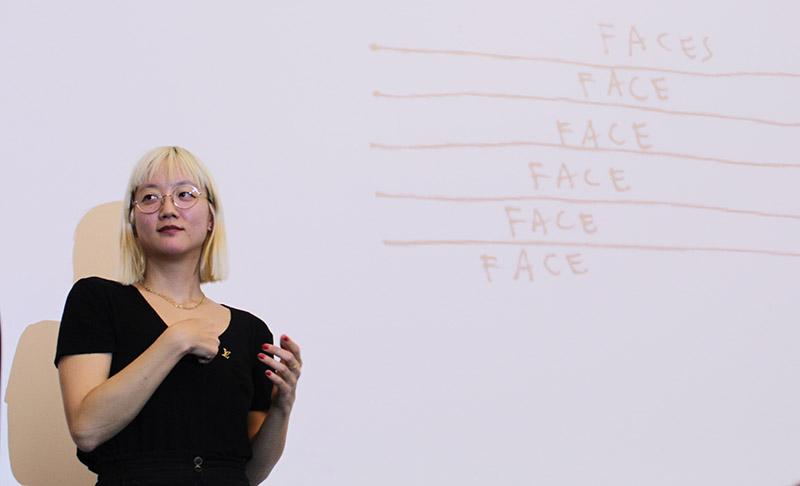

Artist Christine Sun Kim explores conventions of sound at a live musical art exhibition during her visit to the Allen Memorial Art Museum Tuesday evening. A TED fellow whose work has been featured at the MoMA, Kim galvanized Studio Art and music majors alike during her refreshing performance.

February 6, 2015

Multimedia artist Christine Sun Kim often shies away from communicating with the media. Signing to her interpreter, Denise Kahler, Kim explained the reasoning behind this. According to Kim, journalists often box her in as simply a “deaf artist.” Rather than being seen solely in this way, Kim should be seen as a deaf artist who has come to work with sound in a unique, unconventional manner.

Hours before her performance and talk in the Allen Memorial Art Museum on Monday night, Kim explained how she came to experiment with sound. “Sound was a sort of taboo subject” among her deaf friends, but she began to realize that “sound is everywhere” and that “there [are] a lot of social norms and power associated with sound.” A self-described “failed painter,” Kim, who said she previously felt “confined to a piece of paper,” discovered that using sound might be “a good vehicle to communicate my ideas and a good medium to reach a larger audience, as opposed to just the deaf community.”

Kim’s earlier work bridged the gap between sight and sound by using speakers to cause objects, such as strings and ground-up chalk, to move. She said that she “got bored quickly” and has moved on to making art she characterizes as notably different from her early work. Enthusiastically gesturing towards Kahler, she shared a realization that led to this sea change. “I’ve got this huge world out there of sound and music and spoken language and linguistic authority,” she said. Her current work on “unlearning sound etiquette,” she explained, is a paradigm shift for her. She elaborated by saying, “Structure and things are based off the hearing world. So we use things that already exist, that hearing people have created, and we use them to fit what I need them for.” This paradigm shift she mentioned could be felt in her talk later that night.

From outside the room where Kim was to give the talk, a mass of students waited to be let in. Inside the room, ambient sounds could be heard. These sounds were indistinct but hinted at what was to come. When, at last, all of the attendees squeezed in, the room became quiet. She began to type to the audience with an iPad. The room remained silent for the whole introduction, except for the occasional laugh at Kim’s wit. She explained the collection of four sound files that she was to present, Fingertap Quartet, which employs her voice and another male voice.

The first sound file, she typed to the audience, was meant to be “a sound you like and think is good.” The following piece was the converse. The third sound file was meant to be “a sound you like, but suspect might not be good.” The crowd chuckled at that, and even more at the final caption, which was the converse of the third title. Before hitting play, Kim typed out a last couple of things, including that she insisted on using subwoofers for her and other deaf audience members and not to tell her if her sounds were distorted.

The sound files, whose textures Kim had produced with her voice and manipulated electronically, seemed to produce reactions in the audience that a conventional “hearing” person might produce; however, the means of production were unique. “Like, Good” was a call-and-response of different ‘e’ syllables between her and her sonic partner, Jamie Stewart of California postpunk band Xiu Xiu.

The audience, which seemed not to know what to expect, was clearly interested and listened intently. Kim’s recorded voice went through a series of “ee”s and “eh”s that gradually became more affected as the sound progressed. “No Like, No Good” began with chromatic note shifts that created a more dissonant feel. Grating, tearing, desperate and droning, this sound file opposed the first file’s title and content. Kim produced all of these textures with her voice and manipulated them electronically. “Like, No Good” included heavy breathing, slow-motion sounds and bomb dropping noises, creating a sexually charged sound. “No Like, Good” was consistent with its title. It elicited bodily reactions from audience members, with several concertgoers breathing along to the recording by the end of the piece.

Kim didn’t follow typical musical conventions, but the result was musical. Her music had a definite pulse, accentuated by her subwoofers. Audience members could be seen swaying along.

Kim’s music was expressive in a visceral sense. After showing her music, she presented other sound projects and visual art. Kim’s visual art was just as unique as her music. She used four lines in her portrayals of musical staves instead of five because the sign language symbol for musical staff has only four lines. She also questioned the line between silence and sound with her drawing “The P Tree,” which shows a continuously subdividing pianissimo. Her talk was well-received by the students, almost all of whom stayed for the whole event despite a lack of seats and an oppressively hot room.

Conservatory senior Sivan Silver-Swartz was a key force in bringing Kim to Oberlin. The day following Kim’s talk and performance, Silver-Swartz explained why the Modern Music Guild decided to bring Kim to campus. “We often book … musicians, composers and artists who kind of fall through the cracks in terms of what the other official organizations bring [to campus],” he said. Silver-Swartz mentioned that he saw the event as bringing together art communities. “I thought it was kind of a nice opportunity to sort of bridge the gap between … the Studio Art world and the music world, which seem often to be very separated,” he said. “People don’t go to each other’s events, so it seemed like a cool opportunity to get both communities [together].”

In reaction to Kim’s performance, Silver-Swartz recalled a moment when she flashed the word “empowerment” on the screen. “I think her art really is a lot about empowerment,” said Silver-Swartz, carefully adding that, although she said that her work was not overtly political in nature, “For many people, [Kim’s art] has political implications.”

One student who seemed particularly intrigued by the talk and performance was double-degree first-year Mohit Dubey. Dubey, a Classical Guitar major in the Conservatory, plans on majoring in Physics in the College. Dubey’s love of music and science has led to his interest in computational neuroscience. He said he is working to “get a computer to hear like the human brain.” Dubey said that he found Kim to be particularly interesting in terms of how “she’s kind of reinterpreting … what to think of as music and sound.” Some of the questions she raised resonated deeply with Dubey. “What does a dynamic mean? Can you ever achieve a true silence?” he asked in reference to “The P Tree.” Dubey briefly explained that through an experience called “Hebbian learning,” our neurons “become tuned” as we hear things. He continued to explain that his study of Hebbian learning pertains to Kim’s work because “she doesn’t have that experience. Her experience of sound is mostly a visual and sensory experience.”