Tales from Oberlin Winter Break Quarantine

After over 150 students tested positive with COVID-19 just days before winter break, many were left with the daunting task of isolating in campus housing over the holidays. Most students look to winter break as an opportunity to retreat into the comfort of a childhood home, a reprieve from uncomfortable dorm beds and bland, nutrient-deficient cafeteria food. But the students who tested positive were suddenly confronted with the impossibility of returning home and the imminence of complete isolation; they had to establish their own holiday traditions and find ways to escape the monotony.

Unfortunately, I discovered I was COVID-positive only a few days before I was set to fly home. Within two hours of receiving my results, I contacted the Rev. Dr. David Dorsey, director of religious life, wondering how I could pick myself up and make the most of the holiday.

“Hi David,” I wrote in my email. “I just tested positive for COVID, and in all the things that were hitting me about the reality of this, it occurred to me that for the first time ever, I’ll be spending Christmas completely alone. I know many of my peers are probably in the same boat, stuck here in Oberlin for the holidays with only Stevie food and our heaters to keep us company. Working with Barefoot and [the Office of Religious and Spiritual Life] has been the closest a College organization has felt to the warmth of a family — I suppose this is what made me think to reach out to you and ask if there’s anything that can be done.”

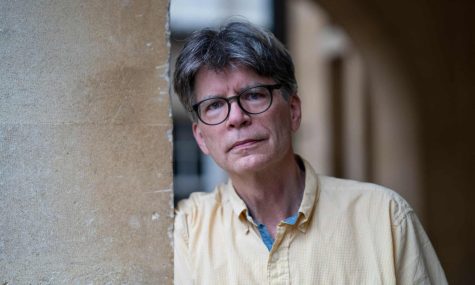

I met David while working on a piece for the Review earlier in the year, and remembered him as a remarkably generous figure — the kind that offers you a cup of tea anytime you come by to chat. In a series of emails, Zoom calls, and phone conversations, David and I etched out the details of what efforts ORSL could make to help students like myself. We forged a sense of connection I could get from little else, and my dedication to organizing something for other sad students helped me escape the loneliness of isolation and remain in the real world.

“It’s been my experience that Oberlin students really work hard to be present for one another, make connections, and support the mental health and the experience of one another,” David said. “I think [the break] was particularly challenging, but it’s always inspiring to be around that level of effort.”

Despite our initial ambitions to organize an event like an outdoor, takeaway holiday meal or a gift exchange for socially-distanced companionship, the fruit of our collaboration turned out to be an email detailing the offerings of the community at large for any students spending winter break at Oberlin.

“There were a lot of really fun, more zany things that we wanted to do, but we would have needed to reach out to students,” David said. “We really had to let this get passed along by students by word of mouth, so that’s how the communication got out there.

Some students chose to isolate with other isolated students, forming small reverse-pods for positive cases only. Together, they acquired houses to stay in and struggled through their sore throats and fatigue with company.

After College third-year Dina Nouaime’s entire friend group tested positive, they decided to rent an Airbnb in Cleveland together and manage their symptoms as a group.

“This was my first time being away from my family during the holidays,” Nouaime said. “But I was really fortunate to be with the people who I was with at this point in time, and despite being stuck in a house together, we were able to find joy in crafts, puzzles, and a lot of movies.”

After a few days, the house fell into a rhythm.

“A typical day started around 2 or 3 p.m. because we were all extremely fatigued and filled with brain fog,” Nouaime said. “We’d make breakfast, but it was more like a lunch-dinner-‘linner’ type of thing, and then we would watch a bit of Gossip Girl. After, we would try and get some work done, but the brain fog prevented that. We would make one more meal around 11:59 p.m., and then we would stay up and watch a few more movies and go to bed around 3 or 4 a.m. A very healthy approach to combating COVID.”

College second-year Liam McGovern-Junco also stayed in this Cleveland Airbnb, noting that even the 30-minute drive out of Oberlin helped dull the painful monotony of winter on campus.

“It was really nice to have a little change of scenery,” he said. “I could go for a walk and see a neighborhood that I had never seen before.”

On the third day of my own isolation, I acquired a tree. A friend’s parents had shipped him a small Charlie-Brown-esque Christmas tree, and he told me it was mine to take. Our friends decorated the tree with cheap ornaments, garland, and colored lights. Tree in-hand, I trudged across campus to my dorm, shattering half the ornaments on the way, and plopped it down in front of my bed.

Among the nihilistic and shapeless days of isolation, I find it’s good to impose a little ritual. That night, I pretended I had company: I turned on the Christmas music and made a big show of plugging in the tree and turning off all my lights. I treated my careful adjustment of all the scattered decorations on the tree as if I was decorating it for the first time. I also found some paper snowflakes cut up by students in the library of my dorm, leftover from the night they decorated our lounge before break. I attached each snowflake to some red yarn and taped them to the ceiling. Looking around at my handiwork, it felt, for a little bit, like being home.

By that point, the Faculty in residence was the only other person left in my dorm; she, sick herself, began checking up on me and leaving little gifts in Trader Joe’s bags on my door handle: Christmas-themed chocolates; a wrapped plate of homemade chicken olivye, a kind of Russian potato salad she said her mother always makes around the new year; a grapefruit.

I made lists in my head of the things I missed: candles, eggnog, hot chocolate; my tradition of wrapping Christmas gifts in brown paper; the way it creased and yielded to wrapping; the sound it made when cut. I missed Christmas movies, which I’ve learned are only good when you’re forced to watch them, fattened up on the couch after a meal. I remembered the sounds of my grandparents’ house, always swelling with holiday music and occasionally jingling with the sound of the tiny round bell my grandfather always tied on a string to his belt loop.

“I think when vulnerability is forced on us — testing positive and then having these mandates placed on us for the safety of all — … [it] can [be] really hard to choose to be vulnerable,” David said. “And yet, in these holiday seasons and in these moments that we might have been with our family, it’s incredibly meaningful to be in the company of people who might choose vulnerability, and to grow their relationships and to deepen trust. It didn’t surprise me, but what I was pleased to witness was the way in which students in really tough circumstances were still choosing to trust one another, still choosing vulnerability for a larger good.”

My worst fear upon realizing I’d be spending Christmas in Oberlin was how easy it might be to feel nothing. I imagined myself waking up on Christmas morning to find it was just another day. To prevent this, my best friend managed to snag me a gift from CVS Pharmacy and wrap it in the tissue paper from her Doc Martens box before she left for break.

When the day came, I woke up before the sun rose and observed an important family tradition: waiting. Waiting for the rest of the family to wake up; waiting for breakfast to be made and eaten; and, in this case, waiting to be Zoom-called by my mother, who set me down to watch my family eat their Christmas breakfast and tear into their gifts. My scrounged CVS gift — those Danish cookies that come in tins, a bit of peppermint bark, and a set of gray press-on nails that were so long I couldn’t use my phone — made me smile. I felt like a child again, playing with the best toys in the world.