Maslenitsa Gathering Highlights Crisis in Ukraine

The Russian department’s gathering for Maslenitsa was punctuated with the ritualistic burning of the chuchela effigy in Tappan Square.

This Saturday, the Russian department hosted a gathering for Maslenitsa, a Slavic holiday traditionally marked by a week of festivities before the start of Lent. The holiday has over a decade-long history of being celebrated at Oberlin. This year, students and faculty came together for an untraditional Maslenitsa. The mood, far from celebratory, was darkened by the ongoing war waged against Ukraine by Russian President Vladimir Putin. The event shed light on the crisis in Ukraine, while simultaneously serving as a reminder that atrocities committed by Putin should not result in a wholesale rejection of Russian cultural heritage.

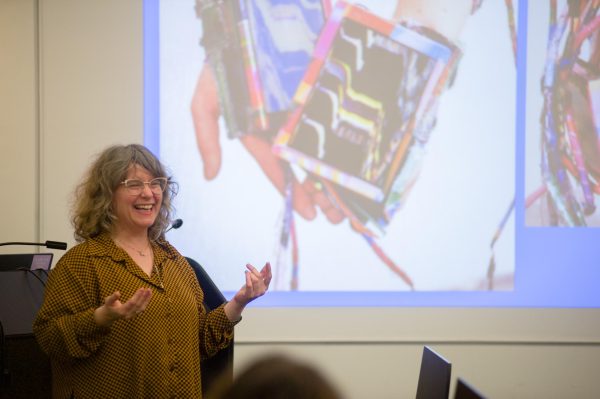

Faculty in Residence and Lecturer in Russian Maia Vladimirovna Solovieva described the origins of Maslenitsa at Oberlin.

“[After a] long, long winter, students get crazy and bored,” Solovieva said. “Someone approached me in the Russian house, saying, ‘Maia Vladimirovna, let’s burn something!’ I said, ‘In order to burn something, you have to build something.’”

Maslenitsa, which has pagan origins, symbolizes the battle between winter and spring at the threshold between the seasons. Spring’s eventual victory is heralded by the ritualistic burning in effigy of the chuchela (or “scarecrow”), also called Lady Maslenitsa, who symbolizes winter. Students at Oberlin have historically marked Maslenitsa by fashioning a doll out of scraps of cloth and burning her in Tappan Square.

“We believe that, when this chuchela burns, winter goes away, all bad things go away, and new life comes,” said Daria Makarova, the Russian department’s Fulbright Scholar. “As you see, winter has gone, so maybe it’s because of burning the chuchela.”

In past years, Maslenitsa was a day of song and dance, as well as an opportunity for students in the Russian department to get acquainted with Slavic customs and foods, practicing their Russian vocabulary while learning to fry traditional pancakes called blini. To celebrate as normal, heedless of the war in Ukraine, would have been impossible.

“Originally, the event was planned for March 5, and war started on [Feb.] 24,” Solovieva said. “I was so close to canceling, my colleagues and I were talking a lot about it, and I decided, ‘Okay, I’m gonna do it, but it has to be a different Maslenitsa.’ … It wasn’t a celebration, and it was clear from the beginning. We wanted to talk about the tragedy — what happened, why it happened, but we also wanted to give people [the] educational part, and some sort of hope. If it is a celebration, it’s a celebration of life. It’s a simple reminder: we continue to live, and we have to continue.”

At an informational session before the burning of the chuchela in Tappan Square, faculty and students spoke about the different tone of Maslenitsa this year, and why they chose to commemorate the occasion despite Russia’s shameful position on the international stage.

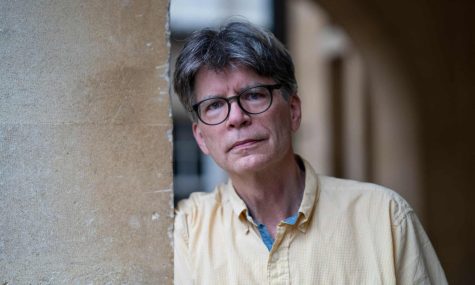

“Maslenitsa is a week of excess and celebration, leading up to a longer and quieter period at traditionally 40 days, a difficult, long time,” said Tom Newlin, chair of the Russian department. “A period of self-denial, but also reflection and contemplation and even atonement. And we’re marking Maslenitsa — maybe not quite celebrating it, but marking it. … Actually, we’ve already entered that period of Lent, of reflection. I think this is in that spirit. And Lent is a time of giving things up, of casting things off that you maybe feel you need. And I think there’s a temptation … to cast off Russian culture; throw the baby out with the bath water, so to speak.”

While underscoring his ultimate concern for Ukrainian suffering, Newlin argued that Russian culture, in this moment of Russian ignominy, should retain its merit.

“Russian culture has a lot to teach us about what’s going on right now, even as Russia is the horrific aggressor,” he said. “I think if [Putin] had read War and Peace, he might have found fair warning of what happens to an alien army, when unprovoked it invades another land.”

Katie Frevert, fourth-year Russian and East European Studies, and Creative Writing major, is experiencing an internal conflict in weighing in on the war in Ukraine. As a student heavily involved with the REES department and yet not materially affected by the tragedy unfolding abroad, she finds herself being more intentional about the implications of her coursework.

“I think in some ways, the fact that we’re all gathering now — despite COVID, despite the war — is an act of solidarity in and of itself,” Frevert said. “And showing that we, in America, do not conflate Putin with the people of Russia. And that we understand that the citizens of a nation are not represented always by its leader. And that, I don’t know — that we are capable of understanding what it means to resist, and what it means to understand a culture besides just on a surface level. And I think that gives me hope that what I’m doing as a student of Russian is useful in some way. And that I’m not just studying the language of an oppressor, I’m studying the language of people who are resisting the actions of their government.”