State Honors Famous Baseball Alum

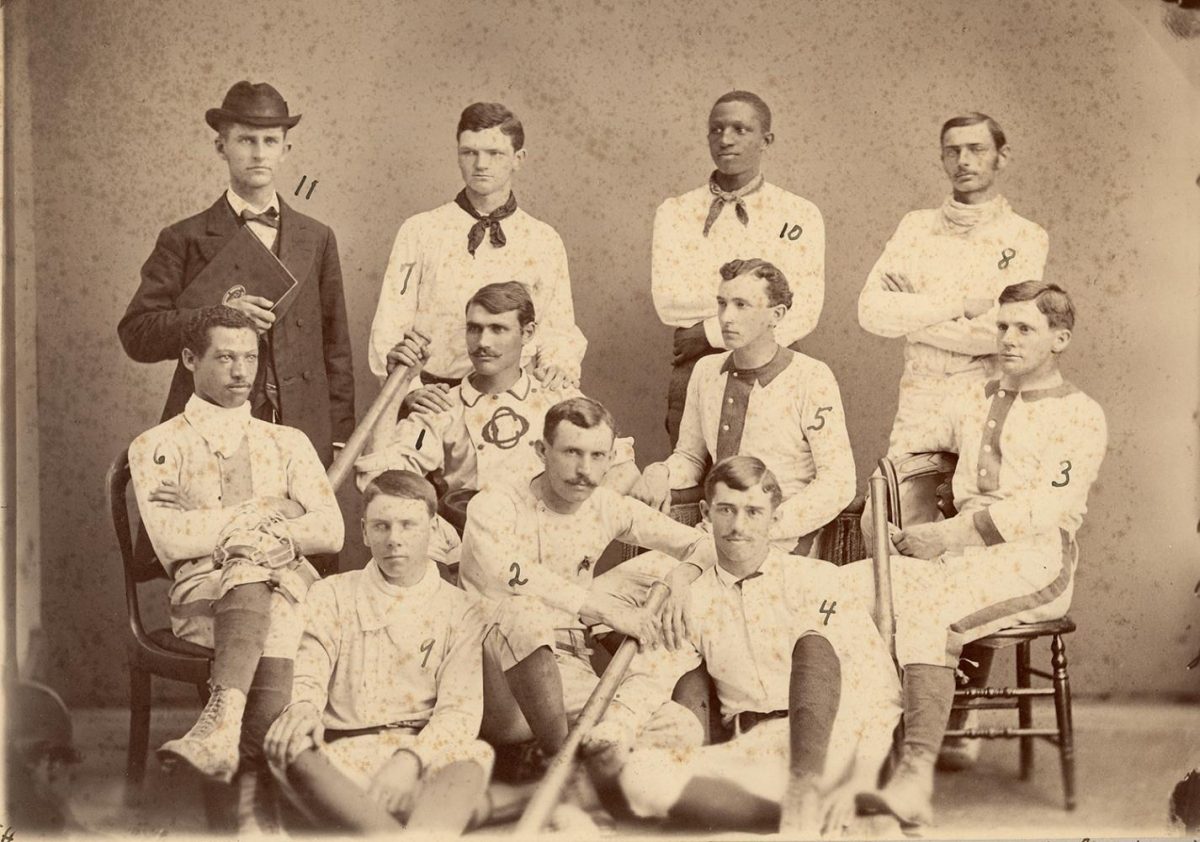

Photo Courtesy of Oberlin Archives

Moses Fleetwood Walker, 6, was a member of Oberlin’s first varsity baseball team in 1881. His brother Weldy, 10, was also on the team. They went on to become the first and second African Americans to play in the major leagues, respectively.

A bill honoring the late Moses Fleetwood Walker, the first African-American man to play under contract in the major leagues and a member of Oberlin’s first baseball team, was signed by Governor John Kasich Tuesday after its first two failed passage attampts. Walker’s birthday, Oct. 7, will be recognized annually as “Moses Fleetwood Walker Day” in Ohio beginning in 2018.

House Bill 59 was sponsored by Democratic Representatives David Leland and Thomas West and was approved unanimously by the Senate during its third attempt at passing. The first time the bill was introduced, it failed to clear the House; on its second go, the bill passed the House but was rejected by the Senate.

Walker was born in Mount Pleasant, Ohio on Oct. 7, 1856. He enrolled at Oberlin College in 1878 at the age of 20. He studied philosophy and the arts, which would help him become a businessman, inventor, newspaper editor, and author later on in life. Walker joined Oberlin’s first-ever varsity baseball team in 1881.

According to the GoYeo, Oberlin’s official athletics website, in 1922 Walker was asked via a questionnaire about the influence of his time at Oberlin on his post-grad life; he merely wrote the word “excellent” and underlined it.

Early in his baseball career, Walker was a leadoff hitter and barehanded catcher for the College’s preparatory baseball team. In 1881, Oberlin lifted its ban on off-campus competition, giving rise to Oberlin’s first varsity baseball club. Walker’s younger brother Weldy, a first-year when Moses was a senior, played for the Yeomen as well. The pair were recruited to play at the University of Michigan after an exhibition game in which Oberlin beat Michigan 9–2.

Walker and his brother continued as the first and second people, respectively, to break the color barrier in the major leagues. Walker caught for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association in 1884, playing 42 games for the club before being cut due to injury.

Although baseball fans globally recognize Jackie Robinson as the one to have broken the color barrier in Major League Baseball, historians at the National Baseball Hall of Fame claim Walker was actually the pioneer. Robinson stepped onto the scene on April 15, 1947, six decades after Walker played. A picture of Walker and his Toledo teammates is on display in the Cooperstown museum.

“Though [Walker’s] name is relatively unknown compared to Jackie Robinson’s, he was the first to break the barrier which prevented Black men from playing organized baseball,” Senator Edna Brown said at the hearing of the bill.

Rep. Leland said that Walker’s baseball career is an important part of American history that needs to be recognized.

“The Moses Fleetwood Walker story is an American story about a constant need to fight for justice, equality and freedom,” he told The Undefeated.

Although Walker’s legacy extends to every level of baseball, the place that saw him grow into adulthood also feels his impact to this day. Fleetwood’s experiences continue to inspire the College baseball team, among others, a century and a half later.

African American outfielder Lawrence Hamilton, a first-year on the team said that the College’s commitment to diversity in sports stemmed from leaders like Walker.

“It’s good to see that there’s more diversity on the team and in sports [now],” Hamilton said. “It makes me feel comfortable when I’m playing. I have a group of friends. It’s good to get that [inclusivity] back into baseball.”

For Head Baseball Coach Adrian Abrahamowicz, it’s important to keep Walker’s legacy in mind while leading his team.

“Obviously your history is a big piece in what you are,” Abrahamowicz said. “The school’s reputation as the first school to admit African Americans and women kind of ties in perfectly with the athletics’ reputation. Having somebody like Moses Fleetwood Walker as part of your history just kind of brings something special — things are inclusive, how they are supposed to be.”

According to Hamilton, the Yeomen baseball team has a record number of African-American players this year.

“Since [Walker], there have been bits and pieces of African-American baseball players at Oberlin,” he said. “But this year we have a total of six or seven, which is unheard of. For example, in the major leagues right now, there are only about 60 African-American players. Starting at the college level, getting more African Americans involved in baseball, recruiting them to come in plus the academics — it’s good to be back on the right track.”

Walker, who died in 1924, was inducted into the Oberlin Hall of Fame in 1990. 26 years after he passed, the Oberlin Heisman Club financed the erection of a headstone on his previously unmarked grave at the Steubenville’s Union Cemetery.