In The Locker Room with Professor and Columnist Kevin Blackistone

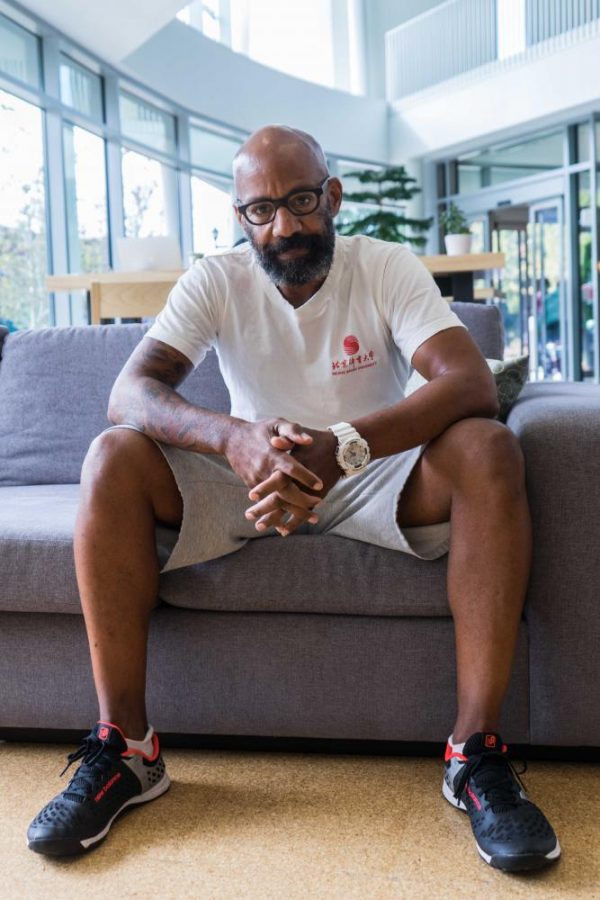

Kevin Blackistone, sports journalist and professor at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland.

This week, the Review sat down with Kevin Blackistone, ESPN and NPR commentator, Washington Post columnist, and University of Maryland journalism professor. Blackistone has enjoyed a journalism career that has spanned more than 30 years, and while he mainly writes about sports, he also covers politics, news, business, and economics. He also makes frequent appearances on ESPN’s Around the Horn, a sports debating show that covers current topics of contention in sports.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kaepernick’s protest of the national anthem has been a huge topic of contention in the news these past few weeks. How do you think the protest has changed since Kaepernick first started kneeling a year ago? Do you think it’s favorable for the movement that lots of people are joining in?

Just the fact that you call it a protest is evidence that what Kaepernick started in August 2016 has been completely usurped, and has been reduced, really, to what I would consider theater. We watch the beginning of NFL games now just to see if a player is going to kneel, sit, lock arms with a teammate, raise a fist, if they’re going to do any of this in conjunction with owners and coaches — yet no one is asking, “What are they demonstrating about?”

One year ago, it was clear that Kaepernick was demonstrating about unchecked extrajudicial killing and brutality against Black males in this country. It has been morphed now, however, into something that Donald Trump said about NFL players and their mothers, into signs of unity among players, into demonstrations that are no longer even related to the national anthem. Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys and a staunch opponent of any sort of protest involving the national anthem, even had his team kneel and then stand up before the anthem even started. I don’t even think this is a protest anymore. It’s more like a demonstration that has become part of the theatrics of the production of the games. Fox TV recently said it won’t even broadcast what goes on during the national anthem anymore. It’s been really watered down and diluted, unfortunately. What Kaepernick was originally doing was protesting, but what it’s become now is a rebuttal to Trump, and all of a sudden, a number of NFL players got their spine and decided to demonstrate against that. Yet still, we don’t see a majority of players doing anything. It’s really been lost.

Some Oberlin athletes, such as the members of the Varsity Field Hockey and Volleyball teams, have practiced kneeling during the national anthem in their recent games. Do you think this kind of protest has any place on a college campus, where essentially anything that students participate in and identify with can be used as their springboard for social action?

This protest absolutely has a place here, as long as everyone knows why they’re kneeling. Are you kneeling for the reasons Kaepernick knelt? Are you kneeling because of what’s happened in the last few weeks regarding Trump? Are you kneeling for Tamir Rice in Cleveland? Are you kneeling for better food on campus? Protest has to be defined, direct, and consistent, and as long as you have reason and purpose and people understand, I think that’s fantastic.

Historically, NBA players have always been unified in efforts to promote social justice. What do you think this means for the Golden State Warriors to issue a statement not to visit the White House? In situations like this, what is the responsibility of athletes like Stephen Curry and LeBron James to use their platform for social justice?

There’s lots to unpack there. In some instances, it is unfortunate that we place these expectations and make these high demands of athletes simply because they are athletes. I think we should all be involved energetically in our democratic process, regardless of one’s profession, location, or station in life. Also, we should not be so quick to blindly praise the NBA. Let’s praise the players, but be wary of praising the organization as a whole. In the NFL, you see 1,700 members, a much bigger group with significantly different career spans than those of the NBA. When an NBA player says or does something political, it’s easier for them to coalesce. Good on them for being steady and making their voices known. But in some instances, we are too quick to praise. We were too quick to commend Adam Silver, a longtime NBA official who reiterated that the NBA expected players to behave in certain ways during the playing of the national anthem and when the flag is raised.

Remember, the WNBA scrutinized the Minnesota Lynx, who protested in the aftermath of Philando Castile’s death. They refused to talk to reporters after a game about anything other than police killing and brutality, and the WNBA eventually came down on them. The NBA is recoiling again to its corporatized leadership, and its future rests all on the players, not on the league. This presidency has completely changed the dynamics of going to the White House. It’s no longer just a ceremonial thing, it has politics attached to all sides of it, as this presidency is so steeped in racial politics that no one can ignore.

ESPN Broadcaster Jemele Hill came under fire for publishing some tweets accusing Trump of being a white supremacist, which almost cost her her job. How do you think ESPN handles covering sports in the Trump era, and how appropriately do you think they responded to Hill’s tweets?

I think the two are a little separate. Quite some time ago, there was an “all hands on deck” meeting for ESPN employees, which established an edict about what employees can and can’t do on social media. In the aftermath of the tweet debacle, Jemele admitted she violated that code. Having said that, what happened to Jemele is also a representation of where we are today in the world. A week ahead of her tweets, Ta-Nehisi Coates excerpted an entire chapter from his new book which gave a nuanced and brilliant argument that Donald Trump is a white supremacist. In an un-nuanced way, Jemele Hill in 140 characters very emotionally spat out that “Donald Trump is a white supremacist.” Any time you use nouns like that, it’s gonna get you in trouble, especially given the platform she has. Had she written that tweet in a column, rather, and been able to unpack it, she would’ve been in a much better space to defend herself.

ESPN has also admitted that they have been a little clumsy in handling critiques of their politics. Maybe some of us who work there have been clumsy in the way that we’ve gone about critiquing the current political climate, but it’s tough and it’s just a reminder that politics have always been a part of sports, and sports always a part of politics. This isn’t the first time we’ve had these kinds of debates intertwined.

How has race affected, or posed obstacles, in your job as an African American sports journalist? How has it changed throughout your career, especially in the past year of Trump leadership?

For me, journalism has always been about advocacy, especially for the progeny of enslaved Africans in this country. My original masters thesis was actually about the use of pamphlets by African Americans in the 19th century, most famously Walker’s Appeal. So for me, race is not a hurdle or something I have to navigate; it’s something I try to engage with every time I write. I’ve done news, investigative reporting, and economics, so when I moved into sports, the first column I wrote was about a discrimination lawsuit brought against the Denver Nuggets by their recently fired coach. He had been fired by the two new owners of Nuggets, who were the first Black owners of professional sports team in America, and I wrote about how specious his lawsuit was. If I’m not gonna write about sports from the perspective of being a person of color in this country, then I’m not doing a service to our profession or the public. Then I’m just doing what’s been done since the first sports story written in this country hundreds of years ago.

As a professor of sports journalism, what are the important values you try to impart to your students, many of whom are presumably aspiring journalists?

At the University of Maryland, I teach two courses. The first, in the spring, is on the skills of sports reporting and writing. Essentially, I give students the playbook on how to report and how to construct a story, I send them out into the field, and they bring back a product. I lay out to them what’s important in the digital age — in terms of what kind of story they ought to produce — and encourage them to include video and at least audio with their story. I teach students to be curious, because if you want to be a journalist but you lack curiosity, you should find another profession. I try to emphasize to people to be good writers and teach what good writing is.

The other class I teach is a sports and culture class, which is now called Sports Protest and Media, because people got so excited about Kaepernick. I came to the realization that people’s understanding of protest within sports is very shallow, and people don’t understand that politics and sports have gone together for as long as one or the other have existed. They don’t know that Kaepernick is not the first person to use sports as a platform for protest, but it goes all the way back to the 19th century and relationships between sports management and labor. I want people to have an understanding of that history, and there are a few themes I like people to understand: one, that there’s a symbiotic relationship between sports and sports media — which is difficult sometimes for ESPN because it’s such a behemoth that it makes it difficult for it to exercise its journalism sometimes — and two, that there is an element of patriotism, nationalism, militarism that has always been a part of sports, which has shown what an uncomfortable and controversial place sports can be. The Kaepernick thing wouldn’t be an issue had the NFL not — in 2009 — decided to make the anthem a part of the “theater,” and demanded that players be on the sideline for the anthem and flying of the flag. That was a conscious political decision by the NFL, just as much as it is a conscious political decision by Kaepernick not to take part in it the way they want him to. There’s a lot going on there; sports are a lot more complicated than they ever appear to be.