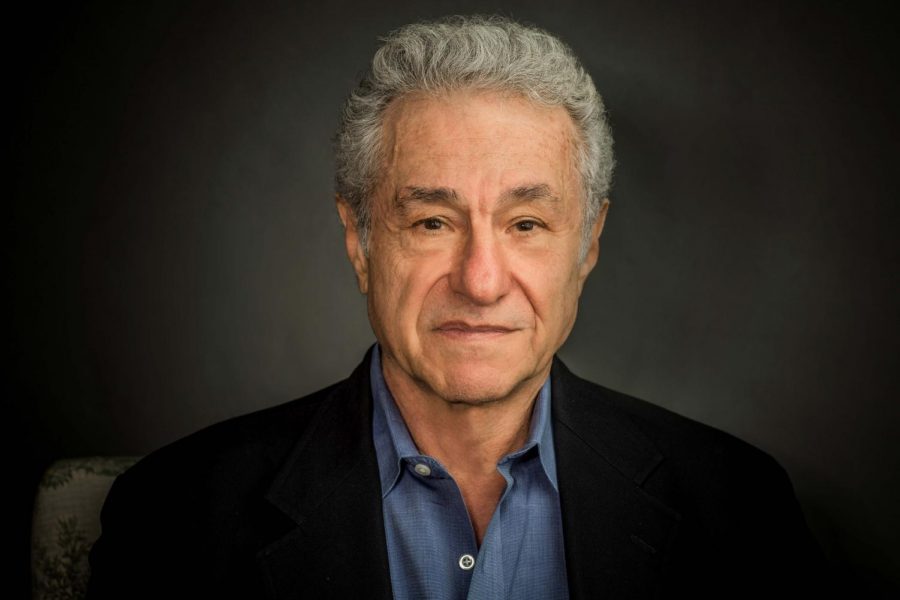

Gar Alperovitz, Historian and Professor of Political Economy Oberlin

Gar Alperovitz came to Oberlin as one of the speakers in The State of American Democracy: A National Conversation, a three-day, non-partisan discussion about the state of democracy in the U.S. The conference examines how the U.S. ended up in its current polarized state, and how we can bolster the resilience, fairness, and stability of our democratic institutions. Alperovitz is a historian, political economist, activist, writer, and former government official. He was the Lionel R. Bauman Professor of Political Economy at the University of Maryland for 15 years. He is the president of the National Center for Economic and Security Alternatives, and is a founding member of the Democracy Collaborative, a research group investigating ways toward community-oriented change and the democratization of wealth.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you end up in your field?

I’m the co-founder of something called the Democracy Collaborative, which is an organization building different ways to transform and democratize the ownership of wealth, the most obvious one being co-ops, but also [things like] city municipal ownership — different kinds of democratic ownership. One of the big projects is called the Next System Project, which is a project of the Democracy Collaborative. That’s attempting to open up a sophisticated, reasonable debate about what is the inevitable next system beyond corporate capitalism, beyond state socialism. What makes sense? What do we want? How do we think about that rationally? What are the stepping stones — projects that we can see that look like they might be a piece of it? It’s mainly about ideas at this stage.

How does that pertain to this conference?

It’s very hard to have democracy if the institutional substructure of the system is so heavily weighted against democracy. In particular, corporate power and the ownership of wealth is extremely concentrated and plays a major role in politics, and it kind of bends away from “one person, one vote” in practice. This has been studied by political scientists forever, but it used to be that labor unions partly balanced the power of corporations and wealth ownership. But they’re pretty much over in the United States and in many parts of the world.

Is there a way to think about, over time, building up the next system that would be democratic, ecologically-sustainable, dealing with racism in a decent, intelligent way, supportive of liberty, dealing with planet changes? The term I like best is “architecture.” What’s the architecture or relationship between worker and company? How would you design it if you were really thinking about democracy and ecological sustainability?

Can you elaborate on the racial component of this?

People don’t realize that we are one of the few pro-democratic systems which is fundamentally divided by race. It was shocking to me that it took 100 years after the end of the Civil War before the civil rights laws were passed. And up until that point, the South was a hostage nation, and a hostage part of the country. Think of it … 100 years after the Civil War.

We’ve got a long way to go, and the thing to notice is that it’s unusual. England isn’t like that; Denmark isn’t like that; Sweden isn’t like that; France isn’t like that. We have a fundamental division on racial grounds based on the history of slavery. It’s a very unusual and dangerous and inhumane system that has to be corrected. Oberlin is a place where the first part of that was dealt with. It has a great history of dealing with race.

During your talk, you mentioned that Cleveland has an interesting co-operative system. Can you elaborate on that?

Cleveland has one of the most interesting models in the advanced world. It’s a pioneer. It’s in a neighborhood, and in the middle of the neighborhood is the Cleveland Clinic and Case Western Reserve University and one other large institution, right in the middle of a very poor neighborhood with about 45,000 people where the average income is $20,000 a year.

The program is called the Evergreen Project. [They made it] a non-profit neighborhood corporation attached with their own companies which are locked in and can’t move to the suburbs, so there’s a major industrial scale — probably the greenest industrial scale in the Midwest. There’s a huge modern greenhouse, which has the capacity to conduce something like 3 million heads of lettuce a year — lots of herbs. It’s all worker-owned, but attached to a non-profit, something in the neighborhood that can’t move, and so by design it’s trying to build a neighborhood. The other one is an energy and insulation company that’s in lights and solar installations. It’s being picked up in other countries. There’s a big one that’s starting in a city called Prestin, in England. The Labour Party has gotten interested in the model, so we see a lot of pickup on it now.

What might that do for workers who live in these neighborhoods?

First, it’s a good income, a stable income. There are good loans for housing, [there are] free training programs, many are ex-felons but there’s no discrimination, there’s training in part of the participatory democracy company, good jobs. When it works — and it’s been working — in these first three we’ve had about 100 employee-owners now, and I think that’s expanding.

What are your thoughts on the American Democracy Conference and how it can improve the conversation?

It’s an important initiative, and there are going to be four or five of them in different parts of the country that’ll catalyze this discussion. At one level it’s about very traditional issues, like voting, parties, and finance of elections, which is very important. But it’s opened up some of these larger systematic questions. Who owns the companies? Who owns the stocks? Can we get participation in the workplace as well as in politics? If you can’t do that, then can you have democratic politics if the concentration in income and wealth is not democratic? It’s beginning to open up much larger issues and racial issues of course and climate change issues. It’s a great initiative.