Japanese Literature Sheds Light on Issues of Violence

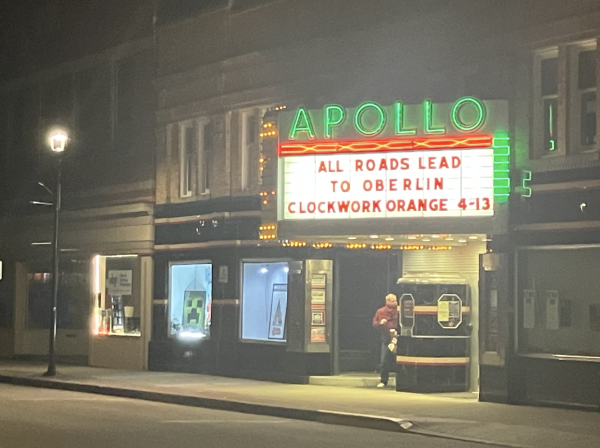

Scholars of Japanese literature convened in Oberlin last weekend for a conference on “Violence, Justice, & Honor in Japan’s Literary Cultures.”

The two-day annual conference of the Association for Japanese Literary Studies was themed “Violence, Justice, & Honor in Japan’s Literary Cultures” this year. Panel topics ranged from written Japanese literature, manga comics, gaming, and photography, among various other forms of visual art, all revolving around the theme of violence. “Minds are brutal places,” said Norma Fields, University of Chicago Robert S. Ingersoll Distinguished Service Professor in Japanese Studies and East Asian Languages and Civilizations.

The conference was hosted by East Asian Studies Professor Ann Sherif on behalf of Oberlin College. Normally held at research universities such as Yale and Penn State, the Association of Japanese Literary Studies conference took place at a liberal arts college for one of the few times in its 26 year history.

“Scholars came from as far away as Japan, Hawaii, and Italy because we crave the opportunity to dive in deeply with other researchers in our field,” Sherif said. “When I’ve attended it before, very few undergraduates came, because mostly this conference is hosted at research universities. … It’s usually just graduate students and scholars in the field.”

Perhaps for this reason, Sherif’s students made up the bulk of College attendance, even though the conference was widely publicized on campus.

“This is a great chance for the students who were able to participate to learn both something about the theme of violence, about scholarly method in the humanities … and how scholars network and do our work together as a community,” Sherif said.

In one session, “Proletarian Responses to Class Violence,” Bard College Assistant Professor of Japanese Mika Endo — joined by colleague Nathan Shockey and DePaul University Professor Heather Bowen-Struyk — spoke about the Proletarian Movement and the portrayal of violence in children’s literature, particularly that of working class families in the 1920s and ’30s. Endo mentioned literary pieces like Twenty-Four Eyes by Sakae Tsuboi, which describes the experiences of children watching their parents getting arrested and witnessing their pain, emphasizing the role these pieces have played in creating more emotionally sensitive children. She also mentioned her work on a compositional pedagogy called “Tsuzurikata,” or “writing education,” which encouraged children to write about their daily life in war-torn Japan, acting not only as a means of documentation of their suffering, but also as a kind of catharsis from the trauma of violence.

“The ethos of this writing education that I work on is that writing makes you look deeper and makes you pay attention to what’s going on around you,” Endo said. “That’s the ideal process by which writing is used to help improve your life.”

In an argument relevant to the United States, Bowen-Struyk alluded to different kinds of violence, particularly the slow and invisible nature of violence in capitalism. She mentioned highly troubling ideas such as workplace violence that can take the form of bullying or harassment, and their roots in the capitalist hunger for productivity, violence enabled by imperialist supremacy, and the violence wrought by poverty. Bowen-Struyk argued that poverty is essential for capitalism, since capitalism is dependent on the desperation of the poor.

“I think the problem is, if you don’t have … security nets then you — no matter how qualified and awesome — are willing to work for less,” Bowen-Struyk said. “Why? Because you need it. The more desperate you become, the less you’re willing to work for. And there’s nothing to prevent you from working for less than you could need to buy the food to replenish [yourself].”

Bowen-Struyk highlighted flaws in the capitalist economic model, which she said uses the vulnerability of the poor for cheap labor — significantly diminishing their standard of living — and then blames them for their inability to improve their conditions.

“Fundamentally in America, even though we talk really positively about capitalism, we have decided capitalism does need rules, and that’s why we do have a minimum wage,” she said. “What remains then, is this fiction that the system is fair but minimum wage still doesn’t provide a living wage. So you could work two jobs and still not have enough to pay the bills.”

In light of recent mass-shootings in the U.S., dealing with violence and its aftershocks is a highly pertinent topic that has grown in the national discourse. The representation of proletarian protest and their responses to violence using art resonates especially with the views of many Oberlin students who often unite on issues of social welfare.

“The arts in Japan have protested violence; they’ve helped people heal; some writers and artists have also aestheticized violence and promoted war,” Sherif said. “[The conference showcases] the ability of the arts to engage with many pressing issues today: nuclear weapons, nuclear tech, slow violence of environmental pollution, war, [and] virtual violence. … Even though Japan and the arts might seem distant, we’re grappling with really pressing social issues, and are highlighting the crucial role of arts in our society.”