From the Bass to Baseball: Perfecting the Right Pitch

Most Oberlin students arrive on campus at age 17 or 18, but Ian Ashby — first-year Conservatory student — familiarized himself with the College when he was 12 years old. He played baseball competitively in his hometown of Pittsburgh, PA until he was in seventh grade, when his father accepted a position as a Jazz arranging professor in the Conservatory and his family moved to Oberlin.

Every Wednesday, 12-year-old Ashby would practice his pitch on the red dirt of the old Dill Field while his dad, Jay Ashby, would teach a class. Dill Field has since been renovated — the classic dirt was switched out for a sleek turf diamond — but nowadays when he steps on the mound, he does so as an Oberlin varsity athlete.

A younger Ashby would cement his form and perfect his balance, and he would hear the stoic voice of a coach who would become his mentor all the way to college. Coach Abrahamowicz, who coaches varsity baseball here at Oberlin College and also assists with the Lake Erie Warhawks — a local travel baseball organization — recognized Ashby’s talent and has been working with him since he was in middle school.

The hours Ashby spent playing baseball during the day were complemented by nights full of jazz. Ray Brown followed Jose Ramirez. I can almost picture Ashby’s childhood: a scenic night full of MLB: The Show on the PS2, and Monday Night Baseball as Ashby walks around gripping an original iPod touch with headphones permanently in his ears. At the end of the night his eyes are fixed intently on the screen of a game, with his bass in his hands as he casually strums the strings and rapidly taps the fingerboard.

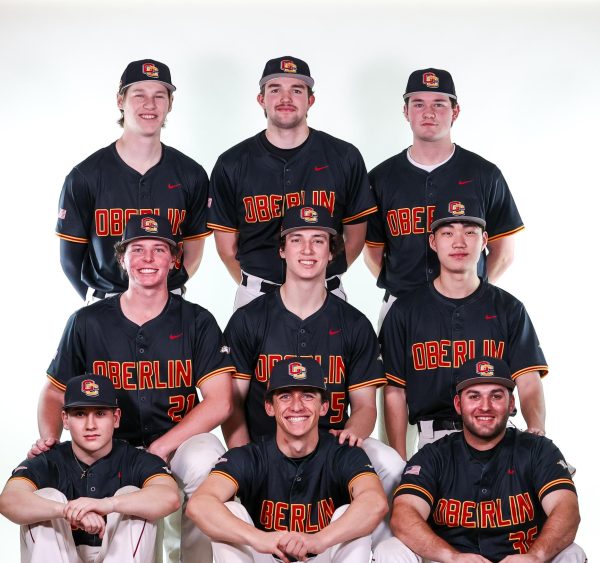

There are over 400 athletes at Oberlin, but what makes Ashby unique is his passion for athletics — adjacent and equal to his passion for music. He has a fidelity to both, committed as a full-time varsity athlete and a Conservatory student. The grueling practice hours of baseball alone are daunting, and Ashby adds a rigorous Conservatory curriculum and practice schedule to them.

When I sat down with Ashby, he briefly explained his schedule: a morning workout followed by a quick practice session for bass, then class all day, baseball practice, and bass practice again. Each day Ashby allots three hours to practicing both jazz and baseball. Most people wonder how he manages to do both, but I wanted to know why he chooses to do both.

When I met with Ashby, he was repping a backwards Oberlin cap and a hoodie with a large “O” and “C” on it. He didn’t drink coffee or even look at the Slow Train menu. Trying to get a gist of how intense and elite Division III baseball is, I alluded to my own athletic endeavors — mediocre at the high school level — during which Ashby politely nodded, and then proceeded to relay details from the workouts he and his teammates have to endure daily.

Needless to say, I regretted saying what I bench pressed before Ashby told me what he does. Varsity is no joke. The average athlete might feel physically drained after going to the gym once a day for an hour or two, but Ashby has to spend almost three hours per day focusing and exerting himself. Anyone who has been on a sports team knows that practices and games aren’t just physically draining, they’re emotionally draining and stressful as well. Exhausted, most people would be entitled to rest post-practice — but for Ashby, this is when he starts to play the bass.

Ashby posited that there is a tendency to separate activities like music — which appear intensely cognitive — and athletics — which appear purely physical. This tendency is, unfortunately, a result of both sides failing to fully comprehend the similarities between the two. Music and athletics are both about getting lost in the focus they require.

“For both music and baseball, it’s really an escape,” Ashby said. “And I don’t want to sound basic, but that’s really what it is. It’s a place you can go and get lost.”

Extreme focus has this effect. Whether you like to sing, drive, write, run — whatever your passion — we choose some activities because they require our attention. Going for a drive might be a cliché, but the road forces the driver to focus. When you combine experience with focus, the result catalyzes a kind of meditative state. Ashby “goes for a drive” when he’s on the mound on Dill Field eyeing the catcher, or when he’s holding his bass in Warner Concert Hall at the Conservatory.

“But why do you work so hard?” I asked. “What is special about the kind of focus that you get from both baseball and jazz?”

Here’s what it is: “When you see old-time jazz players, and they’re constantly having a conversation beyond words, and they’re having moments with each other — real moments where they’ll tip their hat or wink or do something to acknowledge the moment they just had — that’s what everyone in the Conservatory, including me, is working for. It’s similar for baseball — there’s that moment when you connect with a teammate on a play and in an instant, the waiting is over.”

Ashby doesn’t participate in baseball and music for glorification or validation. At its core, it’s not just for escape. In his mind, jazz and baseball are not just analogous, they’re the same. Although baseball is more “slow-paced” and jazz has a “constant response rate,” the moment when he connects to others is the same in both.