Art Exhibition “Counternarratives” Sparks Conversation on Campus

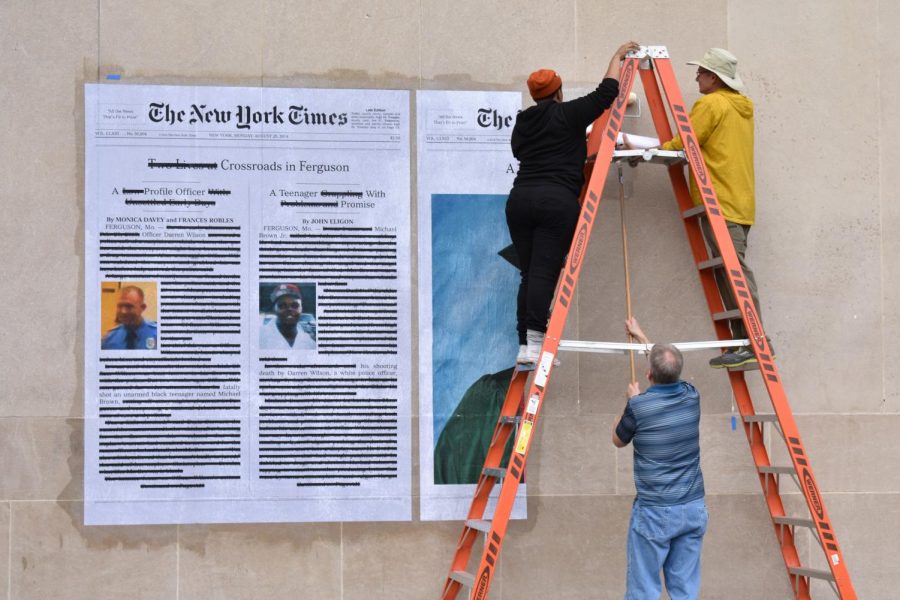

Alexandra Bell and others install “A Teenager with Promise” outside Mudd library on Tuesday, Oct. 30. The work critiques major media coverage of the 2014 fatal shooting of Michael Brown.

Students walking past Mudd library or the Allen Memorial Art Museum this week may have noticed enlarged markups of The New York Times front pages posted on the buildings’ facades. These works, installed this week by Brooklyn-based artist Alexandra Bell, are meant to showcase the consequences of how news is portrayed by major news and media outlets.

“I first encountered Alexandra Bell’s work on Instagram over a year ago, as I was starting my position at Oberlin,” said Allen Memorial Art Museum Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Andrea Gyorody. “I found her work to be both timely and poignant, and immediately began thinking of ways that her work could appear on campus.”

Bell introduced Oberlin to her Counternarratives project last Monday in a lecture in Hallock Auditorium, which focused on how issues around race and violence are reported in the media. Bell, who holds a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University, confronts the problematic notion of holding media to be an absolute “truth.” Counternarratives utilizes walls in public locations to mount redacted, annotated, and edited newspaper clippings, alongside versions she creates that provide a different truth and perspective.

“Is there a way something can be factual, but not completely true?” Bell asked the audience during the lecture.

Oberlin is the site of two of Bell’s Counternarratives pieces — the one located at Mudd critiques media coverage of the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in 2014, while the other, posted at the Allen, evaluates journalistic shortfalls around coverage of the violent far-right protests that erupted in Charlottesville, VA, last year.

Bell’s artistic process begins with transferring articles that appeared in the print version of The New York Times — the artist is a self-proclaimed “news snob” — into Adobe InDesign. In doing so, Bell hopes to glean a more thorough understanding of the article’s content, as well as replicate the arduous process of creating and consuming print media. From there, she annotates the articles, examining their role in perpetuating dominant narratives.

One facet of media coverage that Bell explores in her work is what she called “the placement of whiteness.” Whiteness is often afforded invisibility — meaning it is uncommon that white people are described by their race — when all other races and ethnicities are almost always pointed out.

Bell often critiques the way information is presented by major news outlets. For example, in the piece on Michael Brown, Bell examines why Michael Brown and Officer Darren Wilson were, in their side-by-side profiling by The New York Times, given a false equivalency. She questioned various facets of the coverage of the fatal shooting, asking why Wilson’s profile — when reading from left to right — is first. Furthermore, Bell tackles the issue of how Black males are often demonized in the news. These portrayals of an entire demographic of people have allowed for discriminatory policies and court rulings that have made Black males five times more likely to be incarcerated than their white counterparts.

Historically, Bell argued, Black people were not allowed to participate in the creation of news narratives — through, for example, objective interviews — but rather, were discussed as chattel. The journalistically-trained artist cross-referenced an article from the 1830s discussing the sale of slaves with more contemporary pieces.

“You can see the reverberation of this animalistic language [today],” Bell stated, referring to the historical use of words such as “demon” or “brute” to describe Black people in the media.

For the Michael Brown piece, entitled “A Teenager with Promise,” Bell replaced the side-by-side profiles and grainy photos of both subjects with a large-scale image of Brown’s graduation photo, with the titular phrase serving as the headline. According to the artist, this was an intentional move to highlight Brown’s age and innocence. Bell said that the ages of Black males are often ignored by the media, in favor of reports of previous criminal acts or negative personality traits. For example, The New York Times infamously referred to Michael Brown as “no angel.”

“The media [doesn’t] see them as kids,” College senior Hanne Williams-Baron, who attended Bell’s talk, said. “[They] always talk about [Black males] smoking weed or selling drugs, and this takes away their innocence.”

One aspect of printed news that Bell introduced was the significance of being “above the fold.” When the newspaper is folded, the reader only sees the images and headlines above the fold — thus, the layout of print media has exceptional power to define or perpetuate a certain narrative.

Bell’s piece entitled “Charlottesville” depicted the transformation of the headline of The New York Times article by minimizing the original large photo of a young couple and enlarging a poignant photo of the car that rammed into the protestors.

Bell also tackled the importance of layout with her other work “Olympic Threat,” which focused on The New York Times article “Accused of Fabricating Robbery, Swimmers Fuel Tension in Brazil,” which instead of using a photo of the white swimmers used the photo of famed sprinter Usain Bolt, attatched to another article on the page. This allowed for a word-image association between robbery and male Blackness to occur.

“You [can’t] put a headline like that and put a black man there,” College sophomore Ivy Miller said. “People need to watch and think about what they are doing.”

Bell has begun to transition away from Counternarratives. She is currently working on a non-public artistic project that focuses on media coverage of the “Central Park Five.” In 1990, five Black teenagers were wrongly convicted of raping a white woman in Central Park the year prior. There were 28 other assaults that week — two of them on white women, two on Asian women, and 24 on Black and Latina women — yet, according to Bell, print media was utterly captivated by the case in Central Park.

In this endeavor, Bell hopes to evaluate how people with social capital and money “get the top billing” in the media. For example, during the time of the attacks, Donald Trump paid $85,000 to take out a full-page advertisement calling for the death penalty.

Bell’s captivating lecture left the students in attendance with a new analytical lens, one that challenges the “dominant narrative.”

“[I am more] aware of potential biases of journalism in the news,” Miller said.

When it comes to a news publication like The New York Times it’s important to recognize its audience — largely composed of upper-class educated people. Ultimately, Bell’s lecture and art presented an opportunity for students and community members to ruminate on the responsibility of major print publications to provide objective news for all people, not just the people who have historically consumed the news.

“Above all else, I knew that [Bell]’s work, being publicly sited on campus, would spark conversations and debate in a way that objects in the museum sometimes fail to do,” Gyorody said. “I trusted that the entire campus community would benefit from the presence of her work, and from her talk and lunch with students.”