Experimental Arts Films Screened in Conjunction with AIDS Talk

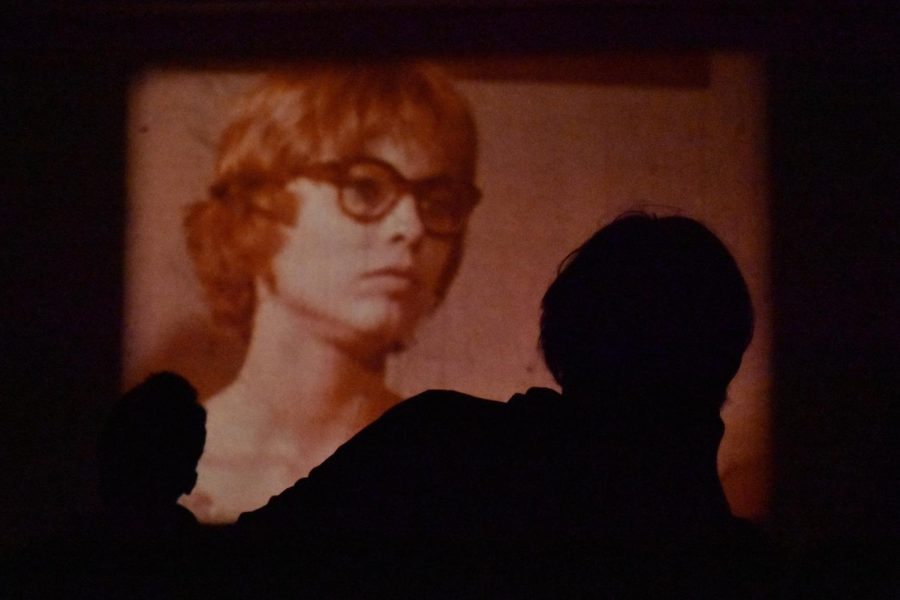

A still from one of filmmaker Luther Price’s short films, screened Tuesday in the Clarence Ward ’37 Art Building.

What do surgery footage, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, hardcore pornography, and paint have in common? Visiting Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History

James Hansen ran all of them through his personal Super 8mm film projector on Tuesday in a presentation of seven original films by Boston artist Luther Price. This coincided with a Convocation address by Jesse Milan Jr., the president and CEO of AIDS United.

Price, an interdisciplinary experimental artist with a rich body of work on film, lent Hansen the films pro bono. The seven short films consisted of free-association mashups of footage, some shot by Price himself and others ripped from various sources. Footage of dated Hollywood melodramas, cowboy Westerns, operating rooms, and men performing various sex acts conversed with each other.

“The screening … totally surpassed all my expectations,” said College senior Alex Scheitinger. Praising the “intimate setting” of the screening, he commented, “We were all intently focused on what was going on on-screen.”

It’s true — during the first screening of a three-minute long, completely silent film called House, you could’ve heard a pin drop. The film interspersed mildly disorienting footage of a quiet semi-urban landscape, branches, siding, windows, and sunsets, with explicit footage of two men in a nondescript room having sex. The film’s program notes suggested that House is meant to resist the way queer sexuality is relegated to the private domain, out of the public eye. As Hansen put it, “The suggestion is that gay sex is happening there [behind closed doors] and that’s something you should see.”

Hansen discussed the way Price’s work, during the time of the AIDS crisis, came into conflict with certain tendencies among activists for queer visibility and acceptance.

“The objective in the gay community at the time was to have positive, affirmative images of gay people — which often meant that you’re not showing gay sex,” he said.

Tuesday’s screening demonstrated a healthy and necessary response to the idea that homosexuality is shameful and should be hidden to gain social acceptance.

In a 2012 interview with Tara Nelson, another Boston-based filmmaker and curator, Price rejected being pigeonholed “as this gritty, badass, gay filmmaker [that] I’m not.” Nevertheless, his use of raw pornographic footage sets him apart from many of his avant-garde film predecessors and contemporaries. As Hansen noted, avant-garde filmmakers have long incorporated pornography into their work, but few have refrained from “working over, or shifting that material,” making pornography an instrument for other political or aesthetic aims. In contrast, in much of Price’s work, “it’s still pornography.”

This is not the first time Hansen, who has known Price since 2012 and published scholarly works such as “The Fall of Days: Luther Price’s Nine Biscuits (2004-08)” about him, has shown Price’s films at Oberlin. In spring 2018, Hansen screened six of Price’s 16mm films. Tuesday’s screening showcased Price’s Super 8mm films, a format that is comparatively smaller, cheaper, and allows for less clarity and detail, making it less “professional.”

Additionally, Super 8 is a considerably fragile format, which is easily scratched and worn. Price utilizes this feature to physically scratch lines into the images. Part of what makes these films unique, and according to Hansen, “one of the reasons [Price] has been taken up in the art world more recently,” is because the original films themselves are art objects.

For example, the final film shown, Gift Givers, consists of found pornographic footage which Price then physically painted on top of, creating a beautiful, distinct visual effect. This technique means that paint will inevitably scrape off the reel when the film is projected. In a 2012 interview with Idiom, Price lamented that his films have accrued a reputation as “unprojectable.”

While this characterization of Price’s films might be a bit overblown, Hansen confirmed that Gift Givers did, in fact, get his projector “really dirty.”

Though the Anthology Film Archive in New York has taken on the project of digitizing some of Price’s films, their quaint, hand-assembled charm and the aura of physical objecthood can’t be reproduced. For this reason it’s a major privilege to see them — according to Hansen — “struggle through the projector.”