Kat Burdine, Visual Artist

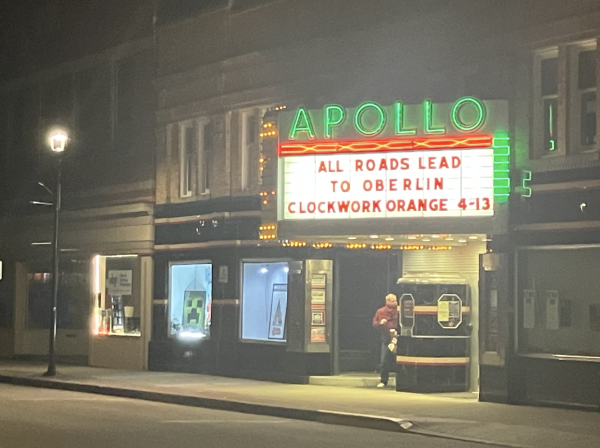

Kat Burdine speaking to Oberlin students last Monday.

Artist Kat Burdine uses objects and prints to negotiate ideas about physicality and the body. A graduate of the Cranbrook Academy of Art and currently based in Cleveland, she is the founder of Wondershop Studio and teaches at both the Cleveland Institute of Art and Cuyahoga Community College. She has collaborated with many artists on a variety of projects, including Talking Dolls in Detroit. Her recent lecture at Oberlin, “A Matter of Hapticstance — One Queer’s Feeling on Feeling(s),” discussed “the possibility of engaging within the space we lose when our understanding of self, relationship, and community is controlled by language.” She will be back later this semester to work in the Reproducible Print Media Lab.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I’m aware of the irony of interviewing you after part of your lecture was about the limitations of language, so I’m just curious if you could tell me a bit about what you feel you’re able to articulate through your art that doesn’t necessarily have the same impact in words.

I tend to work fairly physically. I have a relationship with my materials — I respond a lot to how they feel in my hands. So I think that from the beginning, the conversation I’m having with the work and the material is pretty physical. But I also think that in physical spaces, some of what I’m interested in talking about is slippage — and maybe I’m not a wordsmith, in that there are people I know who use language in very beautiful ways that can hold all of that slippage of meaning. I’m not that person, fortunately and unfortunately, so I think that if I can open up spaces where there’s possible slippage, there’s possible disarming in that. Because language can be so precise — which at times is very important, but I prefer the openness of the body and the things that, when we’re paying attention to our bodies, the body tells us.

In regard to empathy and understanding, we are smart creatures, so we often jump to conclusions and assume for various reasons. I think if our bodies interact with material or site-specific work or whatever it is, if our bodies interpret it and it takes us another beat to make a connection, what happens in that space? What are we opening up? Are we opening up the ability to empathize with another experience or feel a certain kind of silliness that we don’t allow ourselves in our daily performance? Or are we able to feel uncomfortable, in a way that our ways of carrying ourselves in the world don’t allow? So hopefully in that way it’s opening these new spaces in which to be sensitive to our bodies and to other people.

I think that normative bodies often don’t feel as out-of-place as non-normative bodies. People who fit in, in whatever ways they apply convention, are less aware of the type of space their bodies take up. On the other hand, not only are we working on that openness that can make people sensitive to their bodies and more aware of that — and everybody has their own baggage with bodies — but the way that normative bodies get to exist in the world. If I can bring some of that other awareness into a room, then it also breaks down different conceptions of space and allows us to have different sorts of openness.

What made you interested in creating installations that promote audiences’ physical engagement, and how have you approached doing that?

I think I’ve always been interested in the idea of body awareness. The idea of installation felt like a pretty easy way to start thinking about tapping into body awareness. I think scale starts to make us reassess our size against other things and make us a little uncomfortable, since the world is designed to fit our scale. So I think that installation is kind of an easy access point. I am very sensitive to space and I’m sensitive to how space is activated, but I’m not necessarily having installation conversations that are architectural. I’m using installation in a very specific way, and I don’t usually use that word to describe my work. I’m more interested in spatial intervention, because I think, again, what I’m trying to tap into is activation. I’ve never done anything where I transform space; it’s more like an intervention in that space that allows our bodies to think about the way we take up space. And I’m still figuring it out!

How do you distinguish between the contexts of gallery or non-gallery spaces, and how does that inform what you do?

They carry a different set of complications or contexts — they’re weighted very differently. I’m entering into a conversation that the gallery has established or that the space has established. In a lot of ways I’m working against convention, or I’m working against some of the notions of how that space is already charged. But collaboration is part of the way I exist, so if there are histories in a space I’ll often work with those too, because we all carry those with us. But in non-traditional spaces I feel like I can play in a different way or I can be more improvisational with the audience because there’s much more room for the unexpected. So in the dance party performance that I mentioned in the lecture, some of what was really exciting was that I love dancing — I don’t know that I’m any good at it — but on the dance floor your whole body’s engaged. You get to improvise with this community around you — in whatever way that you feel comfortable but also as defined by the dance floor. There’s already this exciting set of social rules. So I feel like I get to play in that space differently, because there’s less weight on the other person. You get to play in a totally different way.

I wanted to talk on Monday about how to build your own world map in this wildness — because if I’m talking about less-articulated spaces, it’s a really easy place to get lost in. For me, things like improv are really nice ways to set up protocols that indicate how I behave in wilderness or open spaces. It’s not scary if I go in and say, “All I need to do is respond in a way that’s respectful to the people I’m responding to and add to the situation.” And if those are my rules, then there’s no fear behind that. If people are engaging together, all you’re doing is building something together.

When you were telling us about the work you did with flannels, you talked about signifiers and symbols in your work. I’m curious if there have been other times when you’ve chosen to tap into recognizable signifiers in your work.

Often I default to athletic equipment, specifically baseball. I’ve played a lot of sports, but baseball holds this really strange place in American nostalgia that allows me to think specifically about my experience, but also larger contexts. Baseball has a specific meaning that starts to unlock sensory and contextual memories, and so I’ve used my experience in that and started queering bats and gloves and undoing their function to create a new space that still exists and references that initial impulse.

I also grew up on a block that was like a silly Norman Rockwell painting — there were like 13 boys and me. So we played ditch every night, and we played quarters, and we invented all these games. Through game and play and proving yourself, or your toughness, we were establishing these momentary hierarchies of who was the toughest. Everyone else at the table thinks it’s one moment and then kind of arbitrarily your whole personhood depends on winning that moment. There’s always this construction of identity and how it exists — thinking, “Oh, I really need to do something here to make sure people see me as valuable.”

In your PowerPoint, you listed sources at the end, but on the slides you also listed materials or inspirations you’d interacted with that informed a piece. How do both personal and academic research interests work as sources for your artistic practices?

The footnotes are something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, whether the appropriate form is footnotes or not. But I’ve noticed that there are times when we go to academic talks where we still reiterate the independent genius of the artist. I could not exist without the communities I’ve been able to build or those who were invested in me, and I’m trying to practice different ways of acknowledging that I can only exist within the context of those who exist around me. I was really trying to confront the importance of relationship, relational building, communal knowledge, and informal transfer. We have bibliographies as these very formal ways to acknowledge people we’re referencing.

With my footnotes, I was trying to reference the generosity not only of the authors I’m reading but also of the people in my community who’ve taken time to feed back in — and hopefully I’ve been able to reciprocate. How do you start networking in different formats? How do you start referencing the informal spaces of critique and research that are not part of a system of academia or privilege or other sorts of [exclusive] systems? I’m trying to figure out how to tap into the relational importance of the amount of learning we do socially, and all of these layered networks we feed into with our ideas. Part of my initial effort is just acknowledging that those networks exist, because I’ve seen people erase those by not acknowledging that they’re learning together.

I’m now writing a lecture that has no formal messaging; it’s all footnotes-based. How can I spend an hour reading work that both makes sense and doesn’t make sense but is a necessary tool for context?

I understand that you’ll be back to work at Oberlin on a project this semester. Do you have any idea what that will look like?

Sort of! [Associate Professor of Studio Art and Reproducible Media] Kristina Paabus is amazing, and I’ve been super excited to get to know her better and see the department that she’s building and the dialogue that’s going on. It’s been exciting to figure out how to enter into the conversation that they’re having. I don’t want to come in and say, “This is what I want to do.” So we talked and went out to dinner, and I asked the two students who will be helping me what they’re interested in. Because I’m interested in slippage and because I have two or three modes of production that carry content, I’m trying to figure out how to fit into that dialogue and make it more of a conversation. I’m trying to think of it how I think about everything: How do we take a traditional set of order of operations and where can we insert the fly in the soup? We can create an unexpected outcome that will undo itself or rebuild itself in ways that we could not do without going through the process together.