Student Organizations Shed Light on Oberlin Protest History with Powerful Projections

A visual history of Oberlin activism was projected onto the outside of Mudd Center last Thursday.

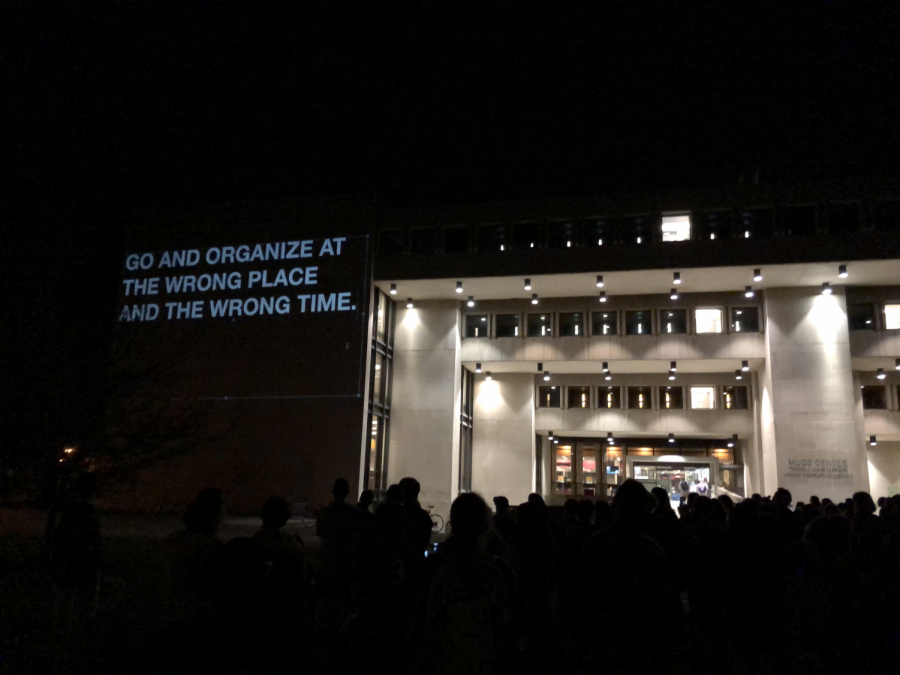

Last Thursday night, students and passersby might have noticed a series of protest messages and art projected onto Mudd Center’s East-facing wall. With the help of a 10,000-lumen projector and a generator, the library was shrouded in a spectacle of still images and moving frames depicting the history of student protest at Oberlin.

The projections — a collaboration between students in the classes Creative Interventions and From Bandung to Black Panthers: The Past, Present and Future of Third World Liberation — were part of a project meant to create an intervention in public space.

The public protest was associated with with the Illuminator collective as well as student groups: Jewish Voice for Peace, Students for Energy Justice, Students for a Free Palestine, and Student Labor Action Coalition.

“I’ve been involved in interventionist art for a decade and this is one of the most moving examples of this kind of public art I’ve ever seen,” said Grayson Earle, visiting professor of Studio Art and Integrated Media.

The images on Mudd Center showed quotes and images from Oberlin’s history of activism. College seniors Nicki Kattoura, Emma Doyle, Lara Edwards, and Octavia Bürgel, the event organizers, told the Review in a collective statement it was “student labor [and] action disruption that actually put the College on the right side of history, and … those movements were almost always met with administrative push-back. The history of Oberlin’s activism was paralleled with current student demands and protests.”

This project is meant to remind students of the school’s history of critical engagement and to encourage them to carry this legacy into the future.

“The students also projected their own words in response to the administration who have asked students not to protest at the ‘wrong place at the wrong time,’” Earle pointed out.

The collective response from student groups declared this list of student demands: “[to divest] from Israel, to boycott Sabra products, to provide students [with] resources to protest the Nexus pipeline, and to recognize the importance of unions and workers on this campus.”

Some students on campus thought the event was sponsored by the administration when in actuality it was an anti-institutional demonstration. In the Oberlin Facebook group “Oberlin Consortium of Memes for Discourse-Ready Teens,” College first-year Michael Plevin made a poll asking for student opinions on the projections. There was debate and confusion as to who was behind the projections and what the overarching purpose was. Some students first assumed that the College was behind the light show.

“My first reaction was mixed,” Plevin wrote in an email to the Review. “But it seems a bit disingenuous to me in that, so far as I can tell, it seems like [the College is] doing it to try and woo the prospies.” Plevin continued to discuss student reactions to the spectacle.

“[Responses to the meme] show how many people are confused about the College’s spending and are upset or exasperated with what they choose to spend their money on,” he wrote.

The Illuminator collective, a New York City organization that offered their time and equipment, formed out of the social networks of solidarity and trust from the Occupy Wall Street movement. The group was financed by a $60,000 grant by Ben Cohen of Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream. His business partner, Jerry Greenfield, graduated from Oberlin in 1973. The Illuminator collective outfitted a van with a powerful projector and generator, using it for smaller display pieces on topics like Edward Snowden’s NSA leaks, the Guerilla Girls movement, and Trump’s Muslim travel ban. Today, they work with various large and small organizations and operate on a sliding scale cost model based on their clients’ financial status. Organization representatives Emily Allyn Anderson and Kyle Depew spoke at an informational panel on Friday at the Ward Art Building.

“One great strength of radical politics is the affinity group — that tight network of trust,” Anderson said. “When you begin operating in these realms that are illegal and challenging to the dominant power systems, there are a lot of ways that things become dangerous. We’ve built a network of trust that can be used to do many things, but projection is the dominant mode of expression we use.”

“I think it’s fascinating in New York City because it’s an environment that is so inescapably encased in advertisements,” Depew said at the panel. “There’s so much visual imagery in that place that I like playing with and taking it back. We see a blank wall as the peoples’, even if it’s just for 10 minutes.”

Anderson spoke about the potential risks in projecting images onto public and private buildings.

“Doing this in New York City is stressful,” she said. “We are always on the lookout for police, or people who are upset at what we are doing. On the day of the Trump inauguration, we had multiple people screaming at us and grabbing the projector. Nobody’s ever been assaulted doing this, though cops are a big thing too. We often get shut down by the NYPD. We get asked to move along. Now we try and project something as long as possible.”

“We start speaking to the cops, saying ‘Oh, it’s a student project’ and try to buy more time and delay them,” added Depew. “There are ways around authority.”

The student organizers added that it was incredibly inspiring to work with the Illuminator Collective and engage with an audience in such an innovative way.

“It was exciting to see our message be projected on the wall and to be able to share it with such an engaged audience,” the student organizers wrote. “We got word that students joined the organizations after seeing our projections, and that is the biggest success of the event.”