Slavery’s Modern-Day Impact Felt in “Afterlives of the Black Atlantic”

Left: “Black History, Nighttime”. Right: “Church in Oberlin, Ohio” 2 pieces by William E. Smith, an American arist, in 1971.

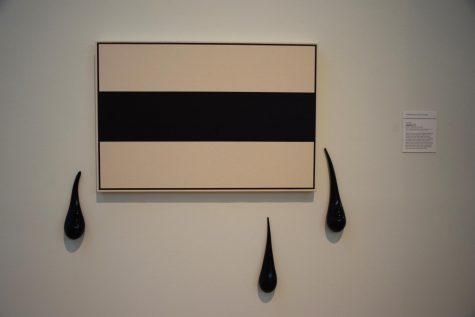

“Liberation” created by Fred Wilson, an American artist, in 2012.

“Bocio,” unrecorded artist from the Republic of Benin or Togo in the 20th century.

Left: “Valicia Bathes in Sunday Clothes” by Vik Muniz, a Brazilian artist, in 1996. Right: “Ethiopia” by Rev. Albert Wagner, an American, in the late 20th century.

“Afterlives of the Black Atlantic,” the Allen Memorial Art Museum’s latest exhibit, seeks to redefine the written history of slavery. The show commemorates the 400th anniversary of when African slaves on the English warship White Lion landed at Point Comfort in the Colony of Virginia on August 20, 1619. This date marks the 400 years since the beginning of institutional slavery. Curated by Assistant Professor of Art History Matthew Rarey and the Allen’s Ellen Johnson ’33 Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Dr. Andrea Gyorody, the exhibition will be on display at the museum until May 2020.

The exhibit argues that slavery is neither geographically exclusive nor exclusive to the past. By bringing together pieces from the United States, Europe, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa, the exhibition addresses issues that persist today as a result of slavery — issues such as human trafficking, cultural exchange, struggles with identity and belonging, and collective trauma. “Afterlives” gives voice to contemporary artists and their relationship with slavery’s legacy.

For Rarey, an art historian specializing in Black Atlantic art and visual culture, “Afterlives” is an extension of his regular work at Oberlin. His classes and the exhibition seek to preserve and uphold world cultures that are overlooked by modern society. As a curator who also works in academia, Gyorody has experience in the classroom and also engages with the general public.

In fall 2016, after discussing the upcoming 400th anniversary of institutional slavery with Professor Mindy Fullilove at the New School in New York City, Rarey and Gyorody decided to commemorate the anniversary with a show. Work on the exhibition began in 2017 and was completed after two and a half years.

The exhibition focuses on unmooring of traditional narratives to create a conversation between the past and present. “Afterlives” seeks to “commemorate, not celebrate, that history, but also interrogate it a bit because those were not the first enslaved people to arrive in the United States,” Rarey explained. With the exhibition, Gyorody and Rarey wanted to address the complexities of slavery’s history and present the diversity within the African continent.

“Africa is not one place,” Rarey said. “It has 54 countries, it has thousands of languages and cultures, and it has a very long history of interactions inside of it and outside of it … that has had as strong a role to play in the formation of what we call the modern world as any other place.”

In addition, Gyorody described how the Ellen Johnson Gallery’s shape enhances the viewing experience. The open floor plan allows viewers to take in nearly all the works simultaneously, allowing them to exist in conversation with each other, unmoored from historical and geographical barriers.

“As you’re walking around the gallery, you’re compelled to start thinking about not just discrete objects but how they link up with one another, which is entirely what we had hoped for,” Gyorody added.

One piece by New York-based artist José Rodríguez, titled “\sə-kər\” is available for public viewing starting today at 5:30 p.m.

“I chose the phonetic spelling because it alludes to that space between and can be read as both ‘sucker’ and ‘succor,’” Rodríguez explained.

A former classmate of Rarey’s at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Rodríguez was commissioned to create a piece specific to the exhibition. The object, a twelve-foot high, teepee-shaped structure that viewers can physically enter, is part of Rodríguez’s effort to create art that demands interaction and reflection from the viewer, not just passive observation.

In “\sə-kər\”, Rodríguez depicts the Cuban iteration of the Virgin Mary, “la Virgen de la Caridad,” with a mirror as her face, challenging the viewer to reflect upon their relationship to divinity and what divinity represents. The way that the Virgin Mary’s face changes depending on the viewer adds dynamism and impermanence to visual art, an otherwise static medium. Rodríguez seeks to capture the “ephemeral” nature, as he describes it, of mediums like dance or spoken poetry, and challenge viewers’ ideas of art itself. He encourages viewers to look deeper at both the art and slavery’s surface-level historical narrative — neither are static or isolated in the past, instead both are actively shaped by the viewer.

While the outside of the piece depicts images from European Catholicism, the inside imagery is dominated by aesthetics from African cultures and religions. The structure itself juxtaposes European and African imagery to visually represent how colonialism obscured African cultures and religions from an outside gaze.

Above all, Rodríguez wanted to highlight the interconnectedness of different people in American history. He emphasized that slavery does not begin and end with the United States, citing his family’s experiences with slavery in Cuba after it was abolished in America.

“When we talk about black history or Latin history, we’re really talking about American history, and it belongs to all of us,” he said. “And I think we have to learn to appreciate each other’s stories in that way, because it’s all of our stories together.”

Most importantly, the majority of the show’s pieces are abstract, taking on non-human and unfocused forms. Rarey explained that these abstract renderings consciously stray away from the graphic, shocking depictions of slavery that are usually presented in history textbooks and archival material. Pieces that are more literal in their presentation of violence are usually meant to sensationalize the horrors of slavery, while imparting the false message that these horrors are long over and no longer affect modern society because these images do not exist in a modern context. Rarey states that these pieces collectively create a somber, reflective mood that still effectively conveys the diasporic and emotional damage that slavery has left on the world.

“It’s really necessary and urgent because it seems like there are certain lessons from the past that we still haven’t learned,” Gyorody said.

“For a lot of people, [slavery] isn’t a distant memory. This isn’t the deep past. This is, in the United States, less than 150 years ago,” she added. “The fact that [contemporary artists] are contending with the legacy of slavery says to me it’s still relevant today.”

“Afterlives of the Black Atlantic” will be displayed at the AMAM through May 2020. Additionally, smaller pieces will be switched out with new art pieces at the start of the spring 2020 semester.

Students are welcome to visit the Allen and learn more about slavery’s lingering impact on world history and society. At 5:30 p.m. today, artist José Rodríguez will be unveiling and speaking to the public at the Allen about his commissioned piece.