Cartoonist Eli Valley Discusses Jewish-American Identity

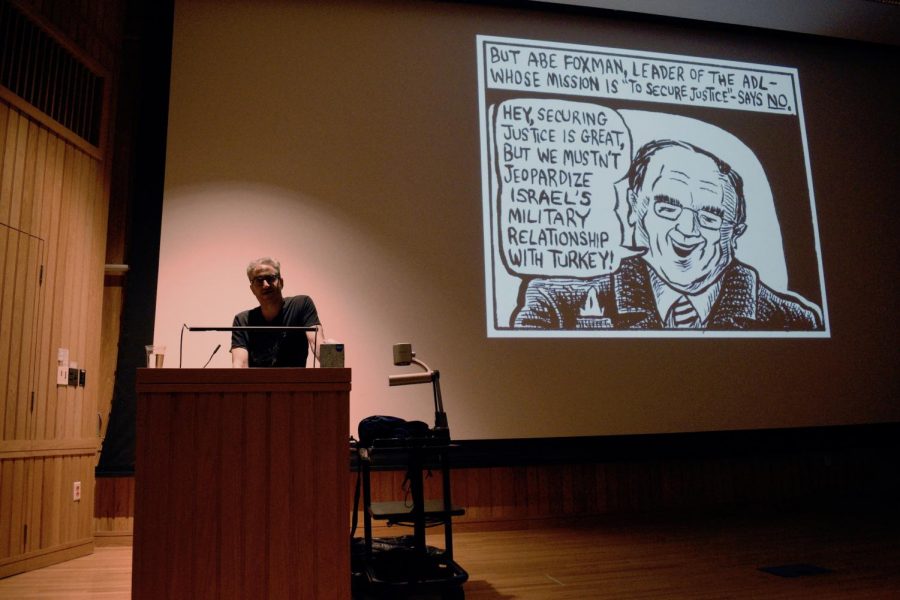

Eli Valley discussing his comics in Dye Lecture Hall.

When cartoonist and activist Eli Valley was young, he used to imagine superheroes and supervillains battling on the pages of the Hebrew Bible, the physical seam of the book serving as the divisive line between good and evil. Valley’s father was a Rabbi, and he says that comics initially provided him with a sense of escape from his Orthodox Jewish upbringing and countless hours spent in the synagogue.

Today, Valley is a well-respected cartoonist whose work has been featured in The Nation, The New Republic, The Village Voice, The Guardian, and The Daily Beast, among other publications. Oberlin Students for a Free Palestine and Oberlin Jewish Voice for Peace brought Valley to campus this Tuesday to give a talk on his work.

Valley’s cartoons highlight the complicated relationship between American Judaism and Israel. The cartoons sharply critique American Jews and non-Jewish politicians who ally themselves with neo-Nazis and white supremacists in their mutual support of Israel. His full-length comic book Diaspora Boy features the titular character — a grotesque old man who is constantly in need of help and advice from “Israel Man.” Israel Man is a Superman-like adonis who towers over Diaspora Boy and whose perfectly-coiffed hair, muscles, and smile sharply contrast with Diaspora Boy’s hairy, wart-covered body and sickly physique.

Valley is best known, though, for drawing similarly jarring caricatures of political figures like Donald Trump, Benjamin Netanyahu, Steve Bannon, and Fox News anchor Meghan McCain; they represent the paradigms, politics, and contradictions of American Jewry in the 21st century. Stylistically, he’s inspired by the aesthetic and cultural roots of American Jewish comic art and satirical criticism.

“Mad comics [were] made by children of immigrants, bringing a Yiddish sensibility, — both culturally but also, even linguistically — throwing Yiddish in everywhere,” Valley explained. “They were coming out during a time of American [consumerism and political and cultural] conformity, and so they were satirizing American popular culture, but at the same time really going for the jugular. And the art was just incredible. … That was my main source [of inspiration].”

College fourth-year and SFP Treasurer Matt Kinsella-Walsh thinks that Valley’s comics speak to the problematic tropes underpinning Zionism.

“He did a really good job on showing how much of Zionism is predicated on anti-Semitism [and] has continued to replicate tropes that are [actually] anti-Semitic to Jews that do not fit into this Israeli ideologized archetype,” Kinsella-Walsh said.

Zionism is the belief that there should be a secular Jewish nation state in historic Palestine. When the Zionist movement began in the 19th century, the settlers promoted the image of the “new Jew.” Whereas the diasporic Jew in the ghettos of Eastern Europe was emaciated, homely, and hunched over their religious scripture, the Zionist Jew was a fighter, hair bleached blond from hours working under the hot Mediterranean sun, and whose back straightened and shoulders broadened. These 19th-century ideas are still influential today — political leaders from both the United States and Israel, Jewish and non-Jewish, portray the diasporic Jew as lost, sickly, and pathetic, while the Israeli Jew is authentic, powerful, and attractive.

“The Jewish [political] right, and the right more broadly, have succeeded in altering the definition of anti-Semitism to [mean] anti-Israel, or to [mean] criticism of Israel even,” Valley explained. “And in so doing [the right is] actually trying to erase a large segment of American Jewry, [an act] which itself is anti-Semitic, but because they are represented in leadership positions within the Jewish community, there’s never sufficient pushback and so their line becomes the [official] line.”

College second-year and Liaison for JVP Mira Newman found that comics are a really successful way to conceptualize the difficult concepts addressed in Valley’s work.

“I think that it’s really cool that a lot of what he does– comics– are very accessible to a wide audience when a lot of things on Israel and Zionism, specifically anti-Zionism, [are] very theoretical and [inaccessible],” they said. “He puts it in these really easy terms. I think it really gives the opportunity for a lot of people to take what he says and actually understand why people think certain ways about anti-Zionism.”

Naturally, Valley’s work has received significant criticism and accusations of anti-Semitism. While Valley is not deterred by the critics, he still felt alarmed by the extreme criticism he received from high profile media outlets.

“When a Stanford law student calls me a Nazi and lies about my work, and then a New York Times Opinions editor amplifies that, that had actual ramifications that were extremely stressful,” he said.

However, Valley maintains that his work is significant to the American public. His comics may have shock value when they portray right-wing leaders, including the president, as grotesque or even monsters, but Valley hopes his leftist messaging can hit home in a way that doesn’t just poke more fun at the buffoonery.

“Hopefully it jolts people out of acquiescence to this slow but inexorable march to fascism,” he said. “I feel that it’s a more important contribution to expose the corruption and bigotry.”

Valley’s lecture kicked off a week of joint JVP and SFP programming, as the groups respond to ongoing violence in Palestine and invite contentious speake rs like Valley and political activist Norman Finkelstein. On Wednesday, the groups constructed an installation in Wilder Bowl, memorializing the murders of 34 Palestinian civilians by the Israeli military, in conjunction with the assassination of Bahaa Abu al-Atta on Nov. 12.

“We think this is really important to show to Oberlin students … to commemorate and celebrate these lives [of people] who died from imperialism,” said College third-year and SFP Liaison Alex Black Bessen.

Most importantly, SFP and JVP want these talks on campus to turn into actionable change and open dialogue. The groups will be hosting a debrief and workshop around the past week’s events on Saturday at 2 p.m. in Wilder 115.

“It’s good to have a conversation to … make sure people know where we [all] stand in terms of what [speakers are] saying,” said College first-year and SFP member Audrey Tannous-Taylor. “It can be powerful to take some of the energy that comes out of these talks, that the speakers inspire in people, and find a way to more tangibly put it towards something.”