Art History Students Curate Exhibition About Abolitionism

Featuring pieces from Oberlin’s Special Collections and Anti-slavery Collection, “Subjects of Freedom” is a critical examination of the Oberlin’s historical narrative concerning slavery and abolition.

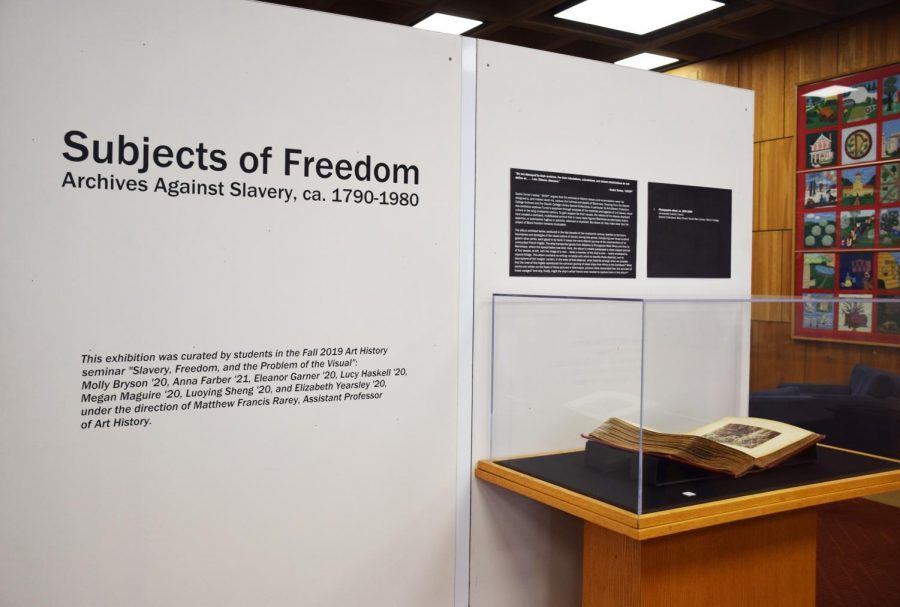

“Subjects of Freedom” seeks to challenge Oberlin’s popular abolitionist narrative as the newest student exhibition at the Mary Church Terrell Main Library that opened Monday. It was curated by students in the seminar “Slavery and the Problem of the Visual,” pioneered by Assistant Professor of Art History Matthew Rarey, and acts as a companion show to “Afterlives of the Black Atlantic,” which opened at the Allen Memorial Art Museum in September.

Institutionalized slavery in what would become the United States began on Aug. 20, 1619, when enslavedAfricans were brought to Point Comfort, Virginia Colony on the English warship White Lion. Rarey, along with the Ellen Johnson ’33 Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Andrea Gyorody, commemorated the 400th anniversary of this event by curating “Afterlives,” an exhibition that featured multimedia pieces about slavery from the United States, Europe, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa (“Slavery’s Modern-day Impact Felt in ‘Afterlives of the Black Atlantic,’” The Oberlin Review, Sept. 6, 2019).

Rarey and Gyorody also sought to create a secondary exhibition of special collections from Oberlin. Through “Subjects of Freedom,” Rarey’s students have the agency to present a show about the contested histories of slavery abolitionism and anti-racism. These conversations are ongoing outside the classroom: Elusive Utopia: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Oberlin, Ohio by Emeriti Professors of History Gary Kornblith and Carol Lasser, published in 2018, engages in these same issues.

Through a series of assigned essays in the first half of the semester, Rarey wanted his students to tackle the problem of slavery as a historical trauma across several continents. The “problem of the visual” in the seminar’s title, therefore, is how to visually represent that history in a way that does justice to it — a problem to which the exhibition seeks to propose a solution.

“As we were looking at the visual culture around abolitionism in the 19th century, especially in the United States … a common move that was made was to depict Black bodies in trauma in order to underscore the horrors of slavery,” Rarey explained. “And of course, the very problematic move there is [that] we should only push against this system when we can come to know or personally empathize with that trauma.”

Because “Subjects of Freedom” is a historical exhibition featuring visual mediums, both the student curators and viewers must acknowledge the underlying racism even in abolitionism efforts. The exhibition seeks to not only inform viewers about why abolitionist history was problematic, but also identify that rhetoric within unexpected artifacts.

For example, the 1808 fold-out map from History of the Abolition of the Slave Trade by Thomas Clarkson appears to simply be a river map, but in mapping a genealogy of abolition that excludes any Black names, Clarkson strips Black abolitionists of their agency and outlines an inaccurate history of abolitionism.

For Rarey’s students, the curating process involved placing their objects in the classroom space and walking around, trying to find connections and generate dialogue.

“In this class, because you are curating the show… you are more involved in this process… your discussion is part of the outcome you will reach,” said College fourth-year Luoying Sheng said. “I’m more willing to speak out in this [class] because I feel like I’m really contributing to this project and [making] it happen with other people.”

Most notably, Sheng has cited Rarey’s classes as a place where she can find her voice as a non-white, non-Black, international student in American racial discourses.

“For the 20 years I grew up in China, I never [had these] conversations… because it just [was] not my world, just not related to my life,” Sheng said. “And then when I came here, I found that, every minute, when you watch TV, when you’re talking to people, that this is actually a very big part [of American life]. It’s just very interesting [to] me being non-white, non-Black to [get] into this history and this conversation.”

Similarly, College third-year Anna Farber credited the seminar for forcing her to face difficult questions about slavery and later abolitionist initiatives in the 19th century.

“I loved the idea of being able to use academic frameworks to show other Oberlin students just how much [archival material] the College has,” Farber wrote in an email to the Review. “There’s also the fact that it is fraught how Oberlin, a predominantly white institution, has so many artifacts of antislavery and how a lot of those objects honor white people and their work rather than Black struggle… Professor Rarey did a great job encouraging us to think critically about our positionality in relation to both the objects and the people whose history is being told and neglected by them.”

“Subjects of Freedom” is only a small sliver of the conversation about abolitionism and slavery. Head of Special Collections and Preservation Ed Vermue gave students suggestions for additional pieces to look at and helped with physical preparation.

“Authenticity and bias in imagery is not necessary as easy and obvious as we like to perhaps think,” Vermue wrote in an email to the Review. “If we apply this lesson to Oberlin’s past, and the self-congratulatory way in which we like to tell the world about that past, it’s possible that stories are much, much more complicated than we know.”

Rather than attempt to resolve the problematic nature of promoting abolitionism through Black trauma, the exhibition is “a manifestation of our continued confusion and complication about the issues that it presents,” according to Rarey.

“I hope that viewers take away how… [abolitionist] visual culture tends to reproduce racial hierarchies and racial inequalities even as it was purportedly anti-slavery in the 19th century,” Rarey added. “I also hope that viewers will take away a sense of feeling empowered to continue to contribute to that narrative around the exhibition and to add to it.”

“Subjects of Freedom” is currently on display on the main floor of Terrell Main Library, and will be until Feb. 29. The exhibition will be permanently viewable on Omeka, a digital platform used to display exhibitions, archives, and scholarly collections. The Omeka exhibition features more detailed descriptions of each piece and their relation to other pieces as well as further insight from the seminar students.