Poetry Event “Afterwords” Reflects on Allen Exhibition

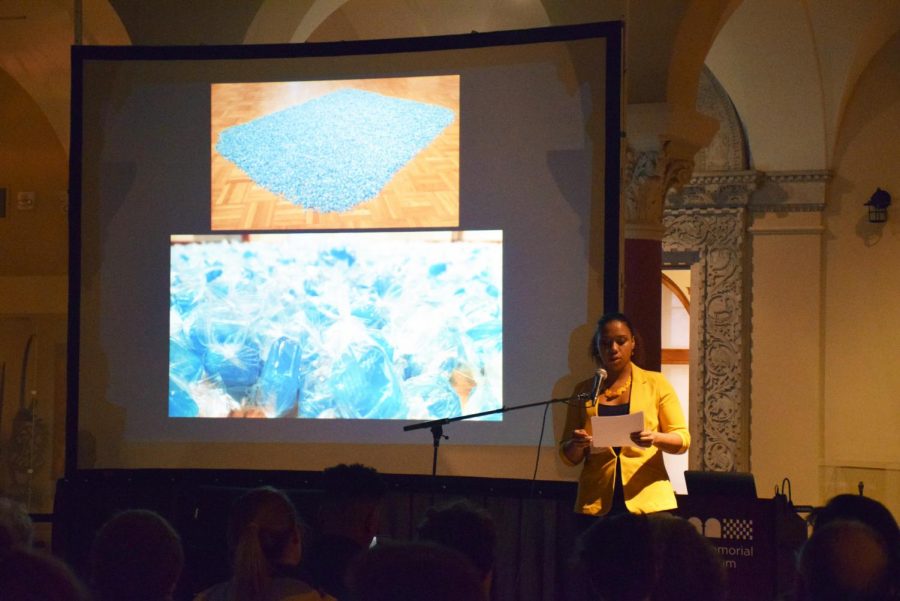

College fourth-year Kaitlyn Rivers reads her poem “Palatable Perception” in front of “Untitled (Revenge)” by Felix Gonzalez-Torres.

Students, faculty, and community members gathered at the Allen Memorial Art Museum for “Afterwords: An Evening of Poetry at the AMAM” this past Tuesday. The event was in tandem with the “Afterlives of the Black Atlantic” exhibition, also at the AMAM. “Afterwords’’ featured spoken word poetry by nine students who not only responded to the exhibition, but added to the art and left the audience with more to reflect upon.

The event was co-organized by members of OSLAM and the Oberlin Creative Writing Department, particularly Visiting Assistant Professor in Creative Writing Lynn Powell and Assistant Professor of Creative Writing Chanda Feldman. “Afterwords” also commemorated Toni Morrison, as it was inspired by The Foreigner’s Home, a documentary directed by Associate Professor of Cinema Studies Rian Brown-Orso and Professor of Cinema Studies and English Geoff Pingree. Through exclusive new footage, The Foreigner’s Home expands upon the 2006 exhibition of the same name at The Louvre in Paris, which Toni Morrison guest-curated. In the exhibition, Morrison featured artists whose work dealt with issues surrounding race, identity, and what it means to be “foreign.”

Andrea Gyorody, who is AMAM’s Ellen Johnson OC ’33 assistant curator of modern and contemporary art, explained that the poetry reading event had been planned alongside the exhibition because “Afterlives of the Black Atlantic” shared similar themes as The Foreigner’s Home.

According to Gyorody, there are many ways in which ‘Afterlives’ and the documentary are connected, such as displacement, time, and travel. For example, artist Kameelah Janan Rasheed’s black banner in the exhibition asks “ARE WE THERE YET?” in white block letters, echoing the questions Toni Morrison poses at the end of the film: How does history progress? Where do we go from here?

As each poet performed, the projector behind them showed the specific piece from the exhibition that inspired their writing. College fourth-year Kaitlyn Rivers and College third-year Sierra Jelks both discussed how the ‘Afterlives’ exhibition resonated with them. Articulating an emotional reaction to the art exhibition proved to be a unique challenge.

Poetry is often more stripped down and sparer than prose, digging at the emotional core of language. Gyorody noted how, compared to the informative and educational nature of art exhibitions, poetry comes from a much more personal vantage point.

“[Assistant Professor of Art History Matthew Rarey] and I both very much wanted the programming around the exhibition to provide opportunities to highlight the voices of scholars of color in particular who have been formative to our own thinking about these issues and the works in the show,” Gyorody said. “And in that same way, we wanted the poetry reading as it is in The Foreigner’s Home, in the scenes that inspired it, to be a space for student poets of color to reflect on the themes of the show. And I think that’s part of why the poems are so emotionally powerful because they represent intensely personal content for the people who have written those works.”

Initially, Rivers was hesitant to perform in “Afterwords” precisely because of its emotional, personal tone. Her poem, “Palatable Perception,” is an indictment against the sugar market, its historical dependence on slave labor, and the present-day ignorance toward that history, particularly by white Americans. It is directly inspired by “Untitled (Revenge)” by Felix Gonzalez-Torres — a pile of blue candy laid on the exhibition floor for visitors to take and eat. Ultimately, Rivers decided that she wanted to share how the exhibit resonates with her.

“I think a lot of times people walk into installations like that — without reading labels, without knowing the backstory — and just kind of pass by it like it’s just a piece of art, when [for] some people like us, it’s so much more than just an art installation. It’s a history, it’s people’s stories, it’s their lives. And it’s the modern issue that we live in right now,” Rivers said.

Inspired by the exhibit, the poets grappled with important, piercing questions.

“I feel like my poem and ‘Afterlives’ and Toni Morrison’s work all deal with the pervasive historical trauma of slavery and the fact that that’s something that unites both the past and present,” Jelks said of her poem “A False Juxtaposition.” “It’s just a thread that continues to have an effect on just the diaspora. … It’s more of an imagined space of, like, how do we imagine trauma, how do we create, how do we visualize it?”

Similarly, College first-year Fafa Nutor wrote about the urgent need to convey, as clearly as possible, how differently Black and white students occupy, learn about, and respond to museum exhibitions like “Afterlives.”

“It has become increasingly apparent to me that non-Black people, especially those who are white, do not understand the gravity and the sacred nature of these [museum] spaces,” Nutor wrote in an email to the Review. “Black history and art and other facets of who we are have been taken from us for centuries. When I and other Black people visit these spaces, we are connecting with entities and energies that we have been divorced from. My visit [to “Afterlives”] was a spiritual experience. [Non-Black students] can simply do their homework and bounce out.”

Jelks and Rivers went on to explain how Toni Morrison was one of the pioneers of Black literature, and how they felt compelled to continue her legacy by contributing to “Afterwords” as poets of color.

“We’re writing as Black women about these subjects, and all of our poems are vastly different,” Jelks said. “We have vastly different backgrounds.”

The diverse content within the selection of poems at this event alludes to the vastness of people’s experiences. No one poem can fully encapsulate the entire Black experience, but each poem is a personal and, most importantly, genuine contribution toward it.

“I think it’s important for every student to go see the exhibition if not only to learn about your history, or your historical involvement in it, or how are you involved yourself now,” Rivers said. “Because it does play on historical and contemporary issues, and if you are not working to fix those contemporary issues, what are you really doing?”