“This Ain’t No Video Game, We Want Outta This Circus:” Oberlin Artist Explores Stigma During COVID-19

A new collaborative art project created by Oberlin resident Tekikki Walker, OC ’12, and Calgary-based Simone Saunders was unveiled online on April 29 as part of The Social Distancing Festival. The online festival aims to showcase work by artists whose careers have been impacted by COVID-19 restrictions, like the closure of galleries.

In an effort to foster an artistic community, festival organizer and curator Nick Green paired artists on the “Long Distance Art” portion of the site. Green paired Walker, who creates digital collage and photo sculptures, with Saunders, who primarily works with hand-tufted textiles. The duo created a project responding to how the pandemic has impacted Black Americans.

Walker and Saunders named their series “This Ain’t No Video Game, We Want Outta This Circus.” The project includes four pieces, two from each artist. Together, the pieces form a conversation about navigating a history of enslavement, perpetual discrimination, race-based politics, and heightened racial tensions during COVID-19.

“I’ve been really inspired by a theme that deals with race, culture, and a lot of religious undertones speaking about the experience of Black people in America,” Walker said. “I wanted to explore more of that and see how the pandemic was impacting Black culture. Lo and behold, we found this article by The Washington Post, and a lot of Black men were being harassed or being unjustly profiled in spaces just for wearing protective gear.”

The Washington Post article, (“Two black men say they were kicked out of Walmart for wearing protective masks. Others worry it will happen to them,” April 9, 2020) explained that Black people who cover their faces are sometimes assumed to be criminals or gang members. Kip Diggs, a Nashville resident stated in the article that, as an African-American man, he has to be cognizant of how others perceive his appearance. Diggs explained that he wears masks in the colors, “pink, lime green, Carolina blue” to look less “menacing” and reduce the risk of racial profiling.

Saunders and Walker were struck by Diggs’ description. The pair explored how clothing colors are racialized in their collaborative series, using Diggs’ mask colors as a starting point for their palette. Saunders incorporated the colors in her textile pieces, and Walker contrasted hot pink, grass green, lapis lazuli against each other.

In addition to drawing a color palette from Diggs’ comment in The Washington Post article, the pair was also inspired by the Maya Angelou poem “We Wear the Mask.” The final product is an intimate remote collaboration between the two artists. Saunders explained that the two chatted online to discuss the pieces before showing each other what they created.

“That was a bit of a nerve-wracking [to] share because we were both a little self-conscious learning what the other person had done, so it was a bit of a surprise, but a happy surprise, and it was a really exciting process,” Saunders said.

In her textile pieces, Saunders depicts two portraits of Black figures, one covering their face with their hands and the other wearing a face mask. The words “Black Lives Matter” are woven into the backgrounds of both pieces.

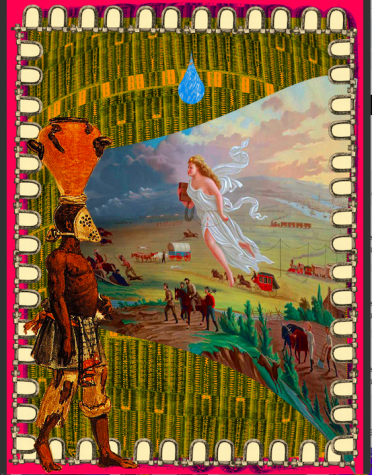

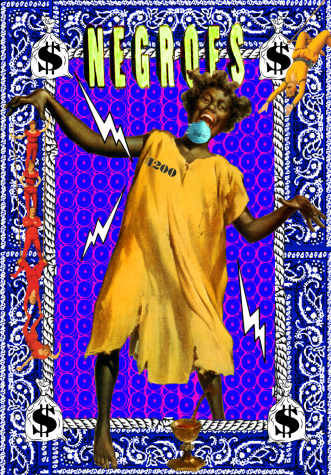

Walker’s collages feature cultural icons like Topsy from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In Walker’s piece “For the Eye What Does for the Ear: Topsy Turvy and the Black Lamb,” Topsy wears a protective mask, stepping out of a frame of a paisley bandana, while white circus men swing toward her head and hang from her hand. In Walker’s other piece, “The campaign of trousseau: a conduit, a gag, a faux pas, and a war,” she centers John Gast’s depiction of Manifest Destiny, surrounding the infamous painting with slave ship diagrams that have been layered and warped. The piece also features a Black man from a Jean Baptiste Debret painting, who wears an iron bit.

“I was really focusing on the history of slaves or enslaved individuals having to wear the iron bit, basically controlling their mouth movements, or being used as a torture device by their masters,” Walker said about the piece. “That’s what I felt like tying old history into something that’s more current with the facial masks — the Black men being harassed and being profiled, and being silenced, just for existing.”

Walker’s ability to tie the past to the present is what attracted Green to her work when she first submitted to The Social Distancing Festival.

“I am obsessed with her work. I think it’s so deep and evocative, I think that it challenges you in a really surprising way,” Green said.

Walker and Saunders are one of three remote collaborations featured in The Social Distancing Festival. Green hopes that the festival can continue as long as artists need support.

“I don’t even know the next time I’m going to be able to cut my hair, so I really don’t know what the future holds for this site,” Green said. “What I do know is that artists are going to continue to need something that provides them with the motivation and inspiration to stay creative, and a connection to the artistic community.”

Walker mentioned it was incredible to contribute, thanking Green and Saunders, and attributing some of her success to her experience at Oberlin.

“Oberlin is one of my homes,” she said. “I wouldn’t be where I am if I did not have the opportunity to attend.”

To view Walker and Saunders’ series “This Ain’t No Video Game, We Wanna Get Outta Here,” visit www.socialdistancingfestival.com/longdistanceart/calgary-and-cleveland.