Thank You, Dr. Tommie Smith

Angelo Cozzi, courtesy of Wikipedia

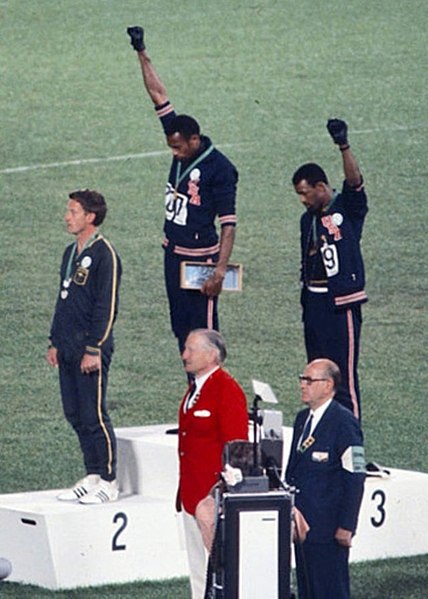

Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising a black-gloved fist at the 1968 Summer Olympics.

The Oberlin College Athletic Department, the Heisman Club, and the Presidential Initiative on Racial Equity and Diversity hosted “The Fist is Still Raised: A Conversation with Dr. Tommie Smith.” Tommie Smith, gold medalist in the 200 meter dash at the 1968 Olympics, is famous for the human rights demonstration that he and his teammate, John Carlos, performed on the ’68 Olympic Podium. They each held up a gloved fist in a silent protest of ongoing civil rights injustices. After the ’68 Olympics, Tommie served stints as Oberlin College’s athletic director, a track and field coach, a football coach, and a men’s basketball coach. The talk was facilitated by George Smith, OC ’87 and Heisman Club member. The two discussed the ’68 Olympic demonstration, COVID-19, activism, and Oberlin culture, among many other topics.

At The ’68 Olympics

Tommie made it very clear that, despite the rumors in ’68 that he and other athletes were considering boycotting the Olympics, he and many of his peers felt that they needed to use their platform to promote change.

“I had to do it,” Tommie said. “It went beyond me then. It had become a situation where the cause was greater than the sacrifice. I had no way out. I didn’t need a way out.”

When asked about the iconic black gloves that he and teammate John Carlos wore, Tommie explained that they had multiple purposes.

“We wanted to point directly to the needs,” he said. “The power, the suffering, the prayer, our belief that we were very socially minded in a way that a lot of people didn’t see Tommie Smith — only a runner, only a student that hadn’t graduated from [college]. … I am a part of a system that needs help. That needs an injection of love against hate.”

The reaction to their demonstration was very mixed. While some applauded their bravery, many more viewed them as ungrateful. On the podium, they were booed. Still, Tommie wasn’t fazed by the response — he expected it.

“Even before the Olympic games, we were taunted [and] we were threatened,” he said. “We were hated before we went to Mexico City.”

Their raised fists are one of the most iconic and widely recognized images in Olympic history — but it was not the last time that they would advocate for social change. Tommie’s future would include working at Oberlin.

At Oberlin

Like many, Tommie was attracted to Oberlin for its progressive reputation.

“Oberlin was the perfect place — and I have heard it still is — to mend wounds which really separate people,” Tommie said. “Church from state, community from the College, and other things that any community needs to be viable moving forward democratically.”

Despite his strong ideals and impressive background, he was fired after six years at the College. Even though his tenure didn’t end the way he would have liked, Tommie is still proud of the work he did.

“At Oberlin I had a chance to move someplace where I could work, I could think, and I could be viable in a system that was already planted and needed work,” he said. “That’s what I was most proud of — a system that needed work and people that depended on what I did.”

His time at Oberlin has helped shape and mold his life since leaving the College.

“[My Oberlin experience] is still with me because I am doing the things now that I wanted to do there,” he said. “I didn’t stop doing what I wanted to do. I had to hunt and find out another way of doing the same thing.”

At Our Current Juncture

Many were curious coming into the conversation about how Tommie viewed the latest wave of protests, boycotts, and demonstrations in athletics, including the actions of former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick. Tommie saw many similarities, but not much change.

“It’s 52 years later,” he said. “That’s basically it.”

While the fight may seem very familiar, Tommie was quick to praise modern athletes for the steps they’ve been taking to advance the conversation.

“Athletes are beginning to use their brains, not just their brawns, to open up doors to where they can speak, especially the younger generation,” he said. “Don’t just sit there and take a beating or mental beating: Speak what’s on your mind and challenge the system to help reawaken those who are sleeping.”

Beyond athletes and their activism, The Black Lives Matter movement has been a defining part of the current discussion surrounding human rights.

“Moving forward, the Black Lives Matter organizational platform is very vital,” he said. “Racism is systemic, and it needs to be addressed, and it is being addressed. It’s not going to be cured overnight, and that’s why the Black Lives Matter movement is so important: … There are so many people involved, and it touches a lot of bases which have not been touched before.”

At The End Of The Day

Maybe more so than anything he said, I will never forget how Tommie carried himself in this conversation. Even though it was on Zoom, and I knew he couldn’t see or hear me, I was nervous leading up to the talk. I was quickly put at ease when, in his first sentence, Tommie joked with George about their shared last name. The conversation was littered with quips and funny remarks from Tommie.

Moments later, George’s connection dropped, and Tommie was left alone on the webinar call. Instead of faltering, he continued on, describing how he has been able to manage stress and health during the pandemic before transitioning into the topic of racism, comparing the threat it poses to the danger of COVID-19.

Throughout the conversation, Tommie was very clear that he did not accomplish anything on his own. He made a point to highlight the work of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, as well as his teammates, like John Carlos — and even his opponents, like Australian competitor Peter Norman.

Although it was never directly addressed, the theme of youth pervaded this conversation. Tommie consistently stressed how young he and his teammates were heading into the ’68 Olympics and how this impacted them, both during and after.

“We were young folks,” he said. “We weren’t Tommie Smith now, John Carlos now, Ralph Boston Now, or Mel Pinder now. We were young people that were trying to defend our necessity to love, get along, and the ability to be secure in our social path of unity.”

At the end of the day, I think the most important thing I took away from “The Fist is Still Raised: A Conversation with Dr. Tommie Smith” was the fact that Tommie felt like he could’ve been my grandfather, or my own father in a decade, or myself in a few decades. This is not to diminish anything that Tommie has, or will, accomplish. It just highlights the fact that he was, and is, just a person. But he managed to do something that changed the world, and led to conversations across the planet. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, civil unrest, and a divisive election, the knowledge that anyone can spark true change was immensely comforting to me.

Thank you, Dr. Tommie Smith.

I want to stress that this is one individual’s understanding and perception of the event. For more information about Tommie’s thoughts on modern activism in athletics, Peter Norman, or his time at Oberlin College, watch “The Fist is Still Raised: A Conversation with Dr. Tommie Smith,” on the Oberlin College Athletics Youtube Channel here.