Edmonia Lewis’ Story Part of a Continuing Culture of Violence Against Black Women

19th century sculptor Edmonia Lewis is best known for her representation of Afro-Indigenous subjects.

Editor’s note: This article contains mentions of assault and racism.

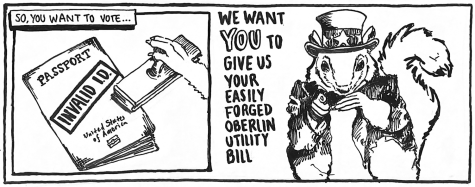

In a Black History Month post on Instagram last week, College third-year Nasirah Fair highlighted the story of the 19th century sculptor Edmonia Lewis, who is best known for her representation of Afro-Indigenous subjects. During her brief time as a student at Oberlin, Lewis was repeatedly harassed and then banned from registering for her last term at school.

Fair says that she chose to draw attention to Lewis’ story not only because it is rarely discussed by the College, but also because it speaks to a continuing culture of violence and disrespect toward Black women on campus that has affected Fair personally.

“I think that when it comes to Edmonia Lewis, her life story mirrors that of so many other Black women, specifically at predominately white institutions [that] abuse them and in the same breath, use their accomplishments for clout,” Fair wrote in an email to the Review. “Black women continue to be disrespected on Oberlin’s campus, [and] this is shown in the way that [there] are only a select few number of Black women professors who have received tenure.”

According to Alexandra Letvin, assistant curator of European and American Art at the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Lewis started at Oberlin in 1859 in the Young Ladies’ Preparatory Department before joining the Young Ladies’ Course from 1860–1863. In 1862, two white female classmates accused Lewis of poisoning their drinks, after which a white mob violently assaulted her. John Mercer Langston, abolitionist and Oberlin graduate, represented Lewis and won her case.

The following year, Lewis was accused of stealing art supplies. Although she was again acquitted, she was barred from registering for her last term. She left Oberlin in 1864 and moved to Boston, where she began her career as an artist, selling portrait medallions of famous abolitionists.

“It’s clear Edmonia Lewis was mistreated at Oberlin — both by individuals and by the institution — but it’s difficult to speak about her experience on a more personal level because, as far as I know, we don’t have any surviving letters or other documents to give us insight in her own words about her time here,” Letvin wrote in an email to the Review. “Today, I think it’s important to balance a pride in Oberlin’s progressive history with a recognition of the stark disconnect that can exist between progressive ideals and the realities of an individual like Edmonia Lewis’ lived experience here.”

To Fair, part of acknowledging this disconnect is honoring Lewis’ legacy in a meaningful way. In her post, Fair pointed out that the Edmonia Lewis Center for Women and Transgender People closed in May 2018, which she wrote demostrates a deprioritization of both Lewis’ memory and support for current Black students, particularly Black women.

“There does need to be some kind of accountability from the college and that could be in the form of creating intentionally, monetarily funded, safe spaces for Black people of marginalized genders on this campus — specifically Black women,” Fair wrote in her email to the Review.

Fair believes that there are many ways the College could do more to honor Lewis’s name and support its current students.

“There aren’t any programs with funds specifically for Black women, although a few of us have been considering restarting Sisters of the Yam, an organization for Black women to come together and support one another,” Fair wrote. “However, so many of us are burned out that it’s been hard to get that off the ground. I think a scholarship could be made in her name, but truly, I don’t have the answers. All that it would take is for someone to put real thought into how to honor her legacy. Up until this point, there’s been no real outrage.”

Currently, the Allen is displaying one of Lewis’ sculptures in its permanent collection. The sculpture depicts James Peck Thomas, who wrote an autobiography about his experience journeying through Europe and the United States in the 19th century as a Black man.

“The AMAM’s sculpture is the only known surviving portrait bust by Lewis of an African American, which makes it particularly important to foreground the identities and stories of both artist and sitter,” Letvin wrote. “Our label does explicitly address the 1862 poisoning accusation and subsequent attack and trial, but it does not mention the second false accusation that prevented her from graduating, which is something we should consider changing.”

While the Allen’s display of Lewis’ work addresses the racism she experienced in her time at Oberlin, Fair says her story isn’t often discussed on campus.

“I am so glad that people are becoming aware of this story,” Fair wrote. “I didn’t realize how many people actually didn’t know — and it clearly goes to show how much work needs to be done here.”