Off the Cuff with Naeem Mohaiemen

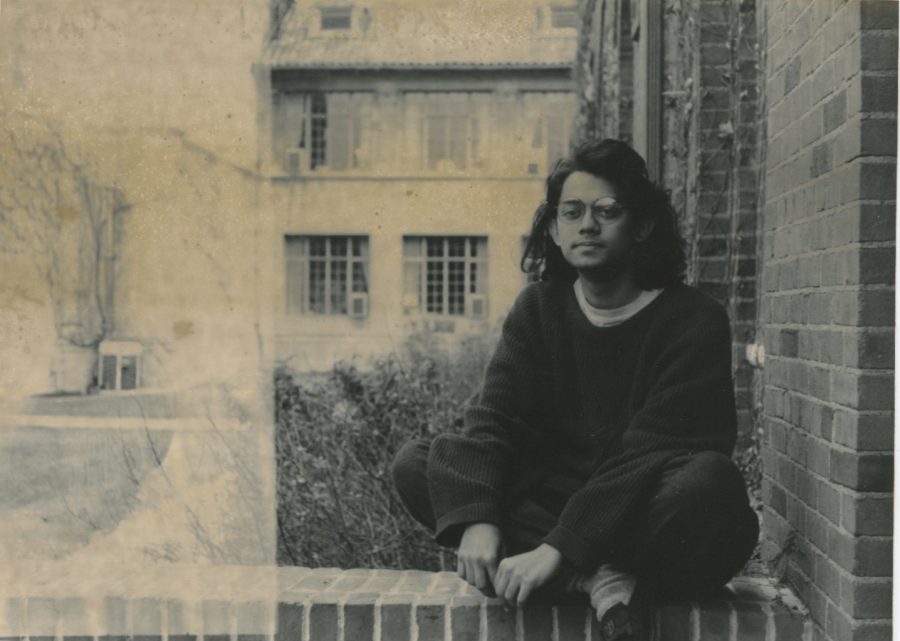

Naeem Mohaiemen, Asia House, Oberlin, 1990.

Naeem Mohaiemen, OC ’93, is a Bangladeshi filmmaker and academic, currently Mellon Teaching Fellow at Columbia University, New York, and Senior Fellow at Lunder Institute of American Art, Maine. He was previously a Guggenheim Fellow (2014), and a finalist for England’s Turner Prize (2018). His first fiction film, Tripoli Cancelled (2017), is on display at the Cleveland Museum of Contemporary Art.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

From your time studying Economics and History at Oberlin, how did you arrive where you are today?

Stephen Sheppard, who was one of my economics professors, enjoyed having me as a student, but also understood that my mind was somewhere else in terms of what I wanted to do. He could see the energy with which I did certain other things on campus. … He asked, “So what are you thinking of doing next?” during fall semester of my graduating year. I gave a very typical reply, “Oh, I don’t know. I was thinking maybe I would do a Ph.D. in development economics.” And he just said, very gently, that students come from South Asia, they do developmental economics, and then they become consultants at places like the World Bank. It’s one of the most expected boxes. That’s all he said, and I just remember thinking that I hadn’t thought it all the way through.

That’s when I decided to apply for the [Thomas J.] Watson Fellowship, which was completely out of left field in terms of what I was thinking of. I applied for a history project, not an economics project. I went back to Bangladesh for a year, which completely changed my path; because I went there, I shot a ton of video on this oral history project, and then I came back to the U.S. to work and I got a job at HBO television— in the hopes that if you’re inside television, you’re much closer to the filmmaking apparatus.

I think this idea that you are not bound to a standard expected path because of what your major is, was really inculcated in me at Oberlin. … Oberlin wasn’t only about preparing you with specific skills that you’re going to use directly. It’s about the approach, for which I think my professors were amazing. They were offbeat themselves. They probably came to Oberlin because this is where they fit.

What inspired you to found the Muslim Students’ Association?

I grew up in a country where we were the majority to an overwhelming 90 percent. Furthermore, the Bengali Muslim community was allied with majoritarian behavior of the state. Growing up, I was highly aware of the fact that the community I belonged to was directly responsible for the deprivation of minority communities inside Bangladesh, primarily the Bengali Hindu community and the indigenous Adivasi community of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. So you’re from a majority community and then you move for college and the lens is reversed overnight. You’re now in a minority position.

I already ate at Kosher Halal Co-op, which was Kosher for Jewish students and Halal for Muslim students, but there were a large number of Muslim students who didn’t eat at any co-op or didn’t have an organization. Oberlin had just hired their first Islam professor, James Morris. Rabbi Shimon Brand was of course very active in the co-op and started talking to me about what the Muslim students needed and I said, “Well, we don’t even have an organization.” And he said, “Why don’t you put in an application to start one?” So that’s how it started with Shimon and James Morris co-sponsoring and then me starting it. It started, and then soon other students took charge, and built it around certain things. Some of it was political, some of it around weekly and annual rituals, some of us were more interested in an active political identity within the American campus. Writer Mariam Mahmud and scholar Tariq al-Jamil were some of the active members.

What, in your experience, have you observed about American attitudes toward Muslim communities in the last three decades?

Tahir Naqvi, an academic based in Texas, helped me to think through all this in a different way. Soon after 9/11 he said that Muslim as an “identity container” in the United States was becoming ethnicized, meaning it was getting attached to an idea of a certain community in which the Middle East dominates and South Asia is second. There’s a very large illusion in the middle of this, which is the fact that the single largest American Muslim community in the United States is the Black Muslim community and they were absented from the post-9/11 discourse around American Muslims. Arab Americans dominated the discussion, even though the majority of Arab Americans are Christian.

The crisis of Islamophobia and the othering of the last 30 years has created a desire for a unified response, which seems to demand a unified identity, which doesn’t allow certain debates to happen within the community. Or the debates are still happening, but they’re invisible to the larger mainstream because of the necessity to provide a unified message in times of crisis.

The other thing that has changed between 1989 and now … there were times certainly in the 1980s and after 9/11 where I and many others felt, “we need to step forward and speak from within this space,” in order to push back, because there are so few people in the public sphere. It does not feel that way at all now. There are people now who have books, and television presences, and public intellectual platforms. The discourse formed by Mahmood Mamdani’s Good Muslim, Bad Muslim, Moustafa Bayoumi’s How Does It Feel to Be a Problem?, or Alia Malek’s A Country Called Amreeka was absent in our first post-college years. So we were also working in a space where there wasn’t enough theorizing around our experience at all.

As class president ’93 and class trustee ’94–96, what are your thoughts on the changes happening at Oberlin now?

From what I have read, and I admit it’s an inadequate and incomplete picture I may have received at a distance, the financial challenges that Oberlin faces are substantial, and do need to be resolved. … It is not an inexpensive school at all. A large portion of the student body was on scholarships when I came in 1989, so there was a very significant class diversity. … It historically was a quirky school whose quirky reputation was national. It also had a reputation for being a refuge for people who could not find homes elsewhere.

My worry is that if you make Oberlin standardized, there’s nothing different about it. And then why would I come to Oberlin, Ohio? When I was at Oberlin … students came because it was a strange, unique place. I think Oberlin’s administration, over time, especially over the last 30 years, has developed a worry that the quirkiness is somehow a turn-off. … I believe that small, quirky, unprofitable things like Experimental College and OSCA are the lifeblood of what makes it different. If you even reduce that by 30 percent, you’re producing a college that would look like every other college on people’s admissions visits. And then they’ll decide to go to the other one or they’ll make the decision based purely on proximity and finances.

What was your experience with activism in Oberlin? What worked for you, and what didn’t?

From the frame of trying to get things done before we graduated within a four-year timeframe, there were many things we didn’t finish, and we had this feeling of graduating and not seeing it through. … For example, a lot of the struggles African American and Asian American students were waging, to change the curriculum and to diversify faculty, were not achieved by the time we graduated. So there was definitely a feeling of unfinished business, even at the graduation ceremony.

As class president and then class trustee, I had to be on deliberative bodies with the administration, which is a very different role from being in a confrontational, activist relationship while a student. … I think it was always a combination of the protests and organizing on-campus that kept the pressure up until results came, but the administration has never wanted to acknowledge that they were giving in to student demands. So I think that the administration would go through a lot of hoops to make it appear that some decision was happening as a result of a very deliberative process, rather than in response to protests. I think it’s unfortunate because if administrations didn’t see student protest as instinctively somehow antithetical to the smooth running of the [College], then there could be much more working together between students and administration.