A Peek Into Professors’ Bookshelves and Home Libraries

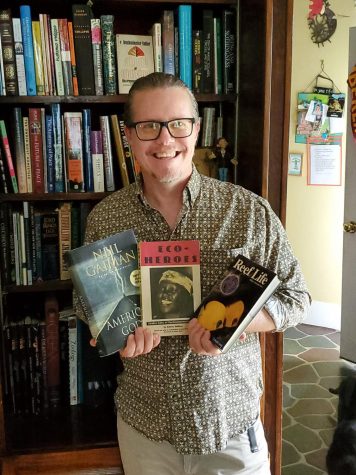

April Mather, visiting professor of Environmental Studies, holds up some of her favorite books.

The first month of the semester sees students reveling in the mild Ohio summer, many curling up with a book in Tappan Square or seeking out a quiet spot in the library. Amidst research, lesson plans, and grading, professors too are finding time to read. Whether devouring some-light hearted fiction, finding hope in the Avatar: The Last Airbender comic set, or reckoning with climate change through the lens of science fiction, Professors’ bookshelves are prime territory for good stories: both within the books they contain and in the memories of how those books got there.

Allegra Hyde, visiting assistant professor of Creative Writing, says that as a writer, you have to be intentional about the curation of your bookshelf, or else things can quickly get crowded.

“I do have some classics in there, like Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, but then I’ve also got weird cutting-edge experimental prose that was kind of handmade and I bought at a literary reading,” she said. “Some of the books are books by friends. Some of them are books that are given to me. Some of them are signed by authors. Some of them I studied when I was a student — but the books that I keep in my home, I try to make sure that they’ve earned their place because otherwise as a writer, books will just overwhelm you.”

Among her bookshelf favorites were Matt Bell’s Appleseed, Jennifer Tseng’s The Passion of Woo & Isolde, and Bryan Washington’s Lot: the Stories.

Hyde didn’t always have such an extensive repertoire of literature at hand. Before she went to grad school, she spent some time figuring things out, and many of the books that helped her along the way were introduced to her by fate rather than selection.

“I was backpacking around New Zealand hippie communes and you know, doing some soul searching,” she said. “And in between communes I stayed at a hostel as I often did. In youth hostels there’s often a rag-tag shelf of books. People leave books, take books, and it kind of is a library that’s ever-changing. And so I would often grab a book from a hostel and trade one that I’d been carrying. And I just happened to grab this book, Charles Baxter’s The Feast of Love. And let it suffice to say it was, it was really good. And again, we could put it on that list of books that blew my mind in some way.”

Sometimes, a really good book can do more than blow your mind: It can blow open a career path.

“I think it was just really being immersed in and stimulated by that book among many other factors that when I got back to back home after six months of backpacking that I applied to graduate school to study fiction,” Hyde said.

But that wasn’t the only way Hyde saw Baxter’s work sticking around.

“Five years later I taught a workshop with Charlie Baxter as a co-instructor there,” Hyde said. “I got to work side by side with this person who had profoundly influenced me.”

Brad Melzer, visiting lecturer in Environmental Studies, spends much of his professional life thinking about the very real consequences of climate change, and finds helpful but disparate predictions in the genres of science fiction and ecological nonfiction.

“Science fiction authors are looking to the future and they’re projecting … historical trends and how those will play out into the future,” he said. “And there’s a lot of brilliant minds. There’s a lot of brilliant authors out there who are projecting interesting ideas and there’s the whole dystopian arm of science fiction. That’s all the bad news scenarios and there are so many of those.”

Ecological nonfiction illuminates brighter futures. One book in particular blew Melzer’s mind, and drove him to focus on ecological design through permaculture: From Eco-Cities to Living Machines: Principles of Ecological Design by Nancy Jack Todd and John Todd.

“When I read that book,” he said, “I truly felt that there was hope for the future of humanity on this planet. We can change our society to work harmoniously with the natural world and survive into the future.”

Melzer noted that hopeful ecological narratives like this one are hard to find, and more important than ever. Among many other inventive ideas in Principles of Ecological Design was that of the “living machine.” John Todd used the living machine to bring back to life a pond in Cape Cod that was so polluted it was considered dead.

“[I had heard] we might never be able to fix washing our bread basket — the topsoil, and it takes tens of thousands of years to produce a single inch of it — down the Mississippi,” he said. “It was this tens of thousands of years scale that I kept hearing. I never heard of a three-year scale to fix our problems.”

Oberlin’s Adam Joseph Lewis Center houses its own model of the Todd’s “living machine” design, and mimics natural wetlands to filter and reuse the building’s wastewater. Inventive ecological ideas like these fascinate Melzer so much that he’s embarking on a project to highlight them.

“I’ve started writing a book about visionary, ecological design that explores kind of blowing the doors open and finding whatever techniques and ideas that we can that will help find solutions,” he said.

April Mather, visiting professor of Environmental Studies, traces her love for reading back to branches of childhood.

“My grandmother knew that reading was important,” she said. “And so she would gift me and my sister every classic book, every quintessential classic novel that one should read to go to college.”

Similarly to Melzer, Mather enjoys a read that cracks open conversations about the future. But she prefers to stay away from the hyper-realistic gloom of dystopia, favoring a read that leaves a better taste in her mouth and a lessened weight in her step.

“I’m not too into dystopian futures,” she said. “You know, if the book gets too dark when I read, especially if it’s fiction, I like to read something that’s going to leave me with some sense of hope, some sense that somehow we’re going to be okay. Something that’s different than turning on the news.”

In moments where the world feels like a dystopian nightmare, Mather finds an escape in another world, this one rendered with vibrancy and optimism and flying lemurs.

“During the pandemic, I ended up becoming acquainted with the Avatar: the Last Airbender graphic novel set,” she said. “I’d never watched the shows or anything before the pandemic, but it was just something that ended up in my home during that time, and I really loved the way it was exploring what is colonialism and what’s the impact of colonialism and how do we envision a future where we acknowledge that colonialism and move forward?”

The Avatar series provided a space and framework to approach big conversations with her children.

“I liked that with my family members who were also reading it, we were able to have these conversations about the implications of colonialism, the implications of prejudice and racism, even though on the surface, these stories were much more light and fluffy.”

No matter what you’re reading, Mather just hopes you’ll crack open a book and get lost in it.

“Summer’s a good time,” Mather said. “I know that term is busy and people have homework, but hopefully, people also have time to go sit in the shade somewhere with a good book.”