Director Ry Russo-Young on Oberlin, Filmmaking, and Nuclear Family

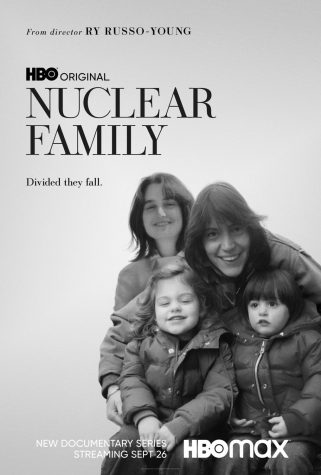

Nuclear Family, produced and directed by Ry Russo-Young, OC ’03, follows her own landmark custody case in the late 1980s. It premiered on HBO Sept. 26.

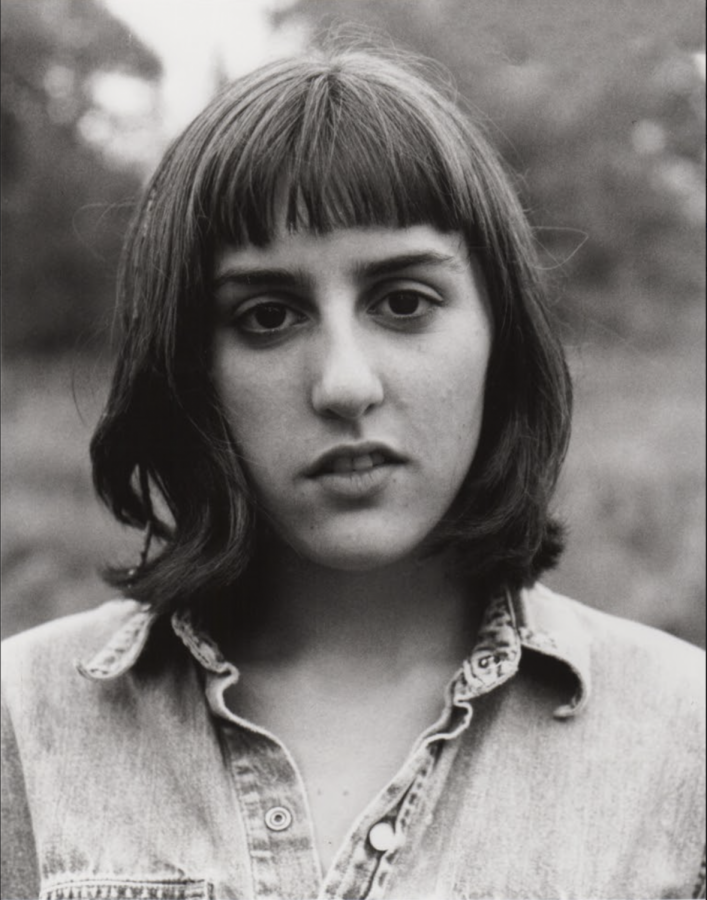

This past September, Director Ry Russo-Young, OC ’03, released her three- part HBO documentary film Nuclear Family which follows her groundbreaking custody case in the late 80s. Born to two lesbian mothers, she and her sister Cade were conceived through two separate sperm donors. The family lived idyllically until Russo-Young’s donor filed for filiation in 1986, a time when the concept of an LGBTQ+ family was nearly unimaginable to the American public. When the court denied her biological father’s bid for paternal rights in a landmark decision, her case was thrust into the public eye, and adolescent Russo-Young was left to grapple with the consequences. A project that began during her time as a student at Oberlin, the documentary offered the now 39-year-old director an opportunity to reckon with her past and the unresolved conflict between her moms’ version of events and her father’s, who died of AIDS in 1998. Prior to Nuclear Family, Russo-Young directed indie films like Orphans as well as larger studio dramas like Before I Fall.

This article has been edited for length and clarity.

Could you walk us through what creating this documentary was like? Did it start with unearthing your family’s tapes and the movie your father made you?

Well, it didn’t start with the tapes. It started with really wanting to process the experience of the lawsuit and to figure out the narrative and own it for myself. That process actually started at Oberlin. I did an independent study my junior year, which was called A Middle Ground. It was a multimedia performance piece. A friend of mine, a composer in the Conservatory, composed the music. It had films in it, but it was a live performance about Little Red Riding Hood. I had my moms dress up in red capes. That was really the first creative attempt to understand the story and to understand who my biological father was to me in my life, to try to figure it all out. At that point, I was making a bunch of experimental films and short films at Oberlin. I don’t know why I did a live performance as opposed to a movie, I just wasn’t there yet. It felt right to do it as a live performance and include all of these films at the kitchen sink. That’s just where I was in my creative development.

Originally, you planned on making the piece a narrative, scripted film; what drew you to the documentary medium?

For many years, I was making narrative films, and I thought, “Well, I want to tell this story. I should tell it as a narrative.” So I tried writing many versions of the script, and it just never felt right. It always felt like I had to simplify the narrative too much — there had to be a good and evil — and I had issues with having a 9-year-old as the lead character. There were just certain limitations with the narrative form. When I won a Creative Capital grant in 2015, I used some of the money to start this project as a hybrid film, which was going to include both the tapes and footage that I had but also actors playing out specific scenes.

Eventually I realized that a documentary would allow me to not know the answers to all the questions. Making the documentary itself would be part of actively answering those questions, and I would do that on camera. I would do it in the making of the film itself. I was looking for a subjective truth because, from the very beginning, I wanted to tell my version of the story. Even now, I have no faith in objectivity. I just don’t really think it’s possible. So from the beginning, I was just trying to find the truth that I was comfortable with, that felt true to me. A huge part of that was hearing the other side of the story, processing it, thinking about it, and allowing myself not to be so dogmatic in believing the version where he’s evil. My moms weren’t perfect, which is the sort of argument or party line I had to follow in order to survive and not be taken away from my family. I don’t blame my moms for that because I don’t think it was their fault. It was the law’s fault that they weren’t recognized as a family. As a person in the middle of my moms and my father over all these years, that realization was part of my coming to peace and finding my own truth in it. And I guess moving back- ward a little bit, too.

A lot of your career has been interested in exploring the adolescent experience, which was clearly a very formative time in your own life. What about teenage life has interested you in the context of your other projects?

Well, I think in terms of mainstream narrative, what’s appealing to me is that there’s so much about identity in adolescent and teen films. That time of your life is when you’re asking yourself these huge, monumental questions: “Who am I? How do I survive in the world? What kind of person am I going to be? How am I going to leave my parents and forge my own way in the world?” Those are big questions that I still find myself asking to this day, and I think those are really valid questions, especially for young women. I want to make movies that dignify the young female experience. I felt like so many of the films made for teenage girls would talk down to them or make their problems seem silly or they’re always about boys. They were always gendered in some way. I just felt like there is a nobility in taking that age seriously, especially for young women.

As you look back on your career, what can you share with current Oberlin students who are aspiring directors and producers?

It’s important to me, as a creative person, to discuss this narrative of instant success, especially now that I’m talking directly to students. We think, “If I’m not instantly successful, I must be a failure,” or that good work comes easily and quickly, just popping out of us. But this project took such a long time — so many forms, so much throwing pizza at the wall and seeing what sticks, trying to do it, and going back and forth on what’s not right. I think it does take a really long time to make good work, both in terms of practicing your craft and just developing the ideas. I’m not saying it always takes 20 years like it did for me, but it’s a lot more work than I thought it would be as a young person. When you start out, you don’t feel like you have a lot of time and you want success immediately. You want to make a living and a name for yourself. There are so many feelings of anxiety wrapped up in that mindset: “Am I making good work? Am I good enough?” I felt all of those things along the way and made a lot of choices because of them. This was an example of a project that was not fast, and that was okay, because it was the best thing for the project.

Can you talk a little bit about what your experience at Oberlin was like?

Oh my god, I have so many memories! I’m still in touch with all my friends from Oberlin, and even with a lot of people who went to Oberlin but I didn’t know during my time there. I’ve gotten jobs through Oberlin; the Oberlin network is really wide and welcoming, even though I didn’t necessarily feel that way while I was there. But those relationships have lasted. I lived in Burton Hall my first year, which wasn’t a super fun experience if I’m going to be honest. Then I was in Keep Cottage for my second year, and that was really fun. I loved it mainly because I lived with all the friends that I’m still friends with — I know their kids and they were all at my wedding. That’s what made it fun — we were all together. I did a few programs abroad during my third year, but then I lived in a huge Victorian house off campus on East College Street. It was a very filthy house. And then my fourth year, I lived right next to Keep Cottage in a little house with two friends. I was a Cinema Studies and Visual Art major, which basically meant I knew I wanted to do film, but Oberlin didn’t have a film production major. I knew I wanted to go into the film industry, but I wasn’t sure if I wanted to do experimental film or art film or narrative film or what, so I just sort of took as much in that arena as possible. I had Professor Rian Brown-Orso, and I remember Professor Geoff Pingree — all those guys are still there right? I had so much fun.