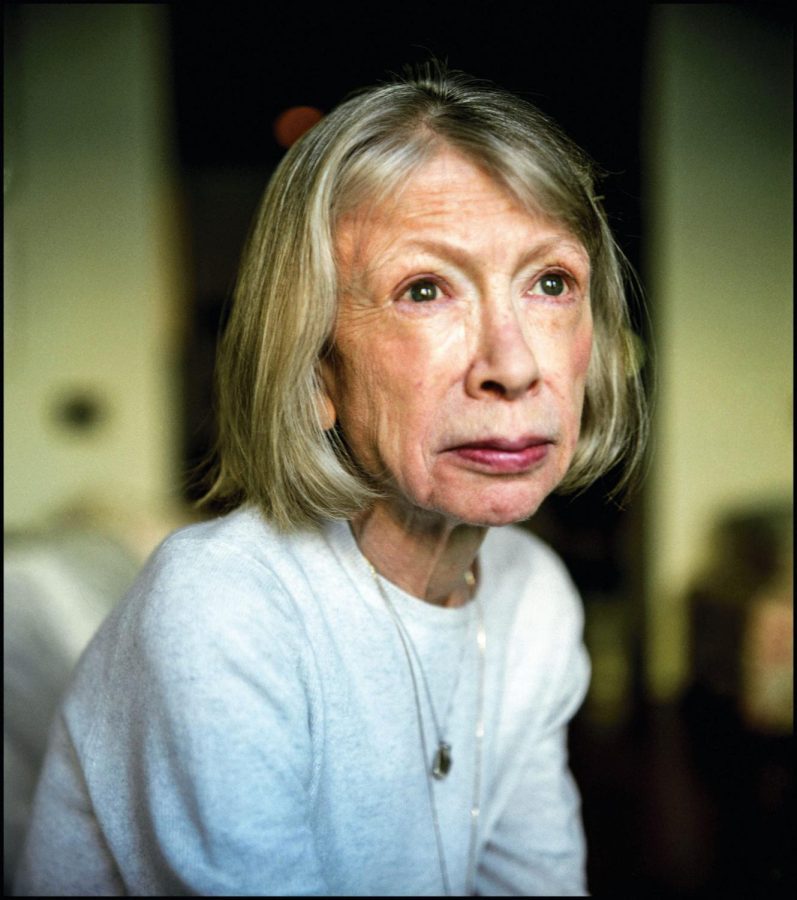

Writer Joan Didion Dies at 87

Joan Didion, famed American author, passed away on Dec. 23.

Joan Didion, whose literary prowess emerged in the 1960s with her essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” died in Manhattan on Dec. 23 from complications of Parkinson’s disease. She was 87. Her most famous works, which include her essay collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem, novels Play It As It Lays and A Book of Common Prayer, and memoir The Year of Magical Thinking, established her as one of the great American writers of the 21st century. Defined by her shrewd, laconic writing style, Didion’s genius lay in her ability to articulate the true and enduring alongside raw, unadorned observation.

The descendant of pioneers who famously began their journey West with the ill-fated Donner Party, Didion was born in 1934 into the Republican traditions of rural Sacramento. While she remained on the West Coast for the majority of her life, always interested in the vestiges of her California childhood, her gaze shifted outward when she went first to the University of California, Berkeley, and then on to New York City, where she was offered a job at Vogue.

Although some of her early work — which The New Yorker’s Hilton Als refers to as the “ones about marriage and motherhood and migraines and life in Malibu” — is certainly the product of a distinctly white-Californian, 20th-century ignorance, Didion’s repertoire comes to question her privilege. Her conservative political imaginings shifted left as she began to see the cracks in her patrician upbringing. She ended her 70-year career most known for her critiques of the Reagan administration, the Bush-Era GOP, and the injustice of the Central Park 5 trial, as well as for her account of her own mental breakdown, rather than her love of Barry Goldwater or John Wayne’s West.

While many remember her for her stunning novels, memoirs, and political journalism, I’m feeling particularly nostalgic for her essay, “Self-respect: Its Source, Its Power,” which first appeared in Vogue in 1961. Written when Didion was in her 20s, it offers an insightful meditation on the underpinnings of true self-respect.

“Once, in a dry season,” Didion writes, “I wrote in large letters across two pages of a notebook that innocence ends when one is stripped of the delusion that one likes oneself.”

In the months before I discovered the essay, I had begun to feel as though I was looking out at the world from someone else’s eyes. That spring, which saw the onset of COVID-19 and long bouts of quarantine, I was lost, disconnected from my internal dialogue, and stuck in a haze of doubt and insecurity. By the time I got around to reading the article toward the end of July, I felt somewhat like a stranger to myself.

Didion coolly refers to this phenomenon as “self-alienation,” a problem of misplaced self-respect, the makings of which, she says, have nothing to do with the approval of others but instead lie “in that devastatingly well-lit back alley where one keeps assignations with oneself.” To have self-respect, “that sense of one’s intrinsic worth[,] … is potentially to have everything: the ability to discriminate, to love and to remain indifferent.” To live without it, she contends, is to live trapped inside a mind perpetually at war with itself — “one eventually discovers the final turn of the screw: one runs away to find oneself, and finds no one at home.”

That summer, Joan Didion taught me that self-respect is about taking responsibility for one’s own life. Having it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re always a good person, kept sheltered in some “unblighted Eden,” but it means you have the courage to accept your missteps and the wherewithal to move past them. “It has nothing to do with the face of things,” she advises, “but concerns instead a separate peace, a private reconciliation.” For someone struggling to connect with themselves, this felt revolutionary.

Throughout her career, Didion wrote of her emotions and opinions with an unfeeling journalistic distance, interrogating her own questions rather than validating her experiences. In Didion’s 1976 essay “Why I Write,” a title taken from George Orwell’s 1946 piece of the same name, she says, “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.”

Didion wrote to sew herself up again; to make sense of her own perspective. She wrote to keep in touch with herself; to dissect her feelings and fears. In her most recent memoir, Blue Nights, she deals with the loss of her daughter — only two years after the loss of her husband — with the same sympathy she dealt with any other subject. Always the reporter, she writes in constant defiance of the easy answer, the immediate virtue. She was interested, as author Zadie Smith argues, in what was just “beneath the seemingly rational or ideological topsoil.”

She begins “Why I Write” with a discussion of the word “I.” The act of writing is “the act of saying I,” she says, “of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind.” There is something unsettling in her authority, something so palpably powerful. In one of the following lines, she refers to herself as a “secret bully,” guiding her readers eagerly and firmly through their own subconscious thoughts.

She understood that her own fear and alienation were symptoms of a changing American identity, a change she deemed worth investigating. She made meaning from despair, grief, and chaos, communicating the essential through the meaningless.

Didion countered my objections in every sentence and convinced me of truths I’d yet to acknowledge, let alone accept. Her words will stay with me always.