Athletes Learning to Balance Body Image and Sport

What does it mean to be beautiful? When do I feel the most beautiful? Am I beautiful?

These are questions that many people who are socialized as women ask themselves — questions that I have asked myself while looking in the mirror fresh out of practice. Covered in sweat and turf, I feel most beautiful when I am athletic.

However, athletic spaces do not always elicit such self-confidence. According to ESPNW, “68 percent of female athletes said they felt pressured to be pretty,” and “30 percent responded with a fear of being ‘too muscular.’”

Abbie Patchen, College second-year on both the field hockey and lacrosse team, believes that societal norms and beauty standards present a unique struggle for female athletes, who must deal with these expectations alongside the pressure to be strong for their sport.

“A lot of this pressure comes from outside of the sports world,” she wrote in an email to the Review. “Regardless of involvement in athletics, females are inundated with ideas about what their bodies should look like. I think a lot of female athletes want to find a balance between being athletic and graceful. I have definitely experienced this. I have played sports my entire life and always have had an athletic build, which at many times in my life I have resented. Different things are expected of the female body in different spaces, so it can be hard to go from wanting to feel strong in one area and then expected to be dainty and pretty in another.”

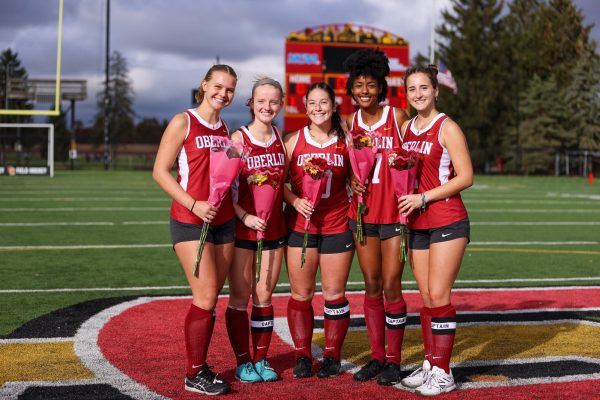

College third-year on the field hockey team, Jackie Oh, believes that female athletes are pressured to fit a Eurocentric standard of beauty, even at Oberlin.

“We see elite athletes on television, magazines, and social media competing with amazing physiques and somehow having picture-perfect action shots,” Oh wrote in an email to the Review. “Unfortunately, I feel like a lot of the appeal for women’s athletics comes from our appearance and if we fit the United States’s standard of beauty. It’s difficult to garner support from fans if we don’t look a certain way or perform with a ‘pretty face.’ I even remember at Oberlin, seeing a sliding scale of women’s prettiest athletics teams on campus.”

Oh added that it wasn’t until the pandemic that she began lifting regularly; she had previously avoided it because of societal pressure to not be “too muscular.” She found that lifting not only made her physically better at her sport, but also had a positive impact on her mental health.

“One of the most common reasons women don’t lift is because they believe that it will make them look bulky or ‘bigger,’” Oh wrote. “I recall thinking this throughout all of high school and the beginning of my career at Oberlin. Whenever I did a workout on my own, it would always be cardio because I also thought that cardio was the only form of working out that was appropriate for my sport. However, during the pandemic, I realized that lifting was extremely beneficial for me, physically and mentally.”

College second-year on the field hockey and lacrosse teams, Sara Fields, believes that athletic standards are heavily influenced by societal pressures surrounding body image. Fields, an outspoken advocate for eating disorder awareness, has personal experience with body image issues as a female athlete.

“As someone who has dealt with issues around eating and body dysmorphia personally, this issue is very relevant to the way I see athletic standards in the context of relative body image,” she wrote in an email to the Review. “When you join a team or sport, females especially must struggle with the idea that they should be small, slender, look put together and graceful. These expectations are highly improbable in the standards among sports with performance and being able to do well. It is incredibly difficult being a female athlete and feeling like I need to look a certain way and portray myself as beautiful during an athletic performance, [especially] when standards are not the same for those who identify as other genders.”

For Patchen, athletic spaces are complex, encouraging body-inclusivity at some times while promoting unhealthy standards at others.

“I think athletics can be body-inclusive because if you are able to perform, then it doesn’t matter what you look like,” she wrote in an email to the Review. “There are also so many sports to try that provide opportunities for people with all different kinds of bodies. However, athletics can promote behaviors that skew towards having a smaller body.”

With many athletes starting their sporting careers at a young age, they are especially vulnerable to harmful rhetoric surrounding body image. Oh has been playing field hockey for nine years and remembers her coaches giving her critiques on her body and the impact that those comments had on her mental health.

“Athletics definitely impacts body image,” she wrote. “Growing up, I’ve had coaches from multiple sports tell me that I need to have a specific physique to do well or to play certain positions. When you factor in going through puberty, seeing rapid changes in your body, and comparing yourself to your peers and teammates, it can be really debilitating to your mental health. I had a bigger build growing up, and I remember feeling really lonely and using athletics as my form of weight loss or changing my body.”

While body image in the athletic community is still an issue, teams at Oberlin are making strides to create an environment that is inclusive and supportive of all body types.

“I think that the field hockey team makes a point to make sure that all of our players love their teammates but also themselves,” Oh wrote. “We make it a point to make sure that we are all comfortable in conversations. I think a major contributor to our team dynamic is making sure that we are all fueling our bodies and being aware that we are constantly losing so many calories, starting with our classes in the morning and afternoons and ending with lifts, practices, and games. We emphasize nurturing our bodies and encourage team lunches and dinners, and meeting with the team nutritionist one on one if needed.”

For all three student-athletes, despite the challenges of body image in sports, being an athlete makes them feel beautiful.

“I feel the most beautiful when I am able to recognize the power that athletics has given my body,” Patchen wrote. “I love knowing that I am capable of much more than what I think my limits are, and that has helped me in so much more than sports.”

Fields explained that being on the field with the support of her teammates and partaking in sports that she loves also makes her feel beautiful as an athlete.

“I feel the most beautiful when I am doing well at something I love,” she wrote. “When I can succeed in my goals and receive support from teammates, I find a lot of love for myself. I can feel that I am doing well and that others can see the work I have put in. My image becomes something on the back burner that I tend to forget about and realize that is not what defines me as a player.”

Oh reflected on how her involvement in other activities besides sports made her a better and more fulfilled athlete.

“Hone in on your sport when the time comes, but immerse yourself with other hobbies and activities that make you happy,” she wrote. “For me, focusing too much on athletics constantly stuck me in a negative mindset; I was constantly thinking about how I can run faster, have better stick skills, and how to compete better. As soon as I started to involve myself in other activities that gave me a different sense of happiness like reading, journaling, going for walks, and lifting, it allowed me to have a different perspective on practices and games.”

Fields cited a piece of wisdom that she was given when she was younger.

“The biggest piece of advice that I would give and that was given to me is that your body does so much for you and is constantly working to support you in everything you do,” she wrote. “Even while sleeping, your body is working to heal and keep you healthy. I think athletes just need to understand that however you see yourself does not compare to the work your body is constantly doing.”

I am lucky to have a team that celebrates my beauty both on and off the field, and for female and femme student-athletes reading this, even if you don’t always feel it, you are beautiful.