Multi-Media Artist Spotlights

The Review has decided to feature student artists this month in an effort to highlight the immense talent on campus. Below, find three student artists who have been working hard on honing their craft.

College second-year Crapps Goodensmith, better known by his stage name, Flatulence Sentience, is one of Oberlin’s leading noise musicians, performing across house shows on South Professor Street and Elmwood Place. His style blends fart-based avant-garde with other sweet melodic gastric noises. His newest song, “Holeeeehollehole goleleHOLE holehohohohoholllllee ho,” has been transcribed here for readers at home:

BFFTTTT FRRPPPP RP RP RP RPPPPPPPP FPBRFTFTTTT

FFFTPPPHHHHHHHFFFFFFTTTTT

PFFFTTTTT FRRRPPPPP RRP RPPPP PBSTFFFVVTTT

PRFPRFPRFPRFPRFPRFPRFPRFPRFPRFPRFPRFPRFPRF BRAPFT BRAP BRAP BRAP BRAFTTTTT PROABBBATFFFTTT FRTTTT PRRR FRRRRFFRFRF

Don’t you feel something right now? I definitely feel something right now. The sonic soundscape created by “Holeeeehollehole goleleHOLE holehohohohoholllllee ho” is unbelievable. I mean … wow. I have chills.

We caught up with Goodensmith after his performance Saturday at his own house, at which we were the only attendees. While describing his artistic process, he poured red paint all over his body, which he says he does “all the time” and “not just for the interview.”

“Usually, I get in the stu’, and I just lay down some really nice, natural farts of my own first, to add a sort of ambiance to the track,” he said. “Obviously, this takes a lot of prep, so a song takes a long time to make — even just step one, building up 30 farts, is a really arduous process. I’ll then create some nice layered work by adding in whoopie cushion sounds and utilizing brass instruments in unusual ways. When I perform live, I replicate those lush layers of farts by having a full band of guys who sit down, one at a time, in chairs equipped with whoopie cushions. So yeah, that’s what you heard when I played ‘Holeeeehollehole goleleHOLE holehohohohoholllllee ho’ just now.”

Another student artist, College first-year Worms Hooperbag, is certainly one to watch. Although they just arrived on the scene last semester, their latest work “Imagine if You Were a Crab and I Came Across You on the Shore and You Had Flipped Onto Your Back on Your Shell and Your Little Crab Legs Were Kicking Up in the Air and Stuff” totally blew us out of the water here at the Review. The project, which was five years in the making, focused on a series of three poems, all in a traditional “Roses are red, / Violets are blue” format. The poems were printed on copy paper in Mudd Center during the artists’ previous performance-art show, which consisted entirely of the artist using a computer to print things out in Mudd. The pieces were hung on a wall behind the artist, who half-spoke, half-sang the poems aloud in a very bad British accent. The event was three hours long.

Hooperbag, who is also known for being that one person who always asks to sit with you at Stevie even though you barely know them, said of the piece that it encapsulates the entirety of their first-year experience.

“Um, yea basically i just thought it was super swag and lit and like fire emoji yknow,” they wrote in an email to the Review. “like idk it was just like so crazy to be like a frosh and like everyone kind of hates you. And also my mom and I are likeeee fighting a lot lately LOL so yea it’s like kind of about her a little bit ig.”

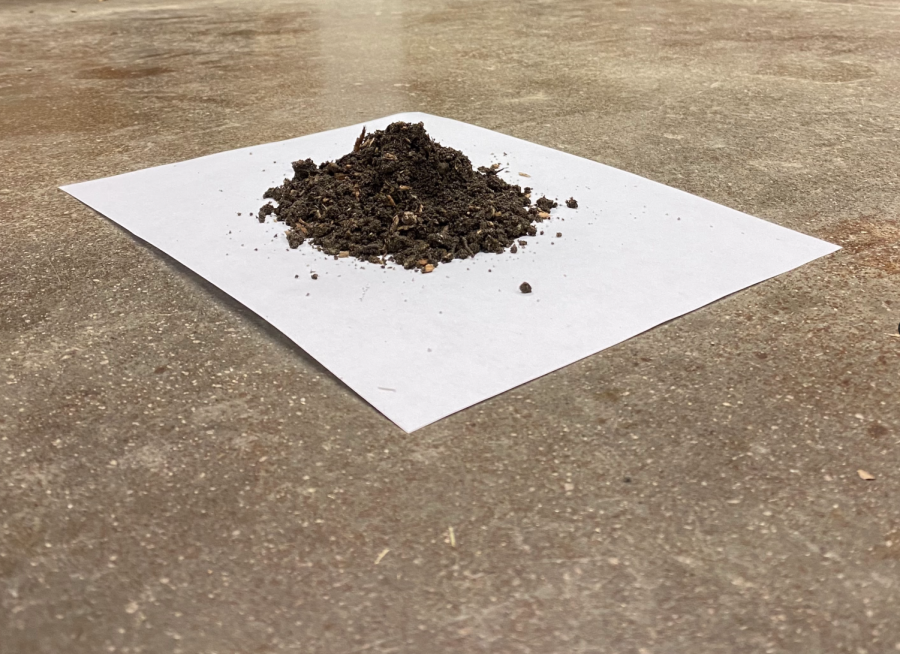

Another piece we’ve been really fascinated by is, in fact, totally anonymous. It appeared in the Allen Memorial Art Museum on Sunday and has yet to be claimed by any artist, though it shows obvious talent and incredible understanding of its medium. The piece itself consists of little more than a small pile of dirt, left on a blank sheet of copy paper, but it shows complete mastery in its use of negative space.

The form lends itself to discussions of border conceptions of identity and finding bliss within the self. The simple mound of dirt on the blank sheet of paper signifies the complex relationship we have with the earth. Steeped in 19th-century hegemonic perceptions of femininity, which cast the female body as an extension of the natural world and as the manifestation of truth, purity and beauty, the work holds a singular, sexualized view of women. Ultimately, the dirt promotes a vision of the earth which is predicated upon its submission to the male gaze. She is “Mother Nature,” of course.

The pile of dirt did not reply to our request for comment.