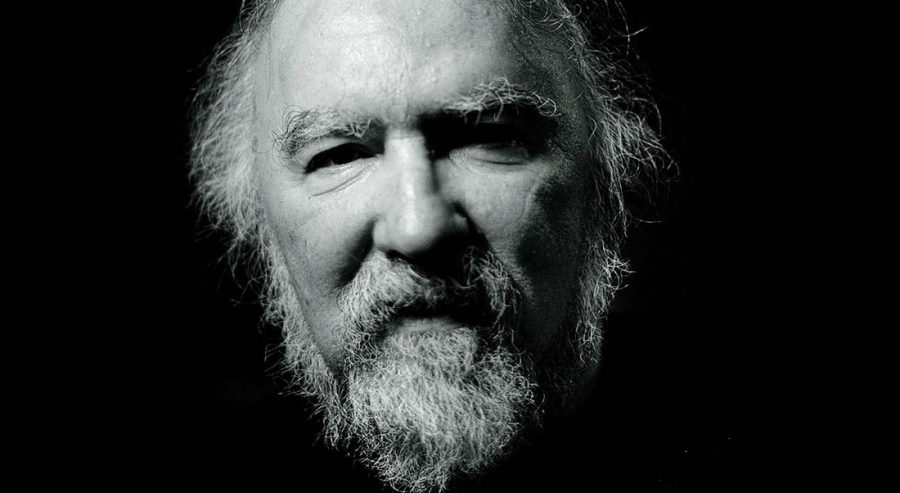

Radu Lupu Leaves Legacy of Mystical Perfectionism

Radu Lupu

Upon hearing of the death of Radu Lupu, the legendary pianist whom I knew better by name than by sound, I decided to discover what made him so powerful. What I found was a player whose demeanor and performance style were an antidote to a music world in which flashiness can often distract from substance.

Through a series of interviews with pianists who had attended his concerts, listening sessions devoted to some of his most acclaimed recordings, and an analysis of concert reviews spanning his decades-long career, a portrait of Lupu began to emerge.

Born in post-war Romania in 1945, Lupu demonstrated his musical genius in early childhood, a talent he would nurture for much of his adolescence through composition and later in the halls of the Moscow Conservatory as a budding virtuoso pianist in the ’60s.

After winning three prestigious international piano competitions in the ’60s, the Van Cliburn in Texas, the George Enescu in Romania, and the Leeds in England, his performance career was effectively launched.

But as he grew, Lupu began to reject the kind of lifestyle and expectations that a concert career would thrust upon him and instead pursued a more private life. In an interview with the Christian Science Monitor in 1970, a young Lupu explained this growing sentiment.

“I used to think what a fascinating life a concert pianist must lead,” Lupu said. “But afterwards I found the ‘glamor’ is not always so glamorous. There are times when I don’t feel in the mood to play, and yet my schedule says I must play. This means I should possess great discipline, but this is a quality I will never, never have. I am a great romantic. I have to feel everything I do; it must be spontaneous.”

As his career progressed, he found a home in the works of later classical and romantic Austro-German composers, whose compositional style was rooted in the idea that music could convey raw emotion without words.

“As he matured, he dropped the virtuoso part of him and became a profoundly spiritual performer,” Takács said. “There’s no flash. It is always pianistically marvelous. He became a champion of the great German literature.”

On the concert stage, Lupu assumed a dignified demeanor. Instead of using a bench, he would sit on an ordinary office chair, allowing him to lean back and exude stoicism.

“He would always use a chair instead of a bench, and that would add to the aura he had on the stage,” Takács said. “He gave the sense that he was above the fray.”

Although relatively few concert recordings of Lupu exist, his rendition of the second movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 clearly reveals that mystical quality Takács identified.

“His eyes are mostly closed when he plays it,” Takács said. “They are also fluttering like he is in some out-of-body experience. It is one of the most beautiful, unaffected, and profoundly expressive performances of that piece.”

Yet, the serene and meditative air Lupu gave off at the keys was not always mirrored in his reactions to his performances. Takács had the chance to converse with him in his native Romanian after a performance, and Lupu revealed a more ruminative and brooding side, dissatisfied with the slightest mistakes he felt he had made.

“He had this really strong perfectionism.” Takács said. “He was pretty much always dissatisfied with his performance, He felt that if he missed notes, that somehow that wasn’t professional. He was very hard on himself, and while he may have had a depressive personality, it contributed to his mysticism as a performer.”

Curious, I wanted to know if I could somehow get closer to experiencing what Takács so eloquently identifies, so I started by listening to Lupu’s recordings of the great Schubert sonatas. I focused in on his B-flat major Sonata, a piece which can be only described as otherworldly, which Schubert wrote as he succumbed to syphilis in his early thirties.

What I immediately noticed about Lupu’s rendition was the airiness he gave the piece; he gave each note space to breathe. The articulation is notoriously difficult to control in this sonata, but Lupu found a way to give each line its own voice, yet always within the vision that Schubert expresses. His art was one of genuine emotion, not gratuitous sentimentality.

It seemed Lupu could slice through the veneer of excess and place the music on a plane purely by itself; there was never a doubt in my mind as to what his intentions were, and I could clearly understand his work not just as music, but as poetry.

This sentiment is echoed by Daniel Schene, professor emeritus of Piano at Webster University, who watched Lupu’s performance of Brahms’ D minor Piano Concerto some years ago. Not lost on Schene was Lupu’s careful calibration of tone color, a feat not easy to achieve in an almost hour-long work that requires enormous stamina, and where simply banging on the piano can be the easy way out.

“His desire was for the artistic truth,” Schene said. “His performance of [it] was very big, and brilliant, but it was all about the meaning. There were countless details that intrigued and thrilled me. Among them was how beautifully he colored his own sound depending on which orchestral instruments he was playing with at any given moment. Such a completeness. Very poetic.”

As I think about Lupu’s death, I wonder what advice he would have given me and other piano students. Perhaps it would be that the music should be paramount to the person. With that in mind, I must now go and practice for a few hours.