Q&A with Courtney-Savali Andrews, Professor of Ethnomusicology

Courtney-Savali Andrews

Courtney-Savali Andrews, OC ’06, is the newly appointed assistant professor of African American and African Diasporic Musics in the Conservatory. This semester, her courses include Introduction to African American Music, an interdisciplinary course that blends music history, ethnomusicology, and Africana Studies. In addition to her degrees from Oberlin in Africana Studies and Piano Performance, Andrews holds a masters degree from Arizona State University in Musical Direction, and a Ph.D. in Ethnomusicology from the University of Wellington. From 2009–2012, she served as a Fulbright Fellow in New Zealand where she researched and taught classes on ethnomusicology. Outside of academia, Andrews has worked with the Seattle Opera as a collaborative pianist, and as a church musician and leader in Auckland, New Zealand.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What was your journey from being a double- degree student at Oberlin to becoming a professor?

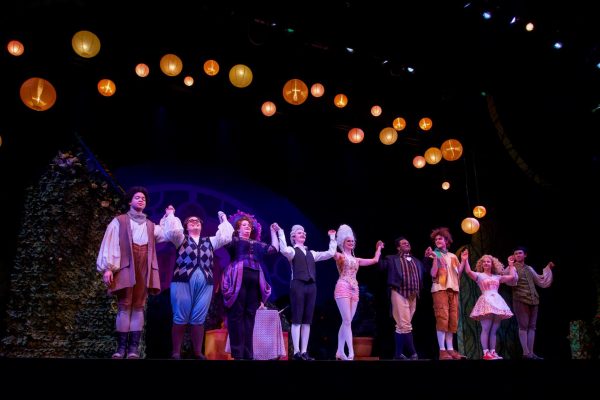

I arrived here at Oberlin as a Classical Piano major, which is an instrument of the European tradition, and an Africana Studies major. Once coming to Oberlin, I learned about Black classical composers and the long legacy that is attached to Oberlin Conservatory, and that started to come through in my playing. My father is African American from Alabama, and my mother is of Samoan heritage from American Samoa. My father is a musician. He’s a jazz Hammond B-3 organist. I grew up in the jazz and blues clubs with him, and my siblings and I are trained conservatory musicians, but we were the only Samoans I was aware of in the U.S. The types of courses that were offered then allowed me to not only express my African-American heritage through my music, but to also start to see connections to my Pacific Islander identity. My professors, especially Professor Caroline Jackson-Smith and Dr. Wendell Logan, were really supportive of me exploring both of my identities in conversation with one another. I was musical director for many of Caroline Jackson-Smith’s theater productions in the Theater department and was also a musical director for five Black churches in Lorain County by the time I graduated from Oberlin.

I come out of the Black Baptist church, and playing gospel and Negro spirituals in those particular contexts is where I would bring what I was learning in Oberlin to the real world. After leaving Oberlin, I went to Arizona State University for my master’s and doctorate and then to New Zealand on a Fulbright to study Samoan opera singers coming out of New Zealand. That Fulbright turned into a Ph.D., and that’s when I realized what I was doing was musicology. It took me six or seven years in my program to even admit that. So for 13 years, I would come from New Zealand to the Samoan Islands through Hawaii, stop in Seattle to visit family, and then back to Oberlin. I’m very connected to the community in the town and the College here, and I think that’s what allowed me to be top of mind when there was a vacancy for someone to come and teach Intro to African American Music.

Do you have a favorite definition of ethnomusicology that you like to use?

Ethnomusicology is the study of cultures in society through the exploration of their musical expression. As musicologists, we go about understanding their social context by using ethnography as our methodology. So that means being among the people and learning from them about their existence and expression. You’re not stuck in the archives. You work on field sites. You have to work out your insider outsider context. You have to learn how to properly engage with people. And it’s culturally specific.

What’s been the biggest lesson you’ve learned from being an ethnomusicologist?

I learn all the time, every day. This work makes you very sensitive to how you engage with people. You are researching facets of their life while also learning how to do what it is that you’re researching. Even when I’m teaching, I’m always trying to figure out what the best approach is going to be to get the best questions out of the students. I have also learned to take into account that I am a Black- and Brown-presenting person that is engaging with other Black and Brown peoples, and there are very specific pivots and protocols that make that relational space mean different things.

Do you have a favorite part about teaching this course or teaching in general?

There is a research project that I’m really excited about that students do in second semester that was inspired by the lockdown. Every student researches a figure, band, or particular subgenre of Black music coming from their exact neighborhood. I did this to illuminate a couple of different things. One is to bring together their experience of having an immediate threat to their life. Two is that all of these different reactions to that process reminded me of the ways that Black peoples have come through the Middle Ages, have come through transatlantic slave trade, and have navigated their lives over generations. The goal is for the students to identify figures that have always had to do that in places that they call home and to identify whether Black and Brown people are still in their neighborhoods. I do that every spring. It’s challenging, but it gets to the heart of the music, the people, and identifying your relationship to it.

How does it feel to be teaching the class that you took as a student, especially one that Dr. Logan taught for so many years?

It’s trippy because I can remember what it was like to sit in class and learn African American history, and American history in general, through this lens of Black music. There was a lot of unlearning that happened there. Now I’m on the other side, looking into the eyes of confusion, pressing up against students’ understanding of history. It’s really rewarding, but it’s also very challenging. I’ve revamped the class to answer issues that we’re constantly facing with the pandemic and George Floyd, and still within the context of Black Lives Matter, so that when students crash into whatever the news cycle is telling us, there’s a way that the course has already addressed that. The music always keeps score as to what is going on between Black people’s overall existence and their context in America.