History of Oppression: Dressing for Rich White Majority

Dressing for success goes beyond colloquialism — it’s a term of deep cultural significance. Watershed moments for students historically underrepresented in academic institutions are underscored by the legacy of knowing that success is how you choose to show up.

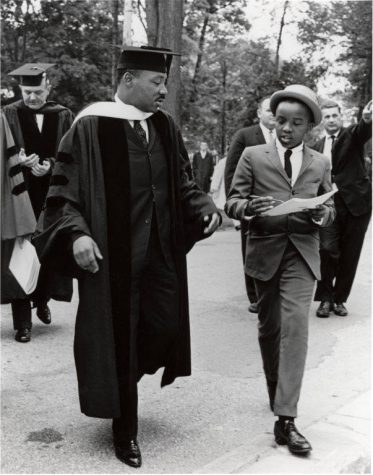

Oberlin’s relationship with Black excellence started in 1835, with Black students being admitted. Scholars and artists were afforded the opportunity to pursue academia at what was then known as the Oberlin Collegiate Institute. Black and Brown folks who were allowed to occupy previously segregated spaces of research and creative discipline were now faced with the question: what does it mean to show up Black when Blackness has been seen as the enemy of excellence?

In Oberlin’s class photo of 1947, student Carl T. Rowan is seated among his fellow classmates.

He is the single Black face in a cohort of white men who represent an expectation of upholding the appropriate aesthetic, which is evident in the sea of blazers and buttons which remove any trace of a cultural presentation that might subvert the visual legacy of white supremacy he’s now been allowed admission into.

Fashion, in this respect, is not purely the choice of repurposing a blazer or wearing a different color of high-top Nike — it’s a means of assimilation into the dominant culture. The barrier to entry for Black and Brown folks has been held upon the ability to uphold a level of visual uniformity within whiteness.

Systematic policies around the appropriateness of ethnic hair and body types associated with women and men of color have been socially normalized within universities and workplace environments, as well as within film and television. The erasure of cultural fashions has led to clothing being used as a tool for blending into oppressive spaces — which means dressing the part.

College fourth-year Saint Franqui spent most of his childhood living with his mom and grandmother in majority-Latino Section 8 housing.

“Growing up, a common phrase was thrown around in my household: ‘Puedes ser pobre, pero no sucio,’ which translates to, ‘You can be poor, but not dirty,’” Franqui said. “Showing up to school in clothing with rips, tears, or holes would signal to people that you were poor, which gave them a reason to treat you badly because of it.”

Oberlin’s relationship with fashion has always been one of obvious importance and timelessness. There is no space at this institution that has not seen the power of clothing used as a form of counterculture and protest. However, this fashion forwardness contrasts the privileges of those afforded the financial flexibility to move in and out of a “poor” aesthetic.

“Since being at Oberlin, I’ve noticed an interesting pattern of students of color being well dressed and put together often,” Franqui said. “In contrast, wealthy and white students rave about their ratty thrift-store finds and go to class in stained, dirty, and tattered clothes.”

The legacy of Black and Brown students at institutions such as Oberlin has been one of proving the value of occupancy. A part of this unspoken exchange has asked for the families of these individuals to teach their children how to dress for the success they’ve been unilaterally denied. This process of looking the part is also paramount in understanding how culture can act as a superseding force in weaponizing presentation for upward mobility.

Oberlin’s institutional history of excellence is a credit to its legacy of Black students, who illustrated the ability to succeed beyond the stereotypes of racialized aesthetics — and look great while doing it.