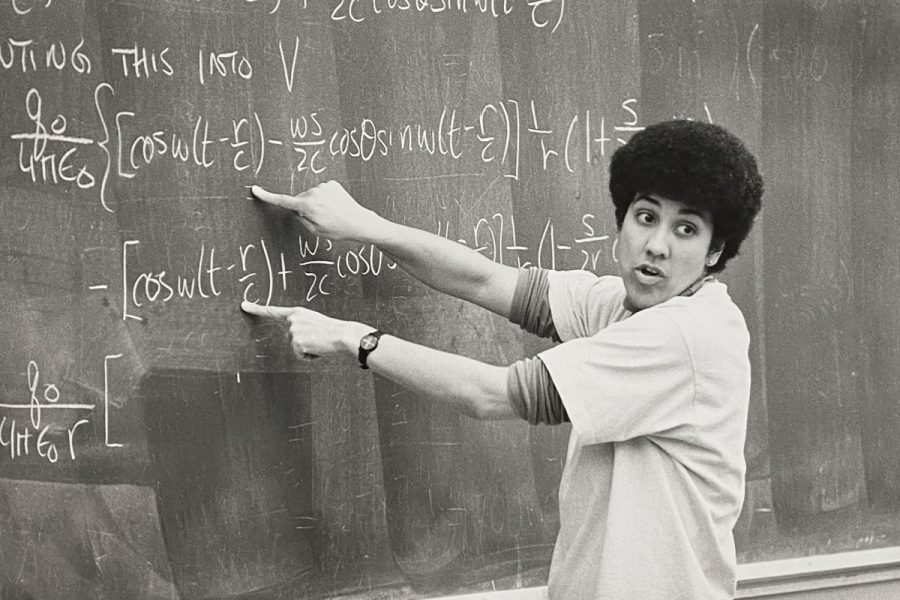

Dr. Mary James, Physics Professor at Reed College

Photo courtesy of Reed College

Dr. Mary James

This Wednesday, the Oberlin Physics and Astronomy department hosted two talks by Dr. Mary James. Dr. James is the distinguished A.A. Knowlton Professor of Physics at Reed College and Co-Chair of The American Institute of Physics’s TEAM-UP task force — a task force aimed at identifying challenges and finding solutions to the systematic underrepresentation of African-American students earning bachelor’s degrees in physics and astronomy. Dr. James’ first talk focused on the ways that physics departments can change their culture and climate to better support African-American students in physics as well as other underrepresented groups. The second talk later that day focused on recontextualizing what access to a college education means, not only in terms of college admissions but also the barriers that stand between underrepresented students and a successful education once on campus.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you tell me a bit about the findings of the The Time is Now: Systemic Changes to Increase African Americans with Bachelor’s Degrees in Physics and Astronomy American Institute of Physics’s TEAM-UP report?

Even among STEM disciplines, physics has a very poor record in supporting underrepresented students in persisting through the major to graduation. In many cases we cannot blame students’ prior preparation or lack of interest in physics for these poor outcomes — the TEAM-UP study controlled for these factors — but rather aspects of the culture of physics are driving them away. One of the things we emphasized in our report was that the student experience is the data. Physicists are really good at collecting and analyzing quantitative data, but they’re not trained in collecting and analyzing qualitative data. So, our social science colleagues on the task force helped us physicists learn how to collect, analyze, and then use our qualitative data.

We collected a lot of qualitative data and found that students needed four things to persist in the discipline. The first is a sense of belonging. This means that they feel that they’re a valued member of the physics community in terms of their relationships to their peers, their relationships to faculty and staff, and to those more advanced in the field. The second is a sense of physics identity, or scientist identity — that they feel they are physicists in the making . The third is that academic courses are taught in an inclusive manner that is appropriate, culturally responsive, and has supplemental support, including culturally responsive advising and mentoring.

The fourth is that they are seen as whole people who are studying physics rather than a brain on a stick. The kinds of things that students said were, “I feel like when I walk into the physics building, I have to hide everything else about myself,” because if they bring any of those other aspects of themselves or their identities into the physics building, they are seen as not serious about physics. It’s important that we as faculty and staff honor students’ commitments, both their commitments to their education and their commitments to family and community.

Those diversity aspects that students feel are less valued and that they have less space for — is this the reason for the specific discrepancy in African-American representation?

Yes, it’s one of the reasons for the significant discrepancy. I’m not saying that these challenges are exclusive to African Americans, but what we found in talking to African-American students were these are the things that they identified as barriers. I think the culture within physics is very hierarchical and individualistic. Many African-American students don’t see themselves in this way, as separate from their families and communities.

I’m a college professor, and when my daughter went to college, I said, “You go to college and you do you. We’ll take care of everything back here.” When I reflected on that later, I was in a sense saying, go be an individual, you have permission to disconnect from the family, from the community back home. But in many African-American households and communities, they’re just not set up that way at all, you don’t have an identity separate from your family and your community. Then you go into a college environment that is telling you “Oh, no, you leave all that behind and you come in here and you do this” — that’s very alienating.

Oberlin is described by students as a very white institution. In your time as Dean for Institutional Diversity at Reed, what changes that benefit students and the institution as a whole have you learned from and would recommend?

One of the things that I try to do is to help faculty become students again. We have to think more broadly about our disciplines: what we teach and why, who the seminal thinkers are in our discipline and why we hold those people up, who is excluded in what we teach and why, and how can we expand our syllabuses and course offerings to think more broadly about the experiences of historically marginalized and underrepresented populations.

That leads, also, into pedagogy. We need to ask ourselves; Who does our existing pedagogy serve well and who does it serve most poorly? We then need to think about the fact that the students who are served well by our existing pedagogy become our best students and are rewarded in all kinds of ways and the students who are served most poorly by our pedagogy are not. How can we make pedagogical practices that serve all students in a way that gives them a sense of belonging, a sense of themselves as emerging scientists, the academic support that they need, and that sees them as a whole person?