FIFA World Cup Builds Community, Connections

Photo courtesy of Juliana Gaspar

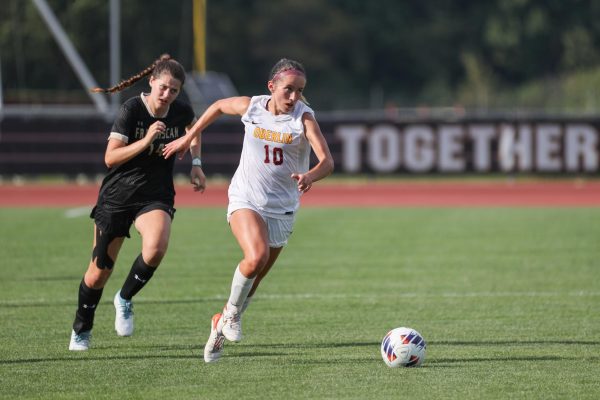

Several students watched the Japan vs. Croatia World Cup game.

The FIFA World Cup soccer tournament kicked off year 22 on Nov. 20 and has brought unlikely connections and community to Oberlin’s campus. Walking through the Science Center in the last few weeks, one might see jerseys plastered on open laptops, hear an isolated cheer echo through the mostly silent atrium, or witness a heated argument about which team should win.

As a Brazilian international student, I didn’t know what to expect watching the World Cup in the U.S., where soccer — or football, as it’s known to most of the world — feels less culturally relevant than in my home country, however true that may be. The familiar feeling of homesickness crept up as my family flooded our group chat with spirited updates about the most recent games. However, I have been pleasantly surprised about the effect of the present World Cup on campus.

College second-year Ava Shigur decided to keep up with the World Cup in one of her classes last week. Not only did she learn more about soccer and how the tournament works, but she also made a new friend in the process.

“I was sitting in one of my classes, and instead of paying attention, I put on the World Cup,” Shigur said. “There was a guy sitting a few chairs next to me also watching. After class, he came up to me and congratulated me on the win since the U.S.A. was playing. He then asked me if I was a soccer fan, which I am not. I’m only watching because my friends are watching and I need to stay in the loop. After a whole conversation about soccer, he introduced himself and now we’re friends.”

It’s not just students who are distracted by the games during class time. Professors can be soccer fans too. College third-year Audrey Weber shared her experience in a class on Monday during the Brazil vs. South Korea game, when her professor was just as eager to stay updated on the score as the students were.

“In my Hispanic Studies class, we finished a couple minutes early after we did some presentations, and in the last five minutes of class, our professor put on the South Korea vs. Brazil game,” Weber said. “There were already a couple people watching the game during class; my professor was even sliding it onto the screen while we were presenting. There was definitely a sense of camaraderie.”

Although some students are willing to give the World Cup their full attention, others have decided to stay focused on their schoolwork. College second-year Eliza Giane won’t miss class for a game, but acknowledges that the World Cup is culturally relevant for her, especially as a Brazilian.

“If I have class or homework, I’m not gonna prioritize watching the game, even if it’s Brazil,” Giane said. “But I won’t tell anyone — I’m gonna hide it with shame if I don’t watch a Brazil game. I’ll lose my Brazilian citizenship if anyone finds out. I don’t care about [soccer] unless it’s the World Cup, because that’s the only time that we [Brazilians] actually have to care. Everyone has to care.”

Giane may not miss class, but that doesn’t mean she isn’t keeping up with the tournament. Unlike American football, soccer doesn’t seem to hold as much importance in American culture as it does in other parts of the world. As Brazilians who are away from home and not surrounded by the familiar yellow and green jerseys during the World Cup season, we crave the feeling of community.

“It’s weird watching the game in the U.S. and everywhere being so quiet,” Giane said. “They don’t freak out for every close hit. It’s not the entire city watching that game like it is back in Brazil. Watching it here with the other Brazilian students makes me feel more at home.”

Watching the games has created connections not just for those who are already established, such as students from the same country, but between more unlikely groups too. College second-year Colvin Iorio co-hosted a watch party for the Brazil vs. Cameroon game at Harvey House, La Casa Hispánica.

“As a soccer player and a soccer fan, I wanted to throw a World Cup watch party,” Iorio said, “At the Spanish house, we watched a Brazil game and there were Brazilians watching it with us, which was exciting. It was a nice atmosphere to watch a game that I had never experienced — anytime the ball got anywhere near either goal, they would start shrieking. It made me feel hyped up too. ”

Going to school in the U.S. for the last four-and-a-half years, I have observed that the cultural impact of the Super Bowl here seems comparable to that of the World Cup in Brazil. However, the difference between the two sporting events has to do with both the nature of the sports themselves and the countries or teams which the players are competing for. The passion behind the World Cup is largely rooted in identity, whereas the Super Bowl’s large viewership may be more rooted in American commercialism. Iorio explained why he, as an American, feels more drawn to the World Cup than the Super Bowl.

“The athletes are competing for their national team rather than for a club or their employer,” Iorio said. “Supporting that feels different than supporting the Super Bowl.”

Whether in sports teams, international student groups, or the general student population, the World Cup has a way of bringing people together to connect, watch, and banter.