Ivy Fu, Multimedia Artist and Graham Grindlay Grant Recipient

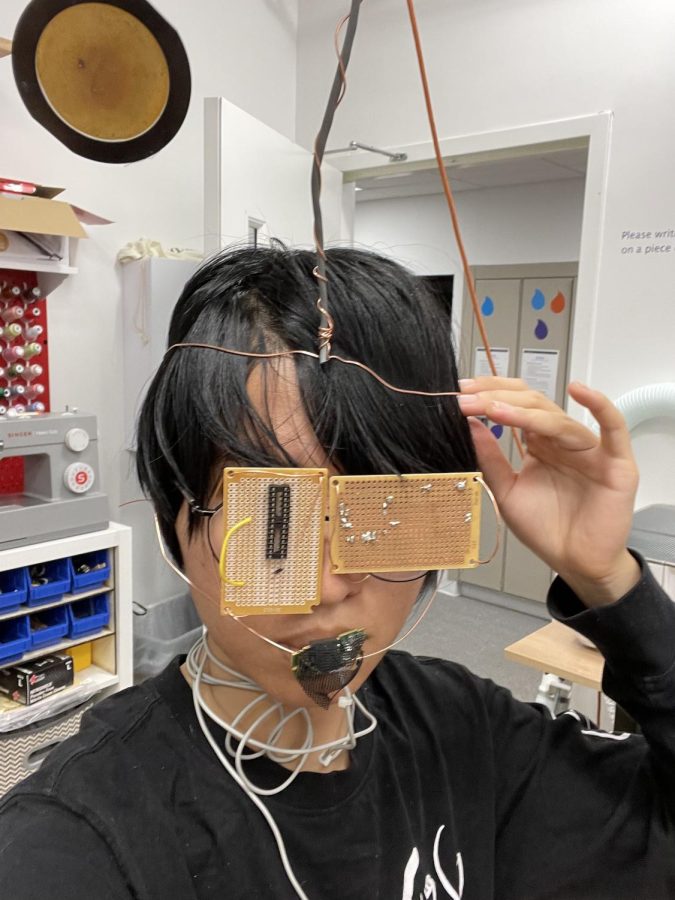

Ivy Fu experiments in the TIMARA makerspace.

Ivy Fu is a fifth-year double-degree student majoring in TIMARA and Art History major. Throughout her years at Oberlin, she has created, conducted, and installed myriad multimedia projects, including Trace, an augmented-reality installation and Junior TIMARA recital that synchronized a scripted story and geolocation-specific augmented reality in a sonic landscape that the Allen Memorial Art Museum’s visitors were able to experience through the iPhone app TraceAllen. Fu was recently awarded the Graham Grindlay grant which will support her visiting and interviewing the immersive multimedia art production company Meow Wolf as research for her augmented reality exhibition The Sentient Bedroom. She will be traveling to Meow Wolf’s site in Las Vegas to develop her work with the company’s team.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How do you synthesize your fields of study through your museum and installation work?

I’m a musician and a multimedia artist and an art researcher, so I try to merge all of those together in research-based performance art pieces, immersive soundscapes, and interactive installations. I made Trace, my junior recital for TIMARA, in the Allen by using location-specific augmented-reality installation that viewers experience by downloading a phone app. You walk into the museum, and there are all of these beacons, which are dual-location data-tracking devices installed right next to the artworks that they are composed for. So when you walk around it and you walk in certain proximity to the artwork, it triggers certain sounds or light multi-composition that has been recomposed and concatenated in real time.

I do a lot of similar work where I try to combine the two sides of my studies. I’ve recently been specifically interested in something that is closer to surveillance and data monitoring because I grew up in China, and recently there have been a lot of situations in China related to COVID and big data tracking and use of monitoring. So, I’m interested in knowing: As normal people in this larger state-governed surveillance, how does an individual maintain agency, and how does the individual know how much is being heard and how much is being used? I think after I went to Darmstadt, a music festival in Germany, and saw Jennifer Walshe and some other scholars present on this project called “Eavesdropping,” a collaboration between the Melbourne Law School and some other artist, I got super interested and just started working. Together with the fact that I was in a TIMARA class at the time about e-textiles, which are textile materials that are also electronic. I realized that technology is definitely a big part in this idea of information agency and in understanding how our reality is reconceptualized by technology. Our reality is reconditioned by the sensory input and output that is so close to our lives.

Your current work seems so couched in this intersection between technology, surveillance superstructures, and individual agency. How did your relationship to your work change after attending the Darmstadt festival?

I migrated into this after I worked on the interactive installation in the Allen — that project was mainly to open the museum space, which usually is a very strict and regulated space. That project was meant to dematerialize the space into something where especially non-traditional museum visitors can feel vulnerable and intimate with the art by directly conversing through sound.

I’ve always been in this intersection of technology and its social implication because of the things I study, but I feel that after viewing the “Eavesdropping” project, I started consciously thinking about how much technology affects our lives and why I’m choosing to foreground technology so much in my art. Before, it was just kind of, “Oh, I’m a major in TIMARA, so I better use technology,” but after that I think I realized there are so many complicated situations in technology, such as technological colonialism, the state apparatus using technology in a way to maintain control, and segregating and gatekeeping technology. I think about what it means for me to use technology in my art and how I use that technology, whether I’m using technology to make the space accessible or to make something distanced from normal people that are not tech-savvy. It’s a choice that I needed to rethink and needed to investigate. That propelled me into this program of discovering how much technology we are conditioned on that we are not aware of in life, such as surveillance eavesdropping.

In many ways, Meow Wolf strikes me as an ideal space for the kind of interactions between art, perception, and technology that you investigate in your work. How did you get connected with Meow Wolf, and how do you see your work fitting into Meow Wolf’s permanent Omega Mart installation in Las Vegas?

I have an acquaintance that either worked for or had contact with someone who worked on one of the advertisements that Meow Wolf put out on their Instagram, which are usually about these imaginary products. I was very fascinated because Omega Mart is a completely constructed space, and in my studies I look at a lot of constructed spaces. On the theoretical background of the whole research, I think it’s so related to this idea of Simulacra and Simulation, which is a book by Baudrillard and highly influenced movies such as The Matrix and cyberpunk literature. According to Baudrillard, we live in the simulation already because we live in the age of media.

In an age of visuality where we only see the two-dimensional space of the TV broadcast rather than feeling connected to the truth, I think it’s super interesting because Omega Mart is something that pierces through that fourth wall in realizing that, “Okay, so if everything is fake, then why don’t we make something that is intentionally fake?” Omega Mart is something that is born in this falsehood and is reclaiming that agency to be false. I think that traces back to my whole discussion of authenticity and the facade of the digital age.

Can you say a little more about the grant you received and vectors for your work?

The grant itself is for my TIMARA exhibition, called The Sentient Bedroom. It’ll be part research paper and part installation artwork. It’s a room full of these objects that are either functionally or conceptually sentient — objects that have sensory input and output. There is a book that breathes when it’s opened and words show up on the leather only when being touched, a bed that deflates and inflates on different speeds according to the audiences’ proximity, a chair that changes its own temperature and the light of the room when being sat on, a moving painting in a small frame, and a talking plant. I’m currently working on the chair, which is made with these stretch-sensitive rubber cords, so when you press the cords or extend them when you sit on it, they will send a signal to the central control board that will then change the ligh and possibly the ambiance of the room.

There’s a work called “I Am Sitting in a Room” by Alvin Lucier — early experimental music that is basically Lucier sitting in a room saying, “I’m sitting in a room,” and then that sentence is getting feedback or reverb from the room until eventually that feedback becomes the only thing you hear. The room itself becomes the music maker. So, the plan is a spinoff from that: different objects that have their own will and will try to exert their control onto you. They know you from you sitting on them and from the light sensor and temperature sensor and proximity sensor that’s on them. The grant mostly funds getting materials, and it also funds travel to Las Vegas to talk to Meow Wolf to learn more about their ways of doing similar things.