Oberlin Opera Theater Excavates History in World Premiere of Alice Tierney

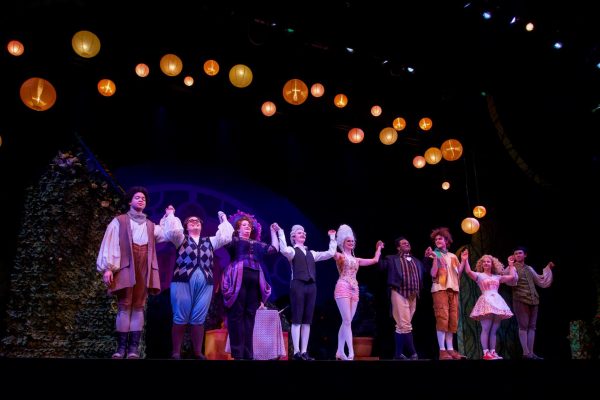

Vocal Performance students perform within a makeshift archaeological dig site on the set of Alice Tierney in Finney Chapel.

Archaeology provides little in the way of instant gratification. The work is slow, meticulous, and complicated — even as it builds to an eventual payoff. In many ways, creating an opera is the same. For the past two years, Oberlin Conservatory has become its own kind of archaeological dig site, hosting a number of workshops that allowed composer Melissa Dunphy and librettist Jacqueline Goldfinger to bring Alice Tierney to life.

The duo’s collaboration culminated Jan. 27, 28, and 29, with performances directed by Assistant Director of Opera Theater Christopher Mirto and conducted by Benjamin Martin, OC ’22. The efforts to develop and stage the opera’s world premiere were made possible by the Oberlin Opera Commissioning Program, funded by Elizabeth and Justus Schlichting, OC ’71. While Alice Tierney wasn’t the first Winter Term opera to benefit from the program, it was the first to be commissioned from scratch, with Oberlin students and faculty involved every step of the way.

The opera’s connections to archaeology are more than metaphorical, as the story centers on four archaeology students excavating the former home of Alice Tierney. A real woman who lived in colonial Philadelphia, Tierney died under mysterious circumstances — found hanging by her own petticoats — yet her death at the time was ruled an accident. However, the group’s assumptions about who she was reveal less about Tierney and more about themselves.

Take Alice 1, the interpretation of archaeologist John, played by fourth-year Jon Motes, and the epitome of the male fantasy. Dressed in vivid red, fourth-year Mae Harrell brings Alice 1 to life by playing up her promiscuity — every bit the “dissipated woman” John imagines. Like the majority of her fellow cast members, Harrell has been involved with the project since its first workshop in fall 2020. She’s been singing the role of Alice 1 the entire time.

“It’s empowering, in a backwards way, to take on this stereotypically problematic image of a woman and really get to spell it out for the audience that this is wrong,” Harrell said. “Women are more than just bodies and more than just objects for men.”

Quinn, played by third-year Jordan Twadell, interprets Alice as the polar opposite of John’s portrayal. She imagines Alice 2, played by fourth-year Kylie Buckham, as a liberated, empowered suffragist. Ultimately, however, Quinn’s version is just as much of a fantasy. In their desperate search for certainty, the two researchers blur the lines between truth and fiction. Could someone create an Alice that still acknowledges what they don’t — or can’t — know?

That responsibility falls to Zandra, played by fourth-year Kayleigh Tolley, whose version leaves room for that uncertainty. A woman dealing with a lot of emotional baggage, Zandra is in the early stages of a relationship with fellow archaeologist Lyra, played by third-year Elizabeth Hanje.

“I don’t make any strong conclusions,” Tolley said of her character’s narrative journey. “I bring the point of view that we need to look at the facts and not put ourselves into our interpretation of Alice, because that’s what all the characters kind of do.”

Zandra’s, and by extension Lyra’s, interpretation — Alice 3, played by third-year Wooldjina Present — makes her entrance in dark clothes and a black veil.

“She’s the most mysterious because we’re not defining her,” Tolley said. “We’re making space for her in the unknown.”

Onstage, the three Alices spend a lot of time observing the dig site from above, perched on the scaffolding in the back of the stage. The careful thought behind their silent reactions is one example of the transition from score to stage, spearheaded by Mirto, lead dramaturg Julia Bumke, and institutional dramaturg and Assistant Professor of Musicology James O’Leary.

“I really liked inviting everybody into the process of creation,” Mirto said. “Not being a dictator about vision and style, but rather allowing the best idea, the strongest idea, to kind of bubble up to the surface. That way, everybody has a lot of ownership over the story that we’re telling.”

Harrell spoke positively about the collaborative process, particularly working closely with the composer and librettist.

“It was empowering because a lot of the hierarchies that you find in a lot of classical music — and especially opera — were not present in those rehearsal spaces,” Harrell said.

Tolley agreed with Harrell’s assessment.

“It’s really nice to feel so respected, cared for creatively, and listened to, even though we’re young students,” Tolley said.

Workshopping and premiering a new opera is a big task for any institution — and it’s almost unheard of at the undergraduate level.

“No major undergrad institutions or conservatories that I know of are commissioning new work at this level, with undergrads fully engaged throughout the process,” Mirto said.

The journey for this cast extends beyond Oberlin, with plans to perform the work at Opera Columbus in April. No matter where Alice Tierney goes next, these seven Oberlin students will remain a permanent influence, as the creative team tailored the work to its original performers.

“It’s a female-driven cast, it’s short, it’s in English,” Harrell said. “The music is accessible, the stories are relatable — all things that I think opera needs and is exciting to see coming to life here.”