Scott’s Oberlin Experiment Leaves Complicated Legacy in Athletics

Photo courtesy of Associated Press

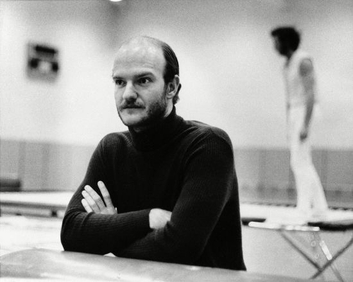

Jack Scott had a controversial stint as Oberlin’s Athletic Director.

Amid unrest after the Vietnam War, one of the societal values that was called into question was a term known as SportsWorld, the idea that sports were known for sacrifice and honor, coined by journalist Robert Lipsyte. From the arrest of Muhammad Ali to the 1968 Mexico City Olympics protests, more people were interrogating this belief.

Jack Scott was one of these people. A runner for Stanford and Syracuse University and a Ph.D. candidate from the University of California at Berkeley, Scott had a radical philosophy that advocated against traditional views of competition in favor of breaking down boundaries for non-white athletes and women, as well as calling out the financial exploitation of college athletics. Scott was influential in the world of sport sociology, writing two books titled Athletics for Athletes and The Athletic Revolution, which highlighted his ideals. He also founded the Institute for the Study of Sport and Society.

Scott was hired by former Oberlin President Robert Fuller and Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Daniel Reich in 1972 as Athletic Director. Given Scott’s lengthy legal history beforehand, his hiring was controversial, and the only endorsement he received from other faculty members was from Frederick Shults, the soccer and lacrosse coach.

Thus, the Oberlin Experiment began as Scott enacted many changes within the Oberlin Athletics department. “Reformist America: ‘The Oberlin Experiment’ — The Limits of Jack Scott’s ‘Athletic Revolution’ in Post-1960s America” by Tim Elcombe details some of his initiatives.

“Scott eliminated admission fees for Oberlin athletic events, tripled funds made available to the women’s programme, reconfigured athletic facilities and department office allocations, provided students with voting power to hire new coaches and opened the Oberlin College athletic and recreational facilities and programmes to the community,” the article reads.

Before the 1970s, Warner and Hales were separated by gender, but Scott made them co-ed spaces. He opened up the athletics facilities to the town and taught new classes such as “Sports and the Mass Media” and “Body-Mind Unity through Gymnastics.” He also hired Black coaches Cass Jackson for football and Pat Penn for men’s basketball. Arguably his most controversial hiring was Tommie Smith, who was known for his protest at the Mexico City Olympics. Smith did not have a master’s degree or much experience in coaching, which many called into question, especially because it was expected that a female coach would be his first hire. Additionally, Scott and Smith formed a committee to investigate racism and “Black needs” in the physical education department at Oberlin.

It wasn’t just Smith’s lack of experience that was controversial during Scott’s employment. Other faculty members accused Scott of attempting to force the resignations of qualified Oberlin coaches to replace them with his own. He physically assaulted a drunk 17-year-old, who required 17 stitches, there were unconfirmed charges of racism against him, and he would later use a homophobic slur to describe Oberlin’s image after he left. Finally, his promises to female athletes seemed to fall through, as he unsuccessfully attempted to convince the Ohio Athletic Conference to let women compete on the varsity level and did not hire other female coaches, while the ones he did were temporary and unpaid.

After only the first year of Scott’s academic tenure, 216 students, including Physical Education majors and intercollegiate athletes, petitioned against Scott and accused him of failing to live up to promises.

“The eight-point petition outlined three main charges leveled against Scott: the use of unethical methods to force popular faculty members and coaches to resign, overemphasizing athletics at the expense of the PE classes and a dishonest failure to implement several of the programmes promised publicly.”

An investigation was launched into Scott’s teaching in August 1973. This was only made worse by Fuller’s resignation on Feb 2, 1974. Only a couple months later, he was forced out of his position only having served one-and-a-half years of his four-year contract, which was bought out.

To this day, Scott’s legacy and work at Oberlin remains complicated. He and some of his hires were influential — Tommie Smith would teach Sociology and coach track at Oberlin until 2005 and Cass Jackson would lead the football team to a winning season in the 1974–75 season. But he was also known for intimidating others and going against his philosophies to do so.

“In death, as in life, Jack Scott remained a paradox. Scott preached freedom, but practiced tyranny,” Elcombe wrote. “He sought to return humanity to sport, but many accused him of using dehumanizing practices to belittle his non-supporters. Scott championed the inclusiveness of sport, yet was charged with ignoring sports, demonizing dissenters from his vision, and respecting only sycophants.”

Ultimately though, despite the accusations leveled against him, Scott insisted that Oberlin wasn’t ready for his change.

“My only complaint is that Oberlin tries to say it is different than other schools,” he said. “It isn’t. The school is living on its reputation, a 150-year-old reputation that goes back to its founding when it admitted women and blacks. How long can you live on your past?”