Oberlin’s Missionary History Inseparable From Current Institution

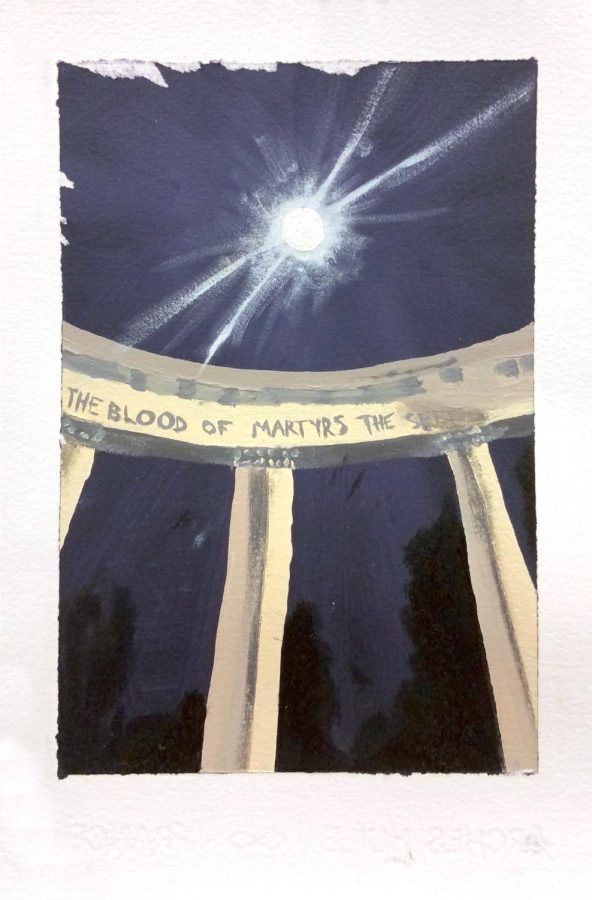

The memorial arch in Tappan Square was originally dedicated to Oberlin-connected missionaries who died in the Boxer uprising of 1900.

Oberlin College’s goals and philosophies have seen a drastic evolution in its 190-year history. At the time of the College’s founding, the United States as a whole was focusing on westward expansion and the idea of Manifest Destiny. Oberlin Collegiate Institute, as Oberlin was called until 1850, was quite literally founded for the purpose of educating and training missionaries. According to the College’s own website, founders Reverend John J. Shipherd and Philo P. Stewart established the institution to “train teachers and other Christian leaders for the boundless most desolate fields in the West.” Beyond just being a college, Oberlin was founded as a “colony” that was to be led according to its founders’ Presbyterian beliefs.

“There’s a longstanding history here of Oberlin people going to foreign lands or other parts of the country,” College Archivist Ken Grossi said. Oberlin-educated missionaries traveled to Minnesota as early as 1842 “to work among the Ojibwe Indians,” according to the College Archives. Oberlin’s missionary history in Asia began in the 1880s when a group of Oberlin-educated missionaries known as the “Oberlin Band” volunteered to serve as missionaries to China.

The Memorial Arch in Tappan Square is a physical remnant of Oberlin’s missionary history in China. Its dedication plaque reads that the memorial “was brought into being by friends of the Oberlin-connected missionaries who lost their lives in the Chinese Boxer Rebellion of 1900.” Large plaques on either side of the walkway through the arch list the names of those killed under- neath the word “massacred.” It was commissioned by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, an organization based in Boston, and serves as a memorial to all American missionaries who lost their lives in China in the Boxer Uprising, not just Oberlin-educated missionaries. However, Oberlin was chosen as a location because almost all of the missionaries killed had been educated at Oberlin.

The arch has been a source of controversy on campus for quite some time. Prior to 2009, Oberlin’s annual commencement path had graduating students walk underneath the arch. It was not uncommon for students to walk around the arch in protest of what the monument stands for.

“The arch used to intrude on people’s consciousness once a year when it was involved at commencement, and people had to decide how they felt about it,” Professor of Art History Erik Inglis, OC ’89, said.

According to Inglis, the tradition began as early as the 1950s and continued until commencement ceremonies were relocated to a different part of Tappan Square in 2009.

Oberlin’s missionary history does not only linger in physical monuments on campus. Inglis considers the College’s present-day emphasis on the individual — for instance, the motto of, “Think one person can change the world” — to be reminiscent of missionary rhetoric.

“I think the marketing motto ‘Think one person can change the world? So do we,’ resonates with a missionary ethos,” Inglis said. “That idea — missionaries go out to change the world, to convert people — Oberlin is encouraging people to think about changing the world, so those two resonate together for me.”

Grossi said that in the College Archives, these connections are embraced and sought out.

“We try to make connections with the early history,” Grossi said. “When you learn about our history and about those people that were going out and being activists in whatever cause they were devoted to, that kind of translates to what we might do now.”

There are also programs that are legacies of Oberlin’s missionary past. The Oberlin Shansi Memorial Association was founded in 1908 with the purpose of supporting education at the Ming Hsien School in Taigu, Shanxi Province, China. Its original constitution reads, “It shall be the purpose of this organization to perpetuate the memory of those who suffered martyrdom in 1900 in the Shansi field, by promoting in every feasible way… the educational work in connection with the Shansi Mission in the Province of Shansi, China.”

Shansi’s legacy has continued to this day. One of its main programs is the Shansi Fellowship, which, according to their website is “for recent Oberlin graduates to teach or engage in service projects at partner institutions in Asia.” While the program no lon-

ger includes religious teachings, it is still a legacy of Oberlin’s missionary history.

“I think even today, when our students go out as Shansi reps, for example, they go to China, they go to Japan, they go to other places around the world,” Grossi said. “They might be going there to teach English, but they’re also learning about the culture. They’re really carrying on that service that really is rooted in the history that goes back to the 19th century.”