Conservatory Instrument Collections Reflect Stories, Research, Interests of Faculty

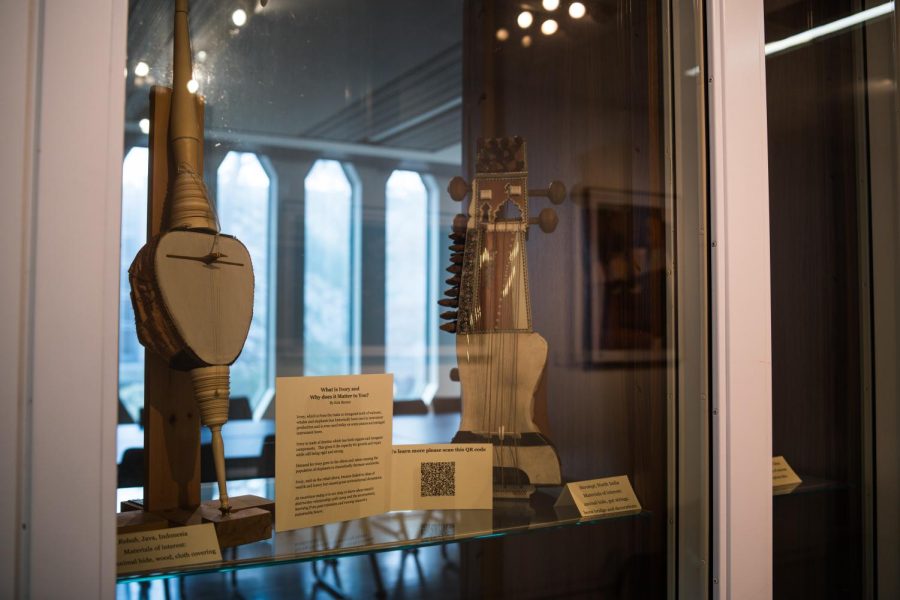

Instruments from The Roderic C. Knight Musical Instrument Collection are displayed in Bibbins Hall.

Oberlin’s collection of instruments is dispersed throughout Conservatory buildings, like Bibbins Hall and the Kohl Building, in display cabinets and storage facilities. The relationship that the Oberlin community can have with these culturally and historically significant instruments is thanks to two former Conservatory faculty members and collectors Frederick R. Selch and Roderic C. Knight, after which the two collections are named.

The objects of the Roderic C. Knight collection were donated by Professor of Ethnomusicology Emeritus Roderic Knight following his retirement in 2008. Knight started collecting instruments as a high school student and continued to do so as he traveled and worked with different styles of music all over the world.

“I was a professor here for 32 years, teaching classes on the music of pretty much all parts of the world,” Knight said. “My hope was that I could play a recording whenever possible, although this was before the internet was readily available. I didn’t always have a visual for everything I played in class, so I was eager during my career to acquire actual instruments that I could take to class and say here it is, this is what you’re hearing. Whenever I was traveling and doing research, I was always interested in acquiring instruments for that purpose. Sometimes I was also buying instruments with money provided by the Conservatory to be used for performance, or, I should say, for teaching and learning to play those instruments.”

Aside from collecting instruments for students to view, some of the instruments in Knight’s collection were acquired for students to actually learn how to play.

“What typically happens is someone is interested in an instrument and discovers that we have one and then I can make it available,” Knight said. “Usually this is a student who knows about an instrument or maybe has studied it a little already and wants to continue practicing. My own specialty in my career was the instrument called the kora. I came to Oberlin with my own collection of three or four of these instruments. And I began teaching one of the Applied Studies courses in non-Western traditions called the Mandinka Ensemble, the name of the people in West Africa whom this music comes from. In 1986, I went back to Gambia and I bought six instruments for that ensemble, and now, individually, people can borrow a kora and play it. I actually will teach students on that instrument.”

Some of the instruments in the collection are not originals but rather models of instruments that might not otherwise be available to students and were unable to be acquired by Knight. Other instruments in the collection were donated by community members once the Conservatory formally established the Roderic C. Knight Musical Instrument Collection.

“When I retired, I decided that I wasn’t going to take all of these instruments that I’d been taking to class home, I was going to leave them in the Conservatory,” Knight said. “Once the collection was established and we had this catalog up online, other people began to give instruments to the collection.”

The other part of the Conservatory’s armory of historic instruments is the Frederick R. Selch Collection of American Music History. Selch’s family donated his collection of around 6,000 rare books and music manuscripts, as well as nearly 700 instruments to Oberlin after he died in 2004.

“[Selch’s family] wanted to make sure that his collection was not just going to be stored in a large museum where nobody would probably see it, but somewhere where it would appear in the classroom,” Frederick R. Selch Associate Professor of Musicology James O’Leary said. “So that’s what we do at Oberlin, we take these objects out, we let students use them, we bring them into classes.”

The objects in the Selch collection span from the early 16th century to the late 20th century and reflect Selch’s own specific musical interests. Selch’s specialty was in 17th and 18th-century church basses which were used in the American colonies.

“For a long time, nobody quite knew what these instruments were about,” O’Leary said. “You know, in the churches of the time, especially the puritanical sects, there were no instruments. So what were these instruments doing there? Eric believed that they actually were used in some churches in a very limited vein. These instruments are fascinating. They’re strange looking, broad, and weirdly shaped, made of all kinds of different woods with different features on each of them. So they look strange, but on the other hand, they kind of elude classification. So they’re cello-like but not quite. They’re historical oddities. They’re really interesting. And we have a bunch of those in various conditions, some can be played, some are only in pieces and [Selch] collected those and wrote a dissertation about them.”

Unlike the instruments in the Roderic C. Knight collection, many of the Selch objects are fragile, and not necessarily playable. This introduces the question of conserving these objects.

“In the world of collecting, there have historically been two sides that don’t agree with each other,” O’Leary said. “There’s the historical preservation side and the restoration side. Historical preservation wants you to keep the musical instruments or books or whatever in the condition they are right now and not allow them to decay further. The restoration side will fix up the instrument, take the broken parts off and remake new ones in order for it to be usable again, in its former glory, you might say. Now, you can imagine to somebody historically minded the restoration looks like destroying history. For somebody who’s restoration-minded, they see that the spirit of the object was to be used, and we’re not using it, we’re just looking at it.”

This conflict in our own collection reflects a debate being held in nearly every institution in possession of musical instruments. Stewards of historic instruments have a responsibility both to maintain the history of the objects and their musical purposes. Although current efforts are being made to conserve the objects in the Selch collection, O’Leary has hopes for the expanded reach of these instruments and objects of musical history in the future.

“On the one hand, this is a conservatory, so I want as many of these instruments as can be used to be used, as long as they’re valuable for students and as long as they produce a sound that will be useful in the Conservatory,” O’Leary said. “On the other hand, these instruments are fascinating and just looking at them helps us know our own instruments better. So I would like them to be seen more. I’d love for them to reappear in the [display] cases around campus. I’d love for classes to get back [into the collection]. We’ve also been working on cataloging the collection for a long time, and I’d love for us to be able to get them online so that people from outside of Oberlin can know what we have and work with these objects.”