From an early age, I was obsessed with Stephen Sondheim. Known as the father of 20th-century musical theater, his works are widely acknowledged to have redefined musical theater as a genre. My childhood bedroom is full of scores ranging from Company to Into The Woods, and I used to listen to each cast recording hoping to be in a performance one day. Part of the reason I went to Oberlin was its many notable musical theater alumni like Judy Kuhn, OC ’81, and Natasha Katz, OC ’81. This is why I became interested in taking MHST 420, taught by Frederick R. Selch Associate Professor of Musicology James O’Leary, which focuses on Sondheim’s major works and collaborations with other artists.

“Classmates once a week look at one show,” O’Leary said. “We generally focus on a part of a show and talk about what’s going on in it. What I tell people when they first join the class is to check it out for the first week or two and see if this is a level in which you feel comfortable operating. But in my heart of hearts, it’s a course that’s open to anybody who wants to engage with Sondheim’s music and scripts and scores at a deep level, to analyze what the shows are, how they work, what they have meant to people in the past, and what they mean to students now.”

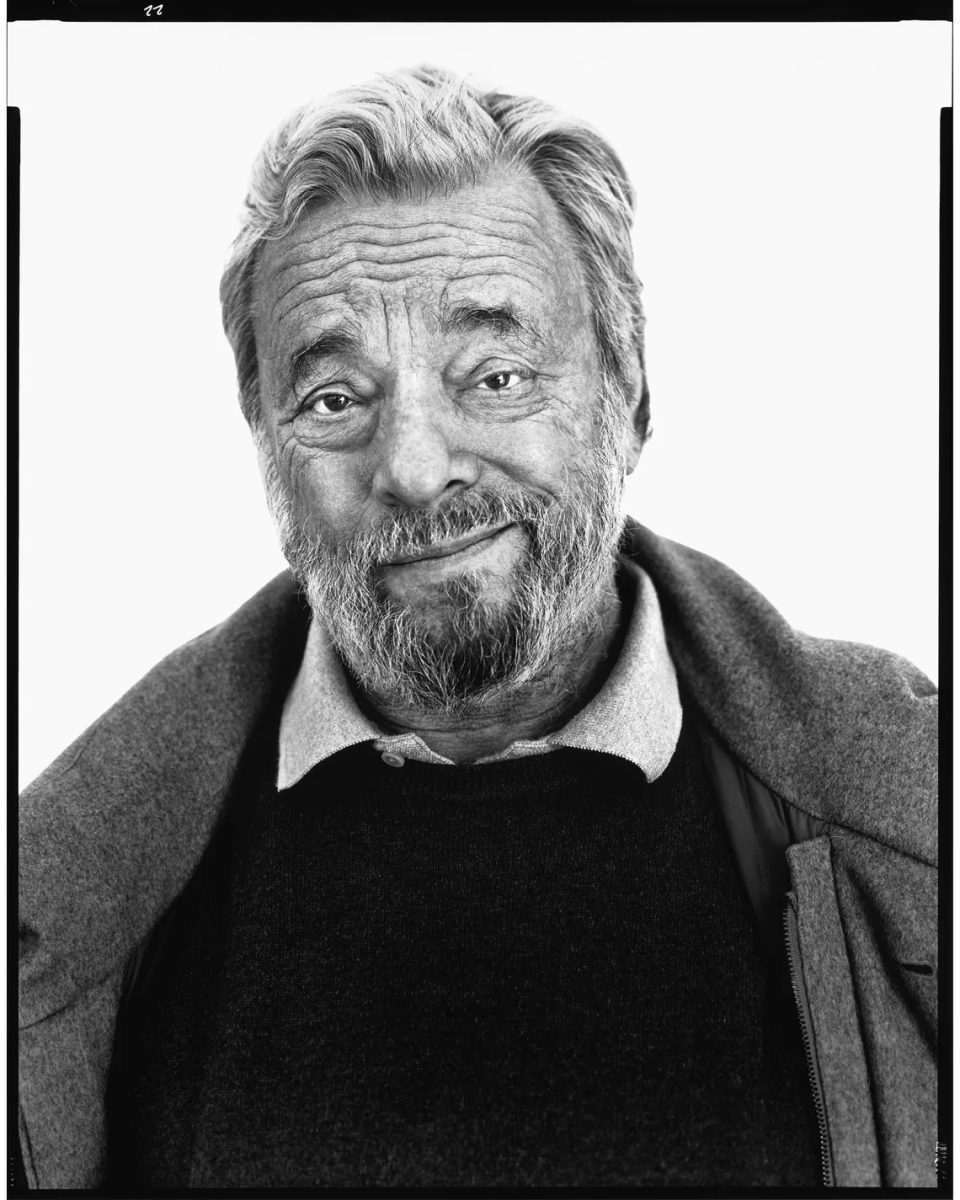

Sondheim was born in 1930 and went on to forge friendships with many Broadway lyricists and producers, including his mentor Oscar Hammerstein II, creator of Carousel and The Sound of Music. Sondheim created many famous musicals still being produced, such as Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street and Sunday in the Park with George. Sondheim won dozens of awards, including eight Tony awards, eight Grammy Awards, and an Academy Award.

“American theater is kind of a niche field,” O’Leary said. “Not a ton of people had been working in it until recently. It seemed like a sideshow to international theater studies. But what I’ve uncovered in my research on [Sondheim] — I’m going through his archive, letters, scores, and scripts — I discovered that Sondheim is a figure who’s trying to bring international theater debates to the Broadway musical in the middle of the 20th century. Sondheim gives us a way to think about how Americans filter international theater trends in the middle of the 20th century. He starts by getting involved in this kind of theater called metatheatre, which was represented on Broadway by a small group of French and Italian plays. Metatheatre portrays the world as theatrical, such that our everyday lives … hide the nasty society underneath.”

One of the first questions I asked Professor O’Leary was whether or not students are required to have an understanding of music theory to participate in the class. While I keep many Sondheim scores with me, there is only so much I can understand without formal training. O’Leary responded that it is very beneficial for students to have some level of music theory training, but Conservatory and College students alike enroll in the class, making the most essential prerequisite a love for Sondheim and an understanding of his scores. Sondheim scores are often cited as having brilliant lyrics, with deeper meaning and messages embedded into the musical notation. Students work each week to examine that notation and explore how Sondheim pushed the boundaries of conventional musicals.

“It’s supposed to be an introduction to graduate-level studies,” O’Leary said. “So throughout the course, I have the students do this kind of literary review. I’ll give them a topic within the genre of musical theater history or Sondheim studies, and I’ll give them a few different scholars talking about the same thing and ask the students to pick out the subtle differences between them. And sometimes, it’s hard to see exactly where they differ. And then their job is to investigate why we think of Sondheim when listening.”

Professor O’Leary and I bonded over our shared love of Company, his favorite Sondheim musical. Listening to the album as a kid sparked a fascination with Sondheim in both of us that has lasted to this day. Through this class, Professor O’Leary hopes to celebrate Sondheim and pay homage to his work.

“I can take something that students have a lot or some kind of knowledge of, and look into the typical narratives about Sondheim,” O’Leary said. “It’s a way to see if we can expand those out and get exposure to all these different movements throughout the semester and then figure out how Sondheim’s working his music into those theatrical genres.”