On Friday, Dec. 1, artist Julia Kwon led a collective quilting workshop in Peters Hall. Students gathered to each sew a work that Kwon plans to add to a patchwork quilt.

Kwon primarily works with the medium of textiles to comment on social issues related to her identity as a Korean-American woman. She sews quilts using traditional Korean wrapping cloth called bojagi and drapes the quilts over human-sized figures to represent the objectification of female Asian bodies. She also uses bojagi to represent sociopolitical statistics: she unapologetically bestows her artworks with lengthy titles such as “The Percentage of People Who Consider Themselves an Ally to Women of Color at Work vs. Percentages of People Who Consistently Take Specific Actions of Allyship at Work.” Kwon uses these titles to ensure that her audience cannot shy away from the issues she focuses on.

Kwon has led several quilting workshops with the intention of opening up a dialogue about gender and ethnicity.

“These workshops have been really generative for me,” Kwon said. “They feed back into my own individual work in the studio as well. Hearing from audiences and viewers and participants oftentimes renews why you’re doing what you’re doing.”

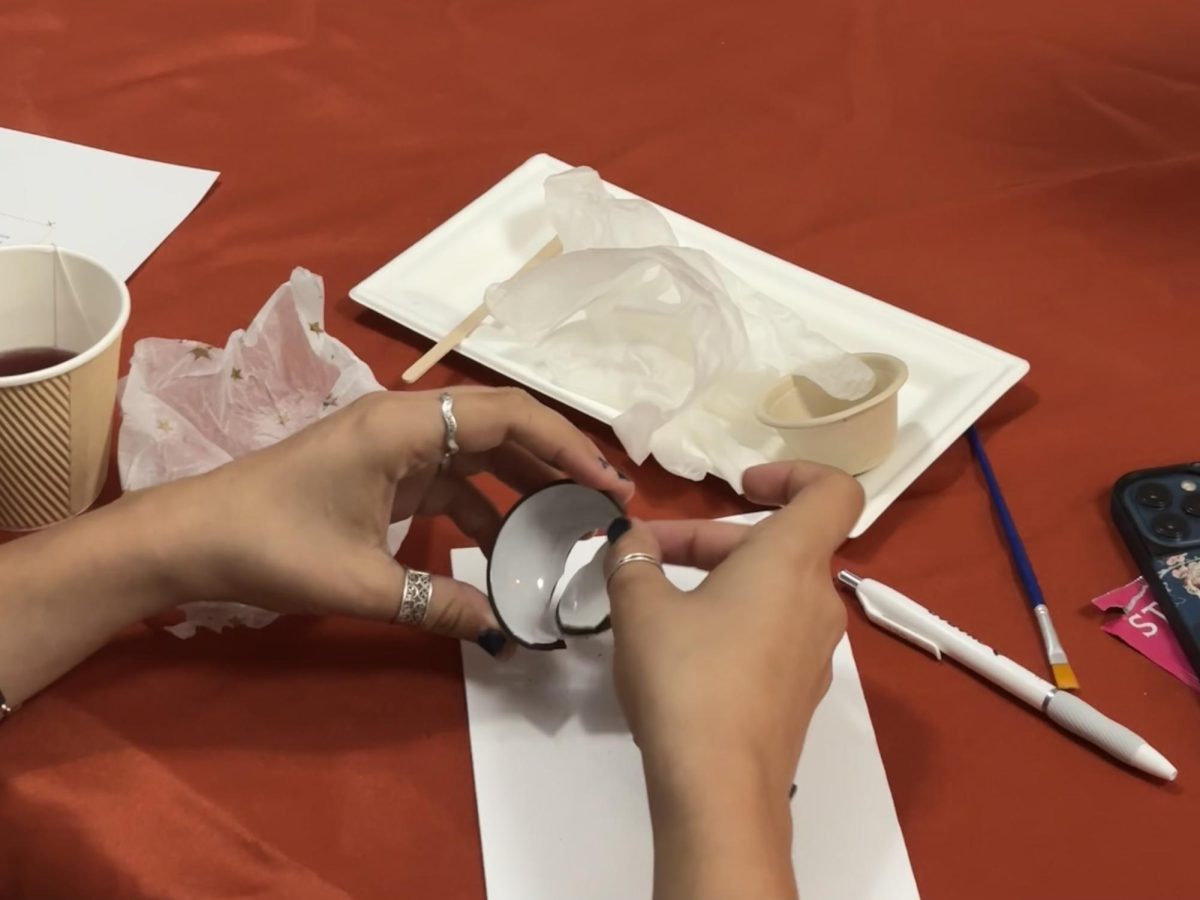

After briefly presenting her work, Kwon covered a table with a mound of fabric, needles, thread, and scissors for workshoppers to pick through. Students possessed varying levels of sewing talent. Some had never sewed before, while others had already worked on large textile projects. Despite varying degrees of expertise, students sewed comfortably in small groups, all invested in their work.

“There’s no barrier to entry,” Kwon said. “Anyone can join and learn how to sew, embroider, and create what they want to create. Anyone can contribute, be a part of this larger conversation, and stand in solidarity with others.”

The workshoppers worked on various projects.

“I thought it was a fun community event, and it was interesting to see the ways in which people used the medium of quilting,” College second-year Alee Holman-Evans said. “I deconstructed a baby tee and gave it whimsical and baby qualities.”

College second-year Ruby Spencer also enjoyed the event and commented on what they created.

“I made a little quilt piece that had a bikini top on it,” Spencer said. “It had no meaning necessarily; I just saw a piece of bikini-shaped fabric and decided that that’s what I was going to make.”

Kwon traveled across the room as students sewed, answering their questions. She discussed her artistic process and the relationship between her art and social issues. Although Kwon’s artwork takes on matters pertaining to her identity, they are meant to embody the larger group struggles her identity is a part of.

“My artwork is about putting up a mirror against how people perceive me,” Kwon explained.

Before working with textiles, Kwon was a painter. She made the switch during graduate school when she reconsidered the message prioritized in her work. Kwon realized that opening up a conversation surrounding social issues was essential to her. Growing up, she had not explicitly thought about race; however, as she aged, she was forced to confront the reality of racial relations in the United States.

Kwon used to hand sew more frequently, but as her projects became more ambitious, she began machine sewing for time’s sake. Every once in a while, though, she still hand sews. Its deliberate approach helps her process her work and the issues on her mind.

“We have such an immediate connection to fiber,” Kwon explained. “I think there is strength in using textile because of that connection, as opposed to painting.”

Her work is in the permanent collection of many museums, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; the Museum of International Folk Art; and the New York Public Library. She has received positive feedback from her immediate community and people worldwide. People of other ethnicities and from different backgrounds have reached out to Kwon, saying how much her work resonated with them.

For some people, Kwon’s work is the first time they’re confronted with such ideas. Kwon explained that this can be jarring, since she has long considered these issues. She has also experienced some resistance towards her work with textiles, although she maintains a positive attitude.

“There’s still that arbitrary hierarchy in terms of what medium is more important or what constitutes as an art medium versus just textile,” Kwon explained. “But I do think it’s changing. I think people are becoming more aware and more open.”