On April 7, 2023, The Oberlin Review published an article titled “College Ethnographic Collection Demands Increased Awareness, Reckoning with Our Colonial History.” This story centered around Associate Professor of Anthropology Amy Margaris, OC ’96, and an ethnographic collection of approximately 1,600 objects of primarily Indigenous origin. Margaris took the role of steward of the collection in 2017.

Margaris coined the term “dangling collections” to refer to these jettison objects, in that they lack formal curatorial oversight like objects in a museum may have. The issue is twofold: dangling collections often remain tucked away in storage and therefore serve little purpose, and it means that for the better part of the 19th and 20th centuries, many sacred items remain wrongfully in the possession of institutions.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act was established in 1990 to require institutions and agencies that receive federal funding and have sacred objects in their collections to report them to the federal government and return the objects to lineal descendants of their communities of origin. NAGPRA provides channels for consultative processes with Native American tribes and pathways toward repatriation of objects.

Recently, NAGPRA was amended to identify a clause that had allowed institutions to classify items and human remains as “culturally unidentifiable” as justification for keeping the items and conducting research on them. The amendment aims to expedite the process of repatriation of such objects, including one possessed by the Allen Memorial Art Museum.

On Aug. 23, the Federal Register published a notice by the National Park Service announcing Oberlin College’s intent to repatriate the object to the culturally affiliated tribe. Presently, the object is subject to a one-month holding period to allow for other Native American tribes to claim the item. The press release describes the object as follows:

“A total of one cultural item has been requested for repatriation. The one unassociated funerary object is a ceramic vessel. The vessel … is housed in the Allen Memorial Art Museum on the campus of Oberlin College and was attributed in some AMAM records as Peruvian (Chimú) in origin.”

This object — a ceramic water bottle — was gifted in 1920 by the wife of Herbert H. Wright, class of 1873. Wright was a professor of Mathematics and Music at Fisk University in Nashville, TN, and discovered the “bird-shaped vessel” in Noel Cemetery, a known Native American burial site. Wright found the object in 1885, as indicated by a torn label on the bottom of the vessel.

“When the original 1990 NAGPRA law went into effect, the Allen did go through its collections of Native American or Indigenous American works, and sent relevant information back to the federal government,” AMAM Director Andria Derstine said. “That item, because it was cataloged as Peruvian, which we’ve determined to be a mistake, wasn’t included in that.”

The piece has already been deaccessioned from the Allen’s collection. Derstine worked alongside Margaris, who also serves as NAGPRA Compliance Officer for the College, to complete the necessary correspondence for repatriation to three Cherokee tribes in the aforementioned area.

Throughout this process, Margaris and Derstine worked closely with Sundance, a member of the Muskogee people. Sundance works as the executive director of the Cleveland American Indian Movement and business coordinator for the Oberlin Student Cooperative Association, and sits on the Oberlin Indigenous Peoples’ Day Committee. He also is a fervent advocate for Indigenous self-determination, including work with repatriation and rematriation.

“What makes an item sacred, what makes anything sacred, is that fact that it has power,” Sundance explained. “And some people are just tuned to that, and I’m attuned to that, so when I get an item that’s a power item, typically I can determine power. I am also fairly versed and I have found what cultures make particular items.”

In the case of this vessel, Sundance did understand why it was initially labeled as Peruvian.

“But without asking specifically, you never really know,” he said. “[For] my people — Muskogee people — a lot of our ancient works look the same as, say, Mayan [works] — we’re descended from Mayans. So, it can get you into a ballpark but, really, the legwork has to be done. When Amy and I were talking about what type of legwork should be done, I always suggest contacting as many groups in the United States as possible.”

However, it’s paramount to note that NAGPRA only applies to organizations that receive federal funding, such as Oberlin College.

“I can understand the reason for the bureaucracy,” Sundance said. “But, [NAGPRA] seems from my perspective to be more focused on the bureaucracy than the rematriation. … I do not hesitate with engaging an institution that I feel needs some prompting, some educating, some advocacy, some instigation. Certain people are just more comfortable doing that than others. I have benefited because I was raised by Native people who had a lot of knowledge and had a certain perspective [and] raised me with the understanding that if I don’t advocate for myself, no one will and that being Indigenous is not supposed to be easy.”

While this present repatriation of the water bottle generates substantial forward momentum, a plethora of other institutions are still struggling to comply with what NAGPRA outlined three decades ago. Thousands of Native American remains, funerary objects, and sacred objects remain in the possession of institutions not unlike Oberlin. However, this story of colonial history is larger than objects — it concerns an entire population.

“We have this nascent Indigenous Student Council Group, a group of Indigenous students that have been, in previous eras, pretty invisible on campus,” Margaris said. “What I’ve come to see is so much of this work around repatriation is really about building new or mending old relationships. It’s a people to people process. The objects facilitate that, but sometimes objects are not repatriated [because] that’s not the wish of a group. What ultimately, I think, is going to help tribal groups heal from colonial era harms is feeling empowered.”

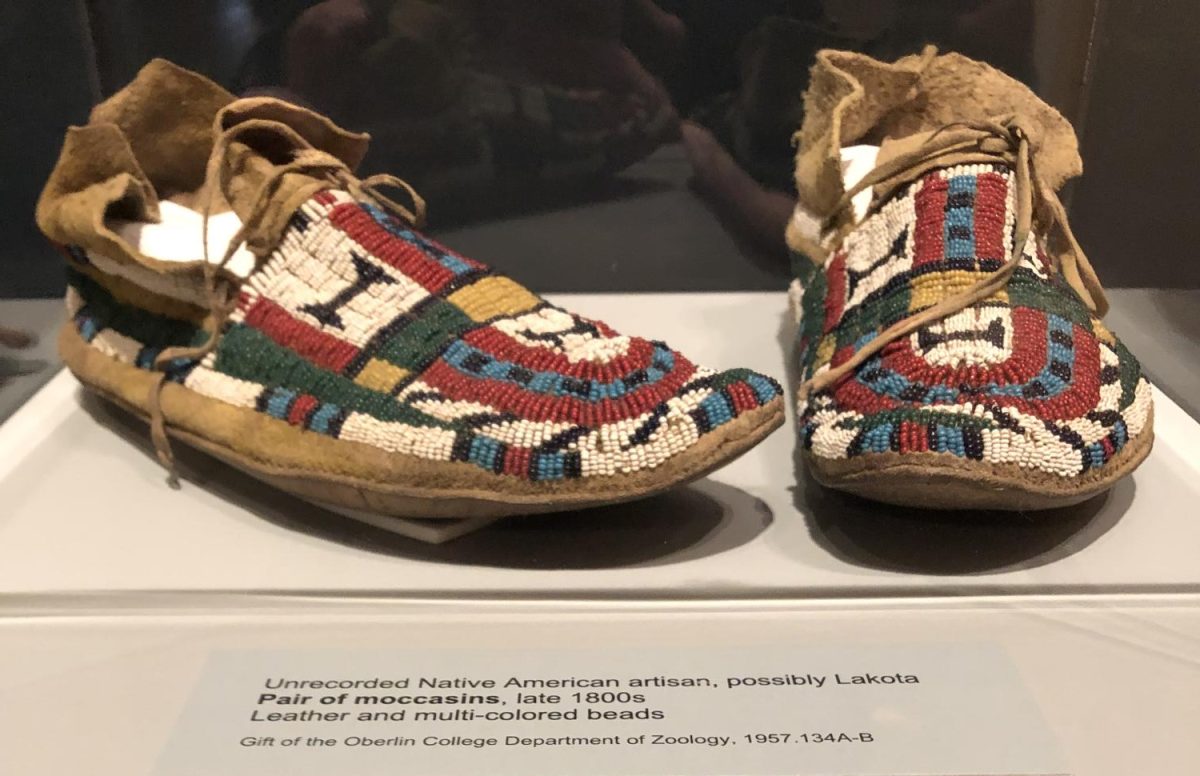

We would like to acknowledge the Indigenous people who occupy the land in Northeast Ohio, who are primarily the Choctaw, Diné, Haudenosaunee, Lakota, Odawa, and Ojibwe nations.