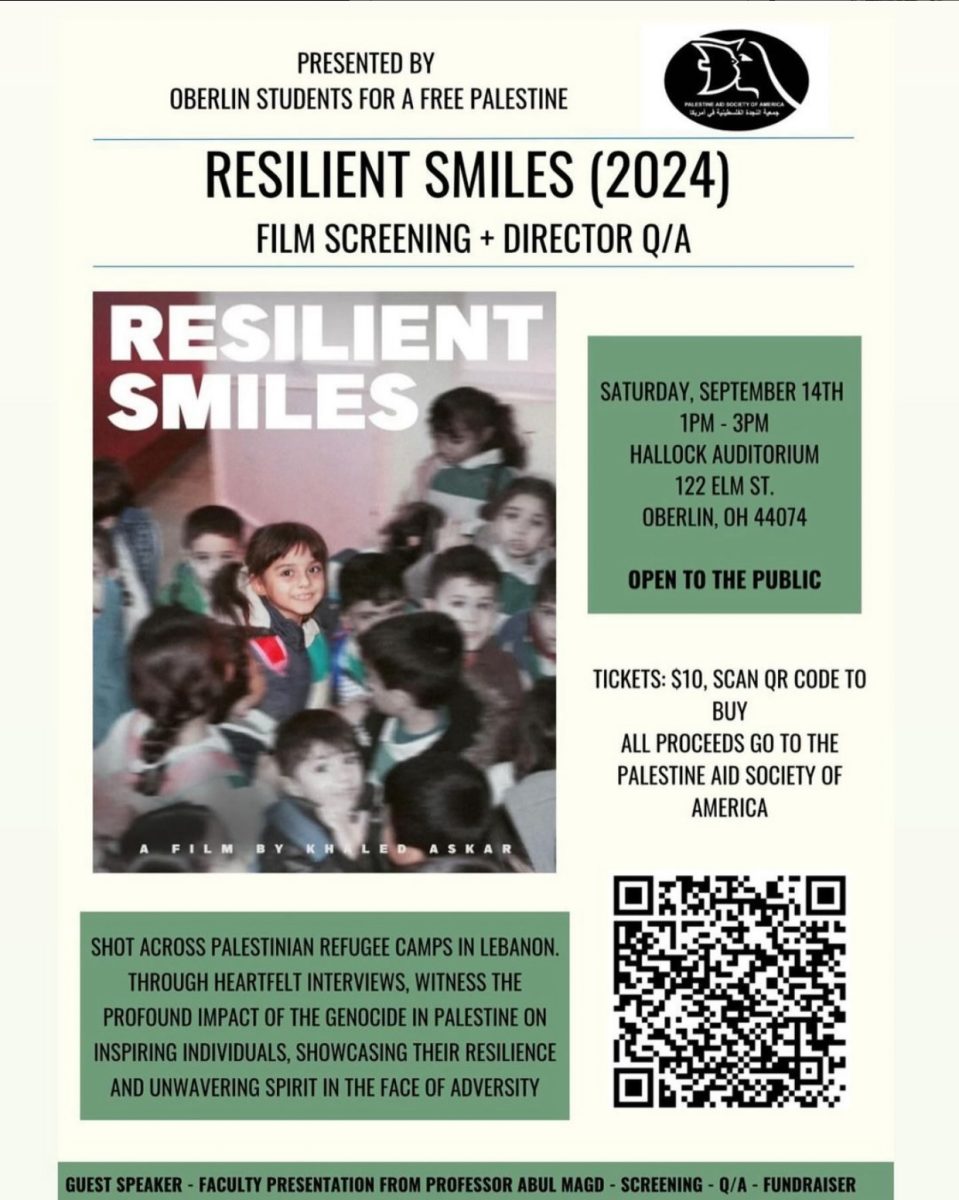

Last Sunday, I attended Students for a Free Palestine’s film screening of Resilient Smiles, made by third-year undergraduate student at Cleveland State University Khaled Askar with a one-person crew. The film tells the story of life in the Bourj el-Barajneh displacement camp in Lebanon. Askar highlights life for displaced Palestinian children, filming moments of learning and joy within various preschools there. The film is powerful. It juxtaposes scenes of destruction from airstrikes, dangerously exposed wires, and abject poverty with raw footage of residents who share their stories about their original homes in historical Palestine in their own words. In these stories, it is clear that their sense of belonging remains steadfastly connected to these original homes despite the multiple generations within these families who remain displaced. Askar’s film centers the pockets of joy in everyday life in Bourj el-Barajneh and, ultimately, the unrelenting hopes and dreams of these Palestinian families returning home. This hope of return comprises a fundamental facet of their identities.

Askar, a health sciences and predental student who had no prior filmmaking experience save a high school photography class, serves as a powerful example of how activism for social justice can materialize in unpredictable and unconventional ways. Being half-Palestinian and half-Lebanese and born and raised in the U.S., Askar noted that Hamas’ Oct. 7 attacks and the near-yearlong assault that followed served as his call to educate himself on the political history of Palestine.

“I never really learned on my own about the history of the region, or about the past 76 years,” Askar said.

After seeing the footage of the destruction wrought on Gaza following Oct. 7, he reached out to numerous NGOs involved in delivering humanitarian aid to various UNRWA camps, both in Palestine and the surrounding areas where Palestinians had fled. Askar’s outreach efforts paid off when the Al Najdeh Association — a sister organization to the Palestine Aid Society — offered to bring him along on a tour of various preschools within the Bourj el-Barajneh displacement camp. In these tours, the folks of Al Nadjeh Association educate young children on the importance of dental hygiene. Askar’s process of filming was unplanned — he shared that he actually forgot to bring his camera set on the plane with him to Lebanon. But the film’s story shows that spontaneity can yield something quite beautiful.

When talking to his family the day before leaving for Lebanon, Askar explained, his cousin suggested he take a costume of some sort to entertain the preschool children. Though he didn’t bring the camera, he remembered perhaps the most important thing — his extra-large Spiderman costume. Throughout the film, masked as the iconic, friendly neighborhood Spiderman, Askar silently demonstrates to the children how to properly brush their teeth. There is a powerful message that Askar conveys through these acts. In every moment where he enters the room in his disguise, the film shows the children filled with excitement. On several instances they rush Askar, attempting to pull his mask off.

“These children don’t want to be forgotten,” Askar said. “You have a soft heart for those children. … After [Oct. 7], I thought to myself, ‘What if I was in their shoes, what if I was reaching out for a hand and no one was there?’”

He showed the children — and perhaps the adults, too — that there were people around the world willing to reach their hands out in return.

The film includes several interviews with displacement camp residents. All of the residents explain that they are multiple generations removed from their original homes in historical Palestine. Lebanese law and regulations forbid the majority of these residents from leaving the territory of the camps, so an overwhelming majority of them have never even stepped foot on Palestinian soil. Despite this, the film shows that their identity with Palestine remains strong and uninterrupted.

“Every little thing has a meaning, from naming children after Palestinian villages, performing cultural dances, and traditional arts,” Askar said.

They routinely cultivate and preserve their connection to Palestine through everyday activities. As the descendants of people who originally thought they were fleeing to camps like Bourj el-Barajneh just for a couple days or weeks following the Nakba in 1948, it is common practice for households to still keep the keys to their original homes. In the interviews, children as young as six years old tell the stories of what life was like in Palestine for their grandparents and great grandparents. This powerfully illuminates the fact that these Palestinians’ basic humanity and their longing for return cannot be extinguished, no matter how brutally assaulted they are. Though the majority of the buildings in Gaza have now been leveled by Israeli airstrikes, the vision of Palestinian society can never be destroyed as long as these people — who carry the stories, traditions, and memories of those who lived before them — are standing.

The film issues to us a direct call to action. It asks us to do whatever we can to ensure that these displaced Palestinians remain standing and gives us a model for what it takes to sustain their hopes for return to their former lives of dignity. Askar said that he wanted to show audiences in America the scenes of desecration that the residents live among on a daily basis. He wanted to share the stories he recorded with us so that we can in turn raise awareness and share those stories further. He also said that the most basic act people can do to keep the vision of Palestine alive is to donate, and implored anyone with the money and ability to do so. The Palestine Aid Society that Askar has been partnering with has been in operation since 1978. 100 percent of all donations they receive go toward immediate aid related to health, food, and other services that Gazans and Palestinians urgently need.

Despite the somewhat chaotic process of the film’s creation, Askar’s project has ensured that these Palestinian voices proliferate. It is a crucial role of direct action in the movement for Palestinian liberation. In turn, it calls for us to work to ensure that these Palestinian voices continue to be heard by spreading their stories, donating to humanitarian organizations, or creating our own projects.

“There’s no strict definition that art is confined to,” Askar said. “I encourage people to keep finding their niche in order to make a difference.”