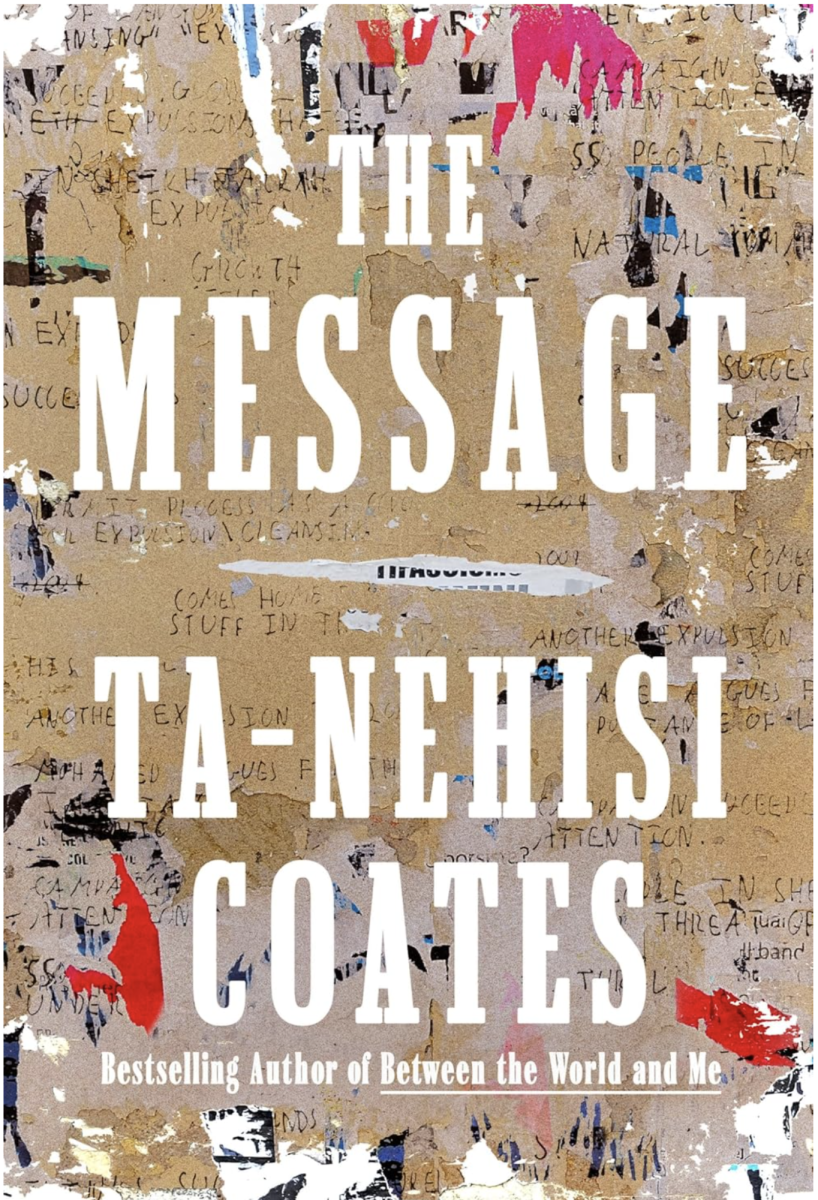

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates was a highly anticipated release in my community, both at home and within the Africana Studies department. I first heard about it from professors and fellow Black students, many of whom eagerly awaited its arrival. Coates had already made a profound impact on me when I read his book Between the World and Me during my first year at Oberlin. I was captivated by the way he described race in the United States and found it powerful how the book was framed as being addressed to his son. The Message is similarly structured, this time directed at his students in a class he taught at Howard University. When I discovered this, I immediately pre-ordered a copy. It is no surprise that after its arrival, I devoured it over fall break, finishing within just three days.

The Message takes readers through Coates’ journeys all over the world, recounting his experiences in places like Dakar, Senegal; Columbia, SC; and Palestine’s West Bank. Each location is a springboard for reflecting on topics such as white supremacy, colonialism, and what it means to be a Black writer today. Above all, the book is a call to action for his students, urging them to see writing as a powerful tool for change by connecting his own observations with global liberation efforts.

In the section on Dakar, I found Coates’ writing to be not only inspiring but also deeply relatable. He describes his journey to Senegal as his first visit to Africa and shares his feelings of awe and connectedness with a land that, though unfamiliar, is tied to his heritage. Similarly, while at Oberlin, I went on a trip to Egypt that sparked a sense of reconnection to a culture and history that I had previously felt distant from. Although Egypt differs from Senegal demographically, I resonated with the sense of pride and belonging that Coates describes. Coates has a remarkable ability to convey the excitement of experiencing new places, making readers feel as if they are walking through foreign streets alongside him. He does so by highlighting the warmth and hospitality of Dakar’s people, from merchants inviting him into their stores to a young writer who admired his work. Travel, he argues, can deepen one’s understanding of self and history in ways that are crucial as an author. He emphasizes how traveling to Africa can affirm a sense of identity for Black Americans, reconnecting them with an ancestral homeland. For Coates, this journey underscores a broader message: as Black people and as writers, we have a duty to honor our past and our heritage.

He also explores how colonialism impacts this connection to heritage, noting that elements like Western beauty standards affect Black people worldwide. While disheartening, this shared experience also strengthens the global solidarity among people fighting against white supremacy. Coates sees this shared struggle as a source of strength, connecting Black communities around the world who face similar challenges despite geographic separation.

The book then shifts to Coates’ experience in Columbia, where his book Between the World and Me was facing the threat of censorship. Here, he met and built a relationship with Mary Wood, a teacher who had been struggling to keep the book in her curriculum amid growing resistance from school administrators. This struggle is set against the backdrop of a larger movement to ban educational resources that address race and challenge white supremacy. Coates uses this story to highlight the power of history and literature in shaping young minds, as well as the fear of this power among those who wish to suppress it. He asserts that books like his challenge narratives that uphold white supremacy, posing a threat to those invested in maintaining such structures. Through detailing the resilience of Wood and the courage it took to teach his book, Coates stresses the power of the pen in challenging injustices. As an aspiring writer myself, I found this section particularly inspiring. Coates reminds us that writing is a powerful tool in the fight for social justice, evident in the fierce opposition writers face. This part of the book goes beyond race, showing that the journey toward liberation requires collective effort regardless of one’s background. Coates suggests that everyone, whether they are a white teacher like Mary Wood or a Black writer like himself, has a role to play in dismantling systems of oppression. The theme of solidarity he establishes in the Dakar section reemerges here in South Carolina, bridging the importance of honoring Black heritage with the need to protect Black stories from erasure.

In the final section of the book — the part most anticipated by readers, myself included — Coates takes readers to the West Bank. Coates draws parallels between the treatment of Palestinians under Israeli occupation and the experiences of Black Americans under Jim Crow laws. He makes it clear that, despite there being similarities, their histories and present day crises are distinct from each other. Coates describes Israel as a nation founded to protect those who had been persecuted, only to later adopt systems of control that mirrored those they had once suffered under. His accounts of the harassment, surveillance, and violence Palestinians face paint a harrowing picture, highlighting the urgency of the Palestinian struggle. Coates connects with Palestinian writers and activists during his stay, reinforcing his belief that true liberation must be universal. He emphasizes that the suppression of Palestinian voices is a significant barrier to justice, as their stories often go unheard on the global stage. Coates uses this experience to broaden the line of solidarity he has drawn from Dakar to South Carolina to the West Bank, demonstrating that the fight against oppression is global and interconnected. The Palestinian struggle, the struggle to protect Black stories in America, and the journey to reclaim one’s heritage in Africa are all bound by a commitment to fighting against systems that oppress and devalue peoples’ culture, heritage, joy, and lives.

Through The Message, Coates speaks directly to his students — and to anyone who considers themselves a writer — about the importance of documenting truth. In an era when traditional platforms for writers are declining, he argues that writing still holds immense power. Coates believes that the written word allows us to preserve history, confront oppression, and inspire change. As a young writer, I found Coates’ words deeply motivating. There were many moments when I found myself nodding in agreement or pausing to highlight passages that felt particularly resonant. Although I was not one of his students, reading this book felt like a gift, as though he were sharing insights meant just for me. I urge others to read The Message and absorb the profound knowledge Coates has so generously shared. His reflections remind us that writing is more than a craft; it is a duty, a means of preserving truth, and a path to liberation. Through his travels and reflections, Coates shows that we each have the power to honor our past and to fight for a just future — whether by sharing stories of resilience from Senegal, standing up to censorship in South Carolina, or bearing witness to struggles in the West Bank.