Shelley Perlove, Professor Emerita of Art History

Photo by Devin Cowan, Staff Photographer

Dr. Shelley Perlove, author and Professor Emerita of the History of Art.

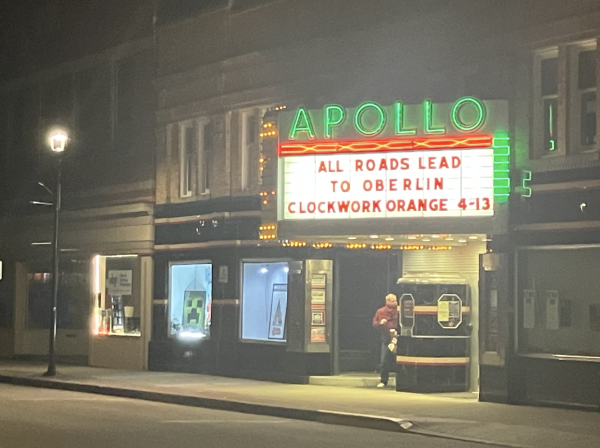

Dr. Shelley Perlove is a Professor Emerita of the History of Art at the University of Michigan-Dearborn. Her work has focused on 17th-century Italian and Dutch art — particularly on its incorporation of religious and material culture. She has published a number of scholarly works, including Bernini and the Idealization of Death and Rembrandt’s Faith: Church and Temple in the Dutch Golden Age, which won the Brown-Weill Newberry Library Award and the 2010 Roland H. Bainton Prize sponsored by the Sixteenth Century Society. She has been involved in the curation of a wide variety of exhibitions throughout the United States and the world. Professor Perlove came to Oberlin yesterday to give a talk called “Revelation in the Shadows: Rembrandt, the Jews, and Jesus,” in conjunction with the Allen Memorial Art Museum’s current exhibition Lines of Inquiry: Learning from Rembrandt’s Etchings, which was organized in conjunction with Cornell University’s Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What sparked your interest in the topic of your talk, “Rembrandt, the Jews, and Jesus”?

That’s a very interesting question, because I started out my career as an art historian. My first project, my dissertation, was on an Italian baroque sculptor and architect — Gian Lorenzo Bernini — and I wrote a book on him. I fell in love with him when I went to Rome, at the Borghese Gallery, and I saw his sculptures, and that was it. And I wrote on the Ludovica Albertoni [funerary monument], a late work by him. But then I got a job teaching. I started a museum studies program, and the basic idea was that you have to have little shows with the students, like a practicum, so they can learn what goes into the making of an exhibition. And so I was looking around to see — what can I get to put a show together? I wasn’t very successful [with] Italian baroque, but I discovered that there were quite a number of Rembrandt prints in the neighborhood at the Detroit Institute of Arts, the University of Michigan Museum of Art had some, Toledo Museum of Art had some. And I put it together into a small exhibition. And when I started working on it with my class, I realized … this is an amazing artist in the way he interprets texts and stages them. There are things that Rembrandt does with his art that no one else does. So I started doing research, and I said, “It’s not here.” So I wrote a small article on Abraham, images of Abraham. And then I got more and more into it. I had my sabbatical coming up, and I said to myself, “You know, I really want to become a Rembrandt scholar.” And then I said, “Wait a minute, you don’t know Dutch!” So then I realized I had to study Dutch. But I did it on my own, because I didn’t have time to take a class. It was very challenging, but very wonderful, and I’ve been at it ever since.

I wrote a large book on Rembrandt’s faith, about his religious works. I did a number of exhibitions. I also worked on a show on Rembrandt’s Faces of Jesus, and that opened at the Louvre, so that was very exciting. And then it went to Philadelphia, and then to the Detroit Institute of Arts. I discovered new things — there’s always new things to learn about Rembrandt. That’s why the title [of Oberlin’s current Rembrandt exhibition], Lines of Inquiry, is a perfect title for the show here. There’s always something new to discover, and I’ve been at it 20 years. And now I decided that I need to move on, so I’m working on one of Rembrandt’s pupils, Ferdinand Bol. And I thought, “Oh, I’m going to hate this, because it’s not Rembrandt. How could it be any good?” It turns out it’s really good. So I thought, “I’m on a mission. I’m going to make Ferdinand Bol famous.” He’ll never be as famous as Rembrandt, but … maybe more than he has been. He’s been neglected, Ferdinand Bol. So I’m excited about that.

As a professor, your career kind of moves from thing to thing. But I also worked at the Detroit Institute of Arts. I love museums, and at some point in my life I [had to choose between] teaching at a university or curating at a museum. So I became a professor at a university, and I continue to do exhibitions as a guest. But I love teaching, and I love students. I’m an Emerita, but I keep teaching because I care about the students.

Are the students what inspired this project for you, or was it something else?

You’re right, that’s the springboard for it. I would never think of working on Rembrandt if it weren’t for [the students.] I had to become, very quickly, a scholar of Rembrandt. So it was because of that. The necessity — they had to have a show to do. Now, this was many years ago, but some of them still write me about Rembrandt.

Did you have a teacher when you were in college who inspired you to take this path?

That’s what’s so funny. I did take some courses in Dutch art. … Maybe it was the professor, but I didn’t like it. I thought, “Oh, I love Italian art. This is not pretty enough. It’s not beautiful enough.” But it was through really being forced to study, and then Rembrandt always offers new possibilities, different ways of looking at his work. I like that because for me, as a scholar, I have to have this element of curiosity. Everything cannot be answered. If everything’s answered, I’m finished with it. I did my book on Bernini, I’m done. I’m not saying it’s the last word, but for me it was. I felt like I said what I was going to say, and I really didn’t feel that there was more for me. So I force myself into these challenging situations, but those situations, because they’re challenging, inspire me and spur me on, and force me to look at things in a different way. So I didn’t have a mentor. [In this area, I was] self-taught. It’s a little crazy, but it’s exciting. That’s the excitement of learning and knowledge.

What’s your background in Baroque art?

I think I’m a 17th-century person. I’ve written articles and a book on Bernini. I’ve written a number of articles on il Guercino, and I’m working on an exhibition on Guercino, on his religious works, because that’s what they asked me to work on. That’s what I’m known for. And then, of course, Rembrandt. I’ve done some work on Heemskerk, which you probably don’t know — he’s not really Baroque, he’s late Renaissance. And then, Ferdinand Bol. I’m on to the pupils now.

So what began your interest in the religious aspect of art?

I’ve always been interested in religious culture, especially because I don’t know anything about it. I didn’t grow up with any knowledge of religion. My parents were not very into religion at all, but I always had a great curiosity that came to me through the art. And so I would be saying, “Whoa, what is that? Why is it that? How was it used?” For Bernini, I worked on Baroque devotion, Catholic devotion. But then with Rembrandt, it was all new, because it’s Calvinism, and Arminianism, all these Protestant sects. And then also, for the first time, the Jews came into this mix, which is kind of interesting too.

Was the way that Rembrandt incorporated Jews into his work new?

[Other artists did it] but not to the extent that he did. The extent that he did was tremendous. Using Jewish models or Jews that he saw on the street, trying to give a sense of the ritual dress of Jews. They were there around him. There was no ghetto in Amsterdam. So he could really observe them, and he found it interesting, and he knew some. He saw … the Jews as the inheritors, the ones who received the covenant, and that covenant then went on to the Christians. So it was a gift, and God gave it to the Jews, and then it came to the Christians. [There are] interesting connections there. Other artists might [depict Jews], and some of them had kind of caricatures of Jews — big nose, or a traditional hat that some Jews in Europe were forced to wear, distinguishing marks like a red hat, or a yellow hat, or yellow [badges] on their bodies to identify them as Jews. But there was lots of opportunity for Rembrandt to learn from them, and he saw it. I think for him, these Jews became an archaeological [goldmine, with] unbelievable riches to plumb, to learn. [And] I’ve done a lot of work on Jesus in the Temple, so, Jesus being brought up as a Jew, his early years in the Temple.

Would you say there is any particular moment that sparked your interest in art history?

The story of my life! I was in college, and I was an English major, and I took an art history class, and I found it really difficult. I didn’t know anything about religion — so much was new. And actually, I didn’t do so well. But I loved it. I said, “I’ve got to learn more.” So I took another one, and then another one, and the young man I was going with at the time, he really liked art and he wanted me to take him to the museums and tell him about the art. So he said, “Why don’t you become an art history major?” You’re kidding me. Major in art history? And he said, “Yeah. You love it.” That was the great part. I had to convince my parents, which was a little tough. But I really thank them — they really didn’t approve, and they made it clear, but they didn’t cut me off. They said “Shelley, if that’s what you want to do, do it. We’ll pay for it.” … Some of my students will come to me in tears and say, “My parents will cut me off if I major in art history.” [My parents] used to pile up my books on the coffee table. They never read them, but they were proud.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

Please invite all the students on campus to come to see [Lines of Inquiry], and to allow a lot of time. You really have to look hard, I always say, but it rewards you every time. Every time you penetrate those shadows and you really look, it’s worth it. It gives you something. And I think that is, for [Rembrandt], a way of experiencing art. As he experiences it as a maker of art, he wants you to go through that. It’s like a discovery, a journey of discovery, of insight.