Remembering an Oberlin Legend: Joe Johnson

The 1986 Oberlin College baseball team set a program record for wins in a single season with 15. Joe Johnson, who was a legend in the program from 1984–86, broke five individual records that year.

Oberlin alumni crowded the Knowlton Athletics Complex Saturday for the homecoming tailgate and football matchup between the Yeomen and the DePauw University Tigers. At halftime, the Heisman Club celebrated its 40th anniversary by honoring select teams and athletes of the past, including all football alumni.

I hadn’t been at the game for more than five minutes when one of the former football players — a man I didn’t recognize — approached me.

Rich Johnson, OC ’88, saw the last name on the back of the jersey I was wearing and wanted to know if it belonged to my dad, a 1986 graduate of the College.

“Yes,” I responded, startled. “My dad is Brad Dill.”

“Oh my God,” he said to himself as he shook my hand. “Your dad played baseball with my brother.”

I interrupted before he could say anything else.

“Joe Johnson,” I said. “Your brother was Joe Johnson. I’ve heard all about him.”

Rich took his sunglasses off and blinked back tears before shaking my hand again.

It was true. I had heard many stories about Joe. He had an unorthodox batting stance, holding the bat sideways at a perpendicular angle to his body — similar to Jason Kipnis, a professional baseball player for Cleveland. Except Joe never straightened the bat out before starting his swing. He was an artisan at the plate, and, man, could he crush a baseball.

Joe hailed from Cincinnati, Ohio, where he played baseball and football at Roger Bacon High School. He continued playing both sports at Oberlin from 1984–86.

Although baseball was Joe’s preferred sport, the 6’1”, 205-pound man was a force to be reckoned with on the gridiron as a punter and tight end. He was an All-North Coast Athletic Conference first-team selection as a sophomore, helping the Yeomen pull off the biggest upset of the fall against nationally-ranked Denison University.

The Yeomen were on the Denison 12-yard line before a penalty pushed them back to the 31. Quarterback Jeff Andrick, OC ’85, connected with Joe, who then trudged into the end zone with two defenders on his back, securing a 23–21 win.

“He was an incredible athlete,” my dad said. “He was a catcher on the baseball team, but fielding wasn’t his forte. He was just an excellent hitter. He was a great football player too, and when we played intramural basketball together, he was a beast on the boards. He had giant calves and was 200-some pounds of pure muscle.”

My dad met Joe after transferring in from Kent State University in 1984 during his sophomore year, when Joe was a first-year. Joe was adventurous and liked to have fun, and he didn’t care how intelligent you were, where you went to high school, or how wealthy your parents were. He was interested in you. My dad was drawn to him instantly.

Joe never had it easy. His mother died from cancer during his sophomore year, and a heart attack killed his father. Joe had to be a father figure to his younger siblings, including Rich, who was a first-year at Oberlin when their mother passed.

“Joe and I danced to ‘Bad to the Bone’ in a dance contest at a party the day that his mom died,” my dad said. “He wanted to stay that night, so we did that. The next day he went home for the funeral.”

Things were vastly different back then. The Union Street Housing Complex didn’t exist, and Zechiel House wasn’t a quiet hall. In fact, it was where most of the male student-athletes lived and threw parties. The baseball program wasn’t as good as it is now, barely notching 10 wins a season.

Joe hit a league-leading .459 with 24 RBIs and two home runs his sophomore year, but the team record was 7–23.

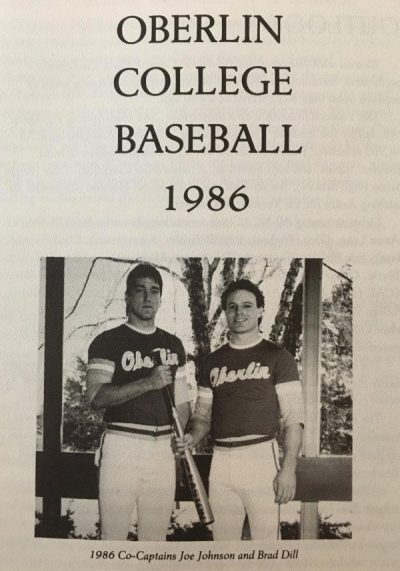

Joe and my dad were named co-captains for the 1986 season, which was when both of them began thinking the team had a chance to make school history.

“Oberlin had never been that good,” my dad said. “My senior year and Joe’s junior year was when we knew we were going to be good. We had a bunch of guys on the team who could hit. I think we hit over .300 as a team and scored eight or nine runs a game, but we had little pitching, and that made it difficult to win.”

Nevertheless, the team set a program record for wins in a season with 15. The previous record was set by the 1945 squad at 13. Oberlin hadn’t won more than 10 games in a season since 1967, and until that 1986 season, only seven teams in the program’s 100 years won 10 or more games.

Joe broke five individual records that spring, hitting .406 with seven home runs and probably would’ve hit even more had his season not been cut short by a herniated disk in his back — the same injury that kept Joe out of sports his senior year.

Don Hunsinger, an Oberlin legend who coached football, baseball, men’s and women’s tennis, and was an assistant coach for the men’s and women’s basketball programs across three decades, had the honor of coaching Joe in both baseball and football. He said he remembers Joe as a phenomenal athlete and a joy to coach.

“My favorite memory about Joe happened during spring break,” Hunsinger said. “He hit a line drive to right center so hard that he was almost thrown out at second base. If it would have been a few inches higher, it would still be going. The field had a brick wall instead of a fence, and I am almost positive that wall has a dent.”

According to my dad, if Joe had played the field as well as he hit, he probably would have been drafted.

“I used to pitch to him in the batting cages, and if you didn’t let go and get behind the screen, you were taking the ball off your shoulder or your shins,” my dad said. “I played with Division I guys at Kent State who got drafted, but Joe was the best hitter I ever played with.”

Joe wasn’t just talented. He was competitive.

“I remember one time we were playing Baldwin Wallace [University],” my dad said. “They made the playoffs every year I was in college and thought they were so much better than us. It was 1–1 in extra innings, and it was getting late and dark. Joe hit a bomb, and running down the first baseline, he told the BW dugout with two fingers that we were number one.”

My dad moved to Redondo Beach, CA, five or six years after graduation and fell out of touch with Joe.

“Guys are like that,” my dad said. “They aren’t as good at communicating as girls. But Joe was sick, so I called him one day. I wanted to see him. But he told me to wait until the spring when the weather would be better, and that he was feeling great.”

Shortly after that conversation, my dad received devastating news. Joe had passed.

“I think he died from colon cancer when he was about 28,” my dad said. “I wish I would have just gone to see him. He was like a brother.”

Joe was one of my dad’s three best friends in life. He introduced my dad to my mom Aug. 14, 1986. Without Joe, my parents probably wouldn’t have met. When Joe passed away, my dad was a pallbearer in his funeral.

It’s true that Joe was one heck of a ballplayer. He still holds the program record for career batting average at .386, is tied for first in home runs at seven, and is tied for second in single-season batting average at .459.

“A Joe Johnson does not come along every day at this level of competition, and those who never saw him hit missed a dandy display of batsmanship,” wrote then-Sports Editor Don Richardson, OC ’89, in an article titled, “Johnson’s career shortened by pain” (The Oberlin Review, April 10, 1987). “And those who did. Well, they may have witnessed the best Oberlin has ever had.”

But as good as Joe was on the baseball diamond, he was an even better teammate and friend. He loved watching pro wrestling and playing cards, and he always stuck up for the little man. He never cared about what other people thought of him, and had a heart of gold.

I wish Joe could have been at the football game Saturday, so I could have shaken his hand too.