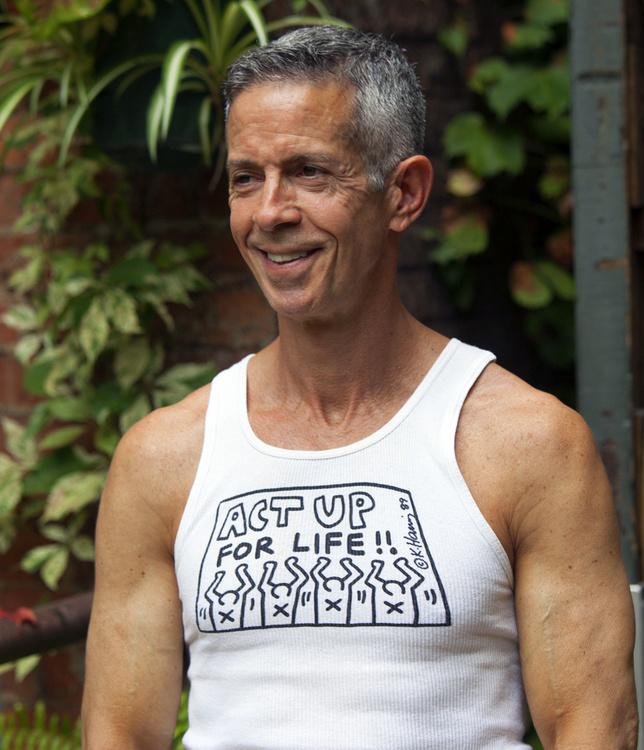

Peter Staley, Activist

Photo Courtesy of Peter Staley

Peter Staley

Peter Staley, OC ’83, is an HIV/AIDS–LGBTQ rights activist who was a prominent member of AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) and the founder of Treatment Action Group (TAG), which formed and eventually split from the Treatment and Date Committee of ACT UP. Staley is a main figure in the Oscar-nominated documentary How to Survive a Plague, which details the history of ACT UP and the AIDS crisis. Staley returned to Oberlin for his talk, “Radical Homosexuals: How ACT UP Changed the World.” Staley continues to fight for HIV/AIDS treatment, awareness, and prevention, and was a founding member of the educational site AIDSmeds.com. At the talk, Staley announced he will be writing a memoir of his life and activism.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In what ways do you think ACT UP is similar to other social movements?

We had this core group of activists, mostly the lesbians who had had quite a bit of experience in other social movements prior to ACT UP, and they brought all that movement memory into the group, so we definitely didn’t create anything new as far as the civil disobedience we engaged in. Die-ins had been done before, the civil disobedience training and how we engaged with police and how we had our own monitors — basically, people who wore special T-shirts at our actions and were the go-between between the demonstrators and the police — all of that stuff is pretty classic and borrowed from protests from the ’70s. The feminist movement of the battle for the equal rights amendment, the pro-choice movement, the anti-war movement, and of course just putting your bodies on the line is very borrowed from the Civil Rights movement. I think every new movement borrows, to an extent, from movements before it and puts a new twist on things.

Speaking of a new twist, is there anything unique about ACT UP?

I think we’re known for having combined, what we call the inside-outside gaze, very effectively, where we worked as an organization that protested in the streets, but we also demanded a seat at the table with scientists and government agencies that were making decisions that would affect our lives. And we became as expert as they were in the science and what we knew about HIV/AIDS, and the drugs that were being developed, and that kind of self-taught patient advocacy where the patient is almost as knowledgeable as the researcher. That was very new, that hadn’t quite been seen before. And the fact that we used those strategies together, demonstrating outside, insisting that we meet inside a week later, was what we were known for, and got the most bang for the buck, I think.

GG: What would you say to activists and students trying to educate themselves?

As far as learning your issue, one thing I witnessed right up close and personal [was] marveling at how a core group of the activists in the treatment and data committee of ACT UP self-taught to the point where they were able to have this discussion with Tony Fauci [an influential immunologist] about the basic science happening in his laboratory. Some of them became as expert as any Ph.D. out there, including some Nobel Laureates. So that really blew my mind and kind of taught me a lesson, that is there is no learning curve that’s too steep for young people who are very determined to climb, if you have an issue that is complex or involves science or what have you. A young activist should never feel intimidated by that, even if you haven’t studied it, even if you have no degrees in it — you can get the beginning textbooks, you can put together a study group of other like-minded activists, you can self-teach this stuff, and you will learn it faster than anybody who went through any school because you care. I was just amazed at witnessing these activists go from novices to remarkable experts in immunology and virology and pharmacology and statistics, all over the course of about two years. And it just blew my mind.

During your talk, you spoke about activists prioritizing self-care to avoid burnout. Just for people who couldn’t attend the talk, how do you recommend doing that?

Basically, what I said yesterday; pace yourself and take care of your mental health. I think this is a requirement for a good activist: somebody who is appropriately selfish about taking care of mental health. You’re really gonna be a lousy activist if you don’t. And that means, taking breaks from it for a while, and looking out for others who are doing the same work and making sure they’re taking care of themselves, too. That kind of bonding with other like-minded friends and activists around an issue — where you know the fight is hard, challenging, is mentally exhausting — but if you have each other’s backs and you don’t feel guilty about taking care of yourselves and laughing and enjoying life, even during very dark times, that’s what you have to do. That’s the only way you’re going to move the ball forward, is if you continue to try to enjoy life while you’re trying to change the world.

GG: How has AIDS activism changed since the ’80s?

Moving away from community-based activism and moving toward a more international scale. It’s definitely been institutionalized; out of what came in the ’80s and ’90s, there were AIDS organizations around the country and around the world. Many not-for-profits and institutions had positions that work in AIDS in some way, and there are community organizations [that] would often hire people to work in HIV/AIDS, so there’s this whole workforce, basically. We’re no longer reliant on a few hundred volunteers to spend obscene amounts of their free time being activists. We now have kind of a paid workforce, and from my perspective, most of them sought out these jobs because they really want to make a difference in HIV/AIDS. So, the motivation is still there, it’s still very similar, but it’s professionalized. Everyone knows everyone else, it’s international, it’s diverse, it’s finally far more representative of the affected communities that we’re supposed to be fighting for. There are far more people of color involved in fighting HIV/AIDS today and trans activists, which is just night-and-day compared to the ’80s. And all of that’s a good thing.

GG: I know you are in the process of writing a memoir. What role has Oberlin played in your life?

I’ll have it a bit [about Oberlin] straddling one or two chapters. I certainly developed my love of progressive politics at Oberlin and I honed my debating skills there, which were very helpful later on, on the floor of ACT UP. And just to be in an environment filled with young people that cared about the world. If you compare Oberlin throughout its history to many other colleges, on average, it’s always been a place where the students think about the world, care about the world, and seek to change it for the better, from a progressive perspective. I really honed that and got caught up in it while I was a student there, and it certainly helped me later on.