As Rock Climbing Enters Mainstream, Accessibility Concerns Remain

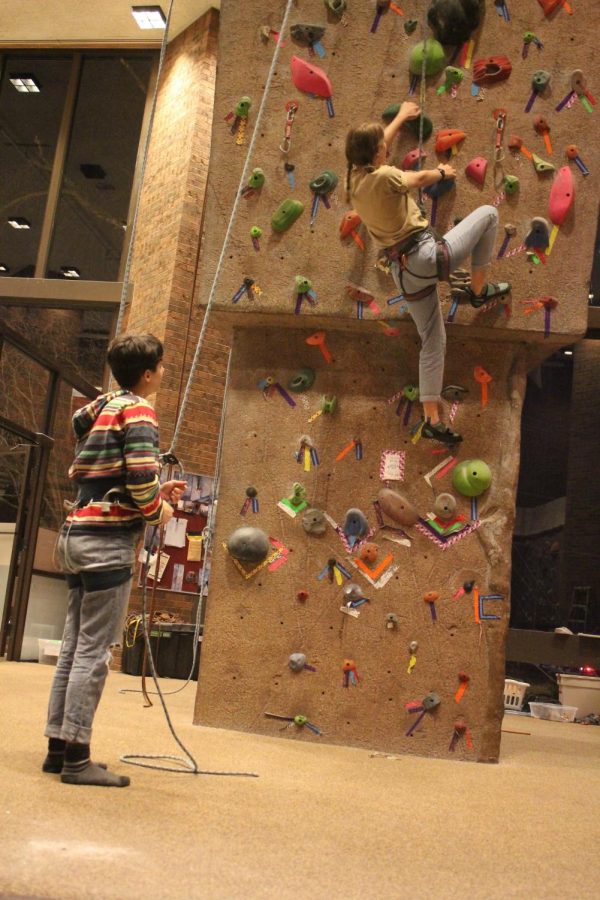

College fourth-year Julia Butler and College first-year Mira Newman at the Oberlin College Climbing Wall.

Alex Honnold’s figure is only partially visible, positioned halfway inside the deep fissure that runs through the granite wall he is scaling. He pushes steadily upwards, moving through the motions of the 3,000-foot route he knows by heart. The camera pans away from the cliff face, displaying in startling clarity the hundreds of feet of open air between his body and the valley floor below.

The documentary film Free Solo captures Honnold’s staggering endeavor — climbing El Capitan, a daunting rock formation in Yosemite National Park, without a rope. The film’s recent Oscar win in the documentary feature category marks an important milestone in rock climbing’s current trajectory. With each passing year, the sport becomes more mainstream and commercial, with the Academy’s recognition and rock climbing’s upcoming debut in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics as two prominent examples.

American rock climbing first took off in the Yosemite Valley in the 1960s and ’70s. Climbing started as a fringe sport, a counterculture movement populated by “dirtbags,” or people who have forsaken traditional employment and mainstream society for the pleasures of a rough-and-tumble lifestyle in the backcountry, scaling mountains and eating expired cat food.

Nowadays, the sport is populated by full-time professional climbers. There are film festivals, conventions, and state-of-the-art indoor gyms all dedicated to rock climbing. That small community of people dirtbagging in Yosemite has grown to become a global phenomenon.

Some climbers are unhappy with the sport’s movement into the mainstream, but Piper Triggs, College sophomore and climbing wall supervisor and treasurer, has a positive outlook on the matter.

“I think a lot of climbers are hesitant to accept it as a mainstream sport, because a lot of the foundational ideas of climbing come from the subversiveness of it,” they said. “But I personally think it’s a really cool thing.”

Despite its recent rise in popularity, rock climbing has always been inaccessible to minority and lower income groups, according to Sarah Edwards, College sophomore and climbing wall supervisor.

“Rock climbing gyms are kind of hard to come by in a lot of places and [they’re] really expensive,” Edwards said. “And learning to climb outside takes a lot of practice and training because that [requires] a lot of technical expertise.”

Triggs spoke about how certain aspects of climbing culture can discourage people from entering the sport.

“There’s a huge climbing bro culture,” they explained. “I think as the sport expands there is more space for other voices to be heard.”

College sophomore Jae Muth, climbing wall supervisor and gear and maintenance coordinator, said that the prevalence of “mansplaining” also drives some people away.

“A big part of climbing culture right now is what we call ‘spraying beta,’” they explained. “Beta” is what climbers call the advice they give for specific moves to make when climbing a route. “When men give you advice, and it’s bad advice, and you have to kind of smile and nod because they’re kind of a big deal in your gym, it sucks a lot.”

Muth described how the Oberlin climbing wall strives to be more accessible than other climbing spaces.

“One of the things I really like about the climbing wall here is that it’s free, and all the gear is free, and you can just come in and climb and we’ll teach you how to do things,” they said. “I think that’s really super awesome because in a lot of places you don’t get that.”

The climbing wall also has dedicated women and trans hours once a week, which Triggs helps supervise.

“This is my second semester working women and trans hours, and I just love the community and the solidarity,” they said. “People walk into this space and you can feel the energy of it and the kindness and the acceptance, and people really relaxing into this space. That’s incredible to watch as an employee.”

Muth spoke about the importance of creating spaces that support trans people, especially in sports. “I really appreciate the fact that it’s not just open to women but to women and trans people,” they said. “It’s super important to create a space where trans bodies can be represented and not made fun of and not commented on — especially a physical space. It doesn’t matter what your body looks like if you’re trying your hardest.”

It is also important to draw attention to the ways rock climbing’s overwhelmingly white demographic discourages people of color from entering the sport. Although a lot of rock climbing today takes place at indoor gyms, it began as an outdoor sport, and people of color have historically been barred from national and state parks. Today’s rock climbing community remains disproportionately white.

James Mills, experienced mountaineer and the author of The Adventure Gap: Changing the Face of the Outdoors, has written about the lack of diversity in rock climbing. He identifies the sport’s lack of diverse representation as one of rock climbing’ biggest barriers to POC — which is slowly changing with a new generation of young climbers.

Nineteen-year-old Olympic hopeful Kai Lightner and 17-year-old Ashima Shiraishi are two of the most well-known American rock climbers, and both are breaking into the rock climbing scene as people of color. As the popular faces of rock climbing become more diverse, it will encourage more POC to get involved in the sport.

As rock climbing enters the mainstream, more initiatives like Brothers of Climbing, Brown Girls Climb, and Color the Crag will start to pave the way for greater diversity in rock climbing and outdoor recreational sports in general. Color the Crag is a four-day outdoor climbing festival, and Brothers of Climbing and Brown Girls Climb both host meetups for people of color. All of these organizations seek to promote more diverse representation and build community among POC who are interested in rock climbing.

Ultimately, the growth of rock climbing’s commercial value marks a pivotal opportunity for increased accessibility. Alex Honnold’s feat in Free Solo was an extraordinary milestone in the sport’s history, and the national attention it won was another. Climbers like to talk about “pushing the sport,” and expanding the limits of what people think is physically possible. It’s time that rock climbers look past the next hardest climb, and set their sights on another goal: overcoming exclusivity in outdoor sports.