Reflecting On 50 Years of Africana Studies

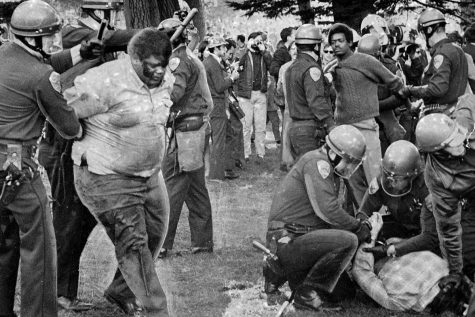

Nacio Jan Brown, Courtesy of San Francisco State College

Protesters raise their fists during “Bloody Tuesday” protests at San Francisco State College. The San Francisco Express Times ran this image on the front page of its December 4, 1968 issue.

Africana Studies Program Created Against Backdrop of National Activism

Nathan Carpenter, Editor-in-Chief

In the fall of 1969, Oberlin College launched an Afro-American Studies program, following significant student activism inspired in part by students at San Francisco State University; the University of California, Berkeley; and elsewhere. In creating the program, Oberlin joined a wave of more than 500 colleges and universities across the country that instituted similar academic departments or programs from 1968–1971.

The movement to establish what were then widely called Black Studies programs began with a November 1968 student strike at SFSU — the longest student strike in U.S. history. The strike was led by SFSU’s Black Student Union, which demanded that the university create a Black Studies program.

“Our thing was not simply to understand the world,” said Jimmy Garrett, one of the key SFSU student organizers, in a 2010 interview with SFGate. “Our duty was to change it. Everybody on the campus who identified themselves as a Black person, whether they were a student, faculty, worked in the yards, you were a member of the Black Student Union by definition.”

Garrett and Jerry Varnado are the two students widely credited with envisioning and launching the strike, which, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education, was supported by approximately 80 percent of students (“The Beginnings of Black Studies,” Feb. 10, 2006).

Officers restrain protester Donald McAllister at a strike at San Francisco State on Dec. 3, 1968

According to the same Chronicle article, written by Noliwe Rooks, now a professor at Cornell University’s Africana Studies & Research Center, solidarity between different identity-based student organizations was a key element of sustaining the SFSU strike. This solidarity led to the creation of the Third World Liberation Front, a multiracial coalition of student organizers that began at SFSU and expanded to other campuses in California.

While specific to California, the TWLF’s work became the impetus for the creation of ethnic studies programs at colleges and universities across the country — one of the places its legacy lives on is as the namesake of Oberlin’s Third World House and Third World Co-Op. Within a year of establishing SFSU’s Black Studies program, some estimate that more than 200 similar programs launched at colleges and universities across the country.

Many of these programs were supported by the Ford Foundation, which supplied grants that, some felt, were in the spirit of controlling, rather than supporting, student activism.

“The concern of the foundation was that the field would grow too much, too soon,” Rooks wrote. “[A] handful of program officers responsible for making decisions about the first round of grants were afraid that, if not properly guided, black studies would be destroyed by the sometimes conflicting aims behind it — black militancy and racial inclusion.”

Rooks goes on to argue that the foundation prioritized funding for institutions that sought to diversify white departments rather than create more black-centered ones.

“Not one of the applications for help setting up an autonomous department or program in black studies was awarded a grant,” she wrote. “For Ford, black studies was not to become a base for radical change: it was a way to foster necessary but incremental integration.”

While the Review’s archives can’t confirm whether Oberlin’s Afro-American Studies program was funded by the Ford Foundation, an issue published on June 8, 1968, does reveal that the College was “one of the 61 colleges to receive a grant from the Ford Foundation under its new program to assist humanities at the four-year liberal arts level.”

Of a total pool of $2.7 million, Oberlin received a $50,000 grant over a four-year period. The school’s intended uses for the money, as listed in the article, did not include supporting the Afro-American Studies program which would be founded that fall.

The SFSU activism inspired a similar strike at fellow California school, UC Berkeley. However, according to a 1990 study published in American Studies, consensus was much more difficult to reach at Berkeley than Garrett remembers it being at SFSU.

“Minority faculty members generally supported the idea of [a black studies program] … [but] most refused to participate directly in the ensuing strike, which began on January 22, 1969,” wrote Karen Miller, now a history professor at Boston College. “Increasingly strained relations developed between black student activists and the rest of Berkeley’s black academic community. Activists labeled them ‘cowards, fair-weather opportunists, and middle class bourgeoise [sic] pigs.’”

The strike was organized by the UC Berkeley chapter of the TWLF, which had presented the university’s administration with 14 “non-negotiable” demands — several of which centered around the creation of a Black Studies department. When the university did not initially meet the demands, students launched a strike on Jan. 22 that lasted for three months.

While Berkeley administrators eventually did agree to create an Afro-American Studies program under the auspices of its Ethnic Studies department, the implementation was so rocky that students launched a boycott of the program in 1972, protesting what they viewed to be a flawed vision for the program’s future.

While Berkeley’s program survived, many others didn’t. According to Miller, many of the Black Studies programs launched during the flurry of 1968–1971 dissolved in the late ’70s and into the early’80s. To Miller, this turbulence speaks to the ways that different constituent groups — students, university leaders, and outside funders, to name a few — viewed the role of Black Studies programs in the broader landscape of higher education.

“At best, Black Studies was represented as a panacea for higher education’s racial problematic,” Miller wrote. “At worst, Black Studies became a piece of turf on which competing political interests vied for control.”

It was against this background of student activism at SFSU, UC Berkeley, and elsewhere — in addition to significant anti-war and pro-Black Panther activism at Oberlin — that Oberlin’s Afro-American Studies program was born. While Oberlin students, like students around the country, certainly drew inspiration from their peers, campus activism here took on a unique bent, as did the Afro-American Studies program that it created.

Africana Studies and A-House Established

The construction of Lord-Saunders house in South Bowl during 1968.

Alice Koeninger

During the Civil Rights era, Oberlin College worked to maintain its image of diversity by actively undertaking large-scale efforts to recruit Black students. These efforts were spearheaded by President Robert K. Carr, who served as president from 1960 to 1970. When Black students came to Oberlin, they had trouble finding spaces where they felt comfortable. They also did not recognize themselves in the fields of study taught at Oberlin. So, in 1967, the students took charge.

“Thinking about that time, the momentum; just building off that movement was the mindset of a lot of students coming in,” said Afrikan Heritage House Historian and College second-year Deverrick McAllister. “They were just revolutionary, inspired by the movement, and the institution was also ready to accept some of these changes. It was really a student-led movement. They demanded that we have the creation of not only the house but also the department which focused on these students.”

The Oberlin College Alliance for Black Culture was formed in 1967. In a May 1968 Review article, OCABC demanded faculty develop “a relevant educational experience for the black student on this campus” (“Black Alliance Makes Educational Demands,” The Oberlin Review, May 10, 1968).

OBABC stated its goals for the organization in the same issue.

“Revamping the new educational system on this campus that will function as a double-pronged thrust at the white racist society,” members wrote. “We intend to place the black man in his proper perspective so that the black man can achieve his goal to become an educated BLACK man and so that an understanding of the black race can lead to better race relations between blacks and whites.”

OCABC wanted the administration to re-evaluate its commitment to racial tolerance, and add Afro-American Studies courses and an interdisciplinary major to the College curriculum, in hopes that that eventually an Afro-American Studies major and department could be created.

President Robert W. Fuller speaks with Black students in the early 1970s. During his tenure, Fuller tripled POC enrollment at Oberlin.

OCABC also wanted Afro-American courses such as “The Urban Black Man” to be added to the Sociology department, as well as courses on Afro-American literature and drama to be taught in the English department. Finally, they requested that a “vigorous search” be initiated by the College to recruit Black professors.

“It was really significant, the thought that Black people are worth studying, that this is something a pinnacle of higher education is going to say — that this is something valuable and worthy and you can have a degree in this,” McAllister said.

In the fall of 1968, the College approved the establishment of an Afro-American Studies program, now known as the Africana Studies program. Plans to build an Afrikan Heritage House, Lord-Saunders, were also put into effect. Until the dorm was built, places in Talcott Hall were allotted for those interested in creating a living space centered around their African heritage.

OCABC was also instrumental in the implementation of extracurricular events sponsored by the Africana Studies program, including Black Culture Week in February. A-House has a long tradition of hosting events such as Soul Sessions, art shows, poetry readings, and the Kuumba festival.

“I can talk to members of the Africana community about things that may be going on around campus, internships, family, or even about the latest song that might have come out,” wrote A-House Resident Assistant and College second-year Iesha Philips in an email to the Review. “This close-knit community and family is something that I cherish.”

Africana Studies Legacy Reverberates Today

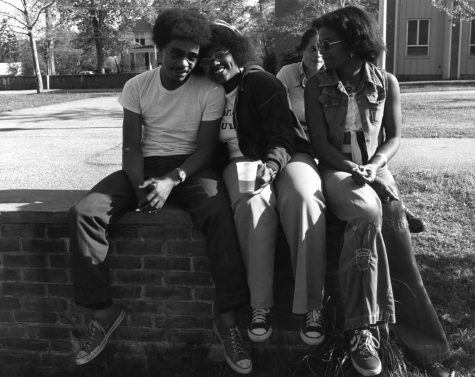

Residents of Afrikan Heritage House relax in South Bowl during the 1970s.

Drew Dansby

The history of Africana Studies at Oberlin is one of powerful activism, resilience, and solidarity. On the department’s 50th anniversary, members of the Oberlin community consider what this legacy means to them today.

“The 50th anniversary is a time for celebration, reflection, and planning for the future,” wrote Director and Faculty-in-Residence of Afrikan Heritage House Candice Raynor in an email to the Review. “[We are] celebrating and reflecting on our journey, the impact the House and department have on the students we serve as well as the greater Oberlin community, and discussing how to best move forward into the next 50 years of Africana Studies at Oberlin.”

The department’s journey is marked by student-led demands. One of the key demands in the original document by the Oberlin College Alliance for Black Culture stipulated the establishment of Afro-American House in close partnership with the academic department. The House, since renamed Afrikan Heritage House, has become a bastion of student life, featuring a campus dining hall, a library, and a resident faculty member.

“This is a place of community, fellowship, home, family, and a resource for Black students on campus,” said Deverrick McAllister, College second-year and historian-in-residence of Afrikan Heritage House. “I really appreciate the anniversary for highlighting that this is something worth celebrating.”

But the strengths of the House go beyond academic resources. For many Black students, the House has always offered a space to feel secure and explore their identities.

“It was initially instituted as a place where people didn’t have to explain themselves, somewhere they can be comfortable,” McAllister said. “It was just born out of that need to have a place where you not only fit in and are understood in your Blackness, but you’re growing in that Blackness, you have faith in that Blackness, and learning to understand its implications beyond you. I’m not really sure you could understand it if you didn’t live here.”

Students and faculty believe the opportunities for learning and solidarity the department provides have positively impacted the broader Oberlin community.

“Drawing students from all disciplines to take a course, the department is alive and poppin’,” Iesha Phillips, College second-year and A-House Resident Assistant, wrote in an email to the Review. “Its focus is to educate students about the Africana Diaspora while preparing them for the world using important skills like critical thinking.”

The anniversary is prompting members of the Africana Studies community to reflect on what future directions the department might take.

“In the future, I hope to see more collaborations with other cultural programs,” Phillips wrote. “I know we have been doing more Afro-Latinx events, so that makes me happy. I also want to see more funding going into the house for things like a basketball net and pool table because Afrikan Heritage House is the hub of Black life on campus. It’s not only a safe place, but a place that values community.

McAllister says he wants to see Oberlin administrators make the Africana community on campus more visible.

“I’d really love to see an African language taught here at the College, or even something like Portuguese that’s used in Brazil,” he said. “I’d [also] love to see tours. Tours don’t come down [to A-House]. Like even just to walk down and say, ‘it means this to students here, and you have a place here.’”

To celebrate the anniversary, Professor Raynor is hosting a few special events at A-House this academic year, including two panel discussions during Black History Month and a festival in the spring. Raynor also writes that she will plan annual programming on a grander scale this year. Some upcoming programming includes Kuumba Week starting on Monday, Kwanzaa in December, and Black History Month in February.