From Oberlin High School to Kendal: Climate Activism Across Generations

Richard Payerchin/The Morning Journal

High school students rally at last September’s Climate Strike.

Looking back on his decades of climate activism, Vice President of Communities for Safe and Sustainable Energy John Elder, OC ’53, remembers that his passion for environmental activism grew out of his childhood love of the outdoors.

“I was ingrained with an appreciation of our oneness with the environment,” he recalled.

The activism of Oberlin High School Sustainability Club President Sacha Brewer has different roots: a recognition of the pressing need for action in the face of the global climate crisis that her generation inherited.

“I think that I really got into [activism] my junior or senior year with … Greta Thunberg and a lot of young climate activists coming out, and I think that was definitely a big push for me,” Brewer recounted. “And then I saw a lot of people … push aside environmental legislation, and I [thought] I need to stress this. I need to put my all into this.”

The different generational motivations for environmental activism reflect a growing desperation for climate action that is felt across generational lines. However, this desperation has profoundly shaped the perspective of younger activists who have come of age in a time of crisis. It also has broader implications for the methods of activism taking shape within and across generational lines. Brewer, for her part, sees the climate movement as primarily led by youth around the world.

“I think that it’s important when these movements are led by young people because we’re the ones that are ultimately going to be affected by it,” Brewer stated. “I think that young activists now have done a really good job in influencing other young people to come out and speak about it — [they] have given young people power in that.”

Brewer, along with other members of the Sustainability Club and Sunrise Oberlin, organized a walkout in coordination with the Global Climate Strike this past September. The goal of the strike was to raise international awareness for climate justice and push for national legislative action in the form of the Green New Deal, a framework grounded in justice and equity and encompassing all areas of policy. The strike also featured several activists, including Brewer, who spoke with infectious passion about their personal relationships to climate change and why they believe the Green New Deal is not only possible to achieve, but necessary for survival. (Event organizer Faith Ward’s opening speech is included in this issue, edited for length and clarity, on page 8.)

While this style of energetic mobilization aimed at increasing pressure on national leaders has been prevalent among young organizers, many adults with decades of experience in environmental activism feel that it isn’t enough.

Oberlin City Councilmember and Director Emeritus of Libraries Ray English, while generally supportive of striking, believes that direct efforts to change legislation should be the main target of climate activism. From his perspective, the only way to move such legislation forward is through bipartisan cooperation.

“If someone wants to be part of a strike for climate change … that helps raise the issue,” English said. “The more our country is aware of the issue, the more likely it is that we will actually deal with it. But for me, it all comes down to [this]: We simply will not deal with this issue unless [we] can get effective legislation through Congress.”

As a result, English’s activism has largely taken place with the Citizens’ Climate Lobby, an organization which lobbies congresspeople of both major political parties to support more moderate climate legislation.

“In getting into CCL, I saw an organization that potentially … could get a bill through Congress that could be really effective,” English said. “It could be bipartisan, that is, have enough bipartisan support that in a future Congress — or with a different president — you wouldn’t run the risk that the other party would try to undermine it. For me, climate change is simply too important — it’s an absolutely critical issue.”

CCL primarily champions the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act, which grew out of the bipartisan Climate Solutions Caucus. The CSC currently includes 64 members in the House of Representatives, including 24 Republicans, and 14 members in the Senate with equal representation from both parties. The caucus, which CCL is largely credited with creating, introduces a version of the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act in every session of Congress. The bill aims to combat climate change by imposing a steadily increasing fee on carbon emissions, paid by upstream polluters like coal companies, in hopes of making fossil fuels economically uncompetitive and encouraging green alternatives. The revenue from the carbon tax would be distributed directly to households in the form of a monthly “dividend.”

However, other activists such as Elder see instability in this approach, citing the disintegration of the CSC in the House after most Republican members of the caucus lost their seats to Democrats in the 2018 midterms. The vast majority of Republicans that remain in Congress reside in gerrymandered, safe Republican seats. Their biggest electoral threat is not a Democratic challenger who could criticize them for denying climate change, but a Republican primary opponent whom they could invite by crossing the powerful fossil fuel industry. Even though 24 Republicans remain in the CSC in the House, only one is actually a co-sponsor of the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act. This points to a broader issue: Republican support for climate action is extremely tenuous, and trying to attract bipartisan support for serious climate legislation is a near-impossible task.

“The Republicans [in the Climate Solutions Caucus] lost their seats, and the climate change deniers won,” Elder remarked sadly. “But the fact that there is that national organization with the focus on getting bipartisan support of a carbon tax is a good thing.”

Despite his skepticism of CCL’s bipartisan approach, Elder concurred that legislative change should be the crux of climate activism. In his eyes, local politics presents an opportunity for effective organizing and real climate action.

“When you come down to the nitty-gritty, small change of saving the environment, it means working on detailed legislative projects and getting voters out at referendums and ballot issues and so forth,” Elder said. “And that gets very complicated and takes a lot of work door-to-door calling … and attending boring city council meetings and so forth.”

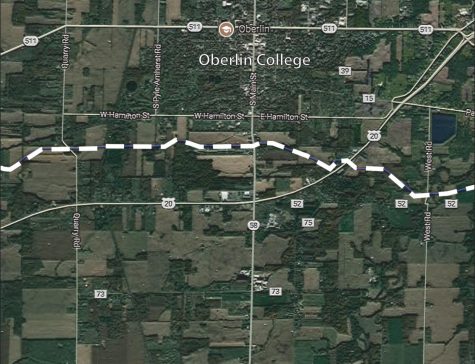

During his years in Oberlin, Elder has contributed to many local environmental groups in connection with the College, Kendal at Oberlin, and First Church in Oberlin. Most notably, Elder co-founded Citizens for Safe and Sustainable Energy in 2012. Through CSSE, he has successfully advocated for a local initiative known as the Sustainable Reserve Fund, which seeks to lower carbon emissions by subsidizing energy efficiency projects in low- and middle-income households. CSSE has also been active in opposing the NEXUS pipeline, which travels through Oberlin. (A history of the pipeline, and local opposition to it, is included on page 18 of this issue.) These achievements are concrete and enshrined in law, but they are undeniably much smaller in scale than the kind of change that Brewer and other youth activists are calling for.

Despite the tactical differences across generational lines and between activist groups, all three of these local leaders highlight the role of unity and collaboration in climate work — whether among young people, as Brewer outlined; within local communities, as Elder described; or between political parties, as English advocated for. Interestingly, none emphasized the importance of intergenerational collaboration.

For Brewer, however, a simple conversation could be all that’s needed to initiate such allyship.

“I just would say to older activists to help encourage younger activists, because I know that burnout is a real thing, and [older] activists definitely know about it,” Brewer said. “So I think that [they could] just [be] encouraging [to] younger people, just by even sitting down and talking to them, inviting them for conversation. It should just really be about unity, you know — we love the earth, that’s a beautiful thing. We should get together and fight for it.”