Q&A: Mary Annaïse Heglar, OC ’06, Climate Writer

Photo courtesy of Mary Annaïse Heglar

Mary Annaïse Heglar.

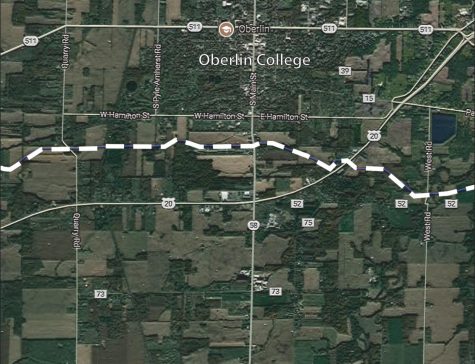

Mary Annaïse Heglar, OC ’06, is a writer who focuses primarily on personal essays about the intersections of climate and justice. She also serves as director of publications for the National Resources Defense Council, and is currently a writer-in-residence at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, where she is working on both short- and long-form pieces about climate change and its human impacts. Recently, Heglar has published on the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ways that grief over its spread mirrors her own journey through climate grief. Heglar claims the Gulf Coast as home and has written extensively about climate within that geographic context, including her reflections on Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall right before her senior year at Oberlin. Heglar is a speaker and panelist in several virtual events taking place this week as part of Oberlin’s Earth Day 50 celebration.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I was hoping you could start by talking about what initially drew you to write about climate change and climate justice.

I’ve always worked in nonprofit communications, and that led me through the arts and higher education, and eventually I was doing work with a social science research foundation. I decided I wanted to work on something that was more immediate, and I wanted to be part of telling the most important story. At the time, I decided that [story] was climate. So that was how I came to climate communications in particular. So my job at NRDC, I’m now the publications director, but I started as a policy publications editor. That means that you’re working with these really wonky, really dense and technical reports about environmental damage, mostly, and how to solve it. And it’s terrifying. It was really, really terrifying. I ultimately came to a place where I was like, “Well, I need a place to process my feelings about this stuff.” That was what drew me back to writing because it’s the best way I know how to process anything.

Were you thinking about this stuff while you were at Oberlin or does your current work in any way have roots in what you were doing while you were a student here?

It definitely related to a lot of stuff I did at Oberlin, which I didn’t recognize until much later. I don’t know if y’all still do The Word ’n’ The Beat festival. Does that still happen?

I don’t think so. Maybe it has a different name.

Maybe. It was still active up until like two years ago or something, with [Professor of Theater and Africana Studies] Caroline Jackson-Smith. I bring that up because, immediately when I got back to Oberlin after [Hurricane] Katrina — that was right before my senior year — I wrote a poem about Katrina, and Katrina as Emmett Till. And that was how The Word ’n’ The Beat started. At the time I wasn’t thinking of Katrina as climate , but I’ve got a whole-ass essay out here about Katrina now, so I guess so. So I’ve been writing about Katrina ever since Katrina happened. … Also, when I graduated, I thought I was going to be a journalist and I did a summer at Oberlin with [John C. Reid Associate Professor of Rhetoric and Composition and English] Jan Cooper. Is she still there?

Yeah, Jan’s still here.

Jan kept me on as her student assistant over the summer and she was really interested in how environmental journalism was shaping up. She had me do all this research on it, so that she could use it to teach her class next semester. So yeah, [I] didn’t know that that was going to become super pertinent.

What do you think makes an essay about climate change particularly compelling?

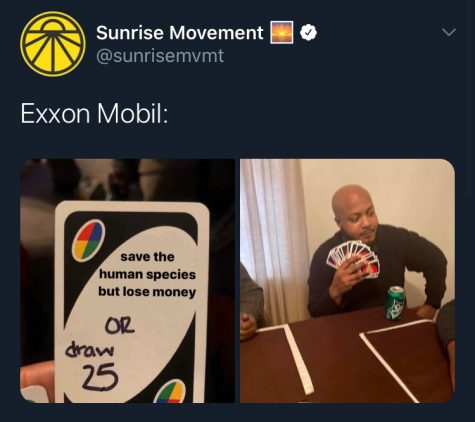

To me, what’s compelling is the truth, and the whole truth. I think we’ve been not so good at telling it. I say that in terms of naming the villain; we’ve really been bad at connecting the dots to the fossil fuel industry. We sort of, as a community, have made it seem like climate change is just this thing that happens, and that to fight climate change you gotta go fight the air. No, we should fight the fossil fuel industry, and then it’s tactile, something you can do. So I’m drawn to communications that name the villain. I’m drawn to communications that allow space for emotional messiness, and that have a good bedside manner. I do think the reports that I was editing at NRDC, they’re important, and they should be technical and they should be wonky, but that’s when an expert is talking to a decision maker. That makes sense. But when we’re talking person to person, that sort of cold, clinical language doesn’t work. You try to fact people to death and that doesn’t work either. And actually, we’ve talked about climate change like it’s just this really, really complicated thing. It’s not. It’s really simple. It’s an injustice: bad guys versus everybody else. It’s like a classic story.

Similarly, what have you found — maybe in your own writing or reading other people’s work — are the biggest challenges in writing about climate?

The biggest challenges are gatekeepers. At these big publications, there [are] a lot of editors who are really stuck in their ways and kind of feel like, “We know how to do this.” What I think is, “You don’t; if you did, it would’ve been done already.” … So I think that’s a big barrier. And I think, up until recently, there were a lot more and I think 2019 saw a lot of really important conversations in climate really get litigated. For example, individual versus collective action. For a long time, [climate action was seen] as the one thing you can do, which is like recycle your plastic bags or something. And that got interrogated last year and I think that narrative is out. There was also the narrative that people of color don’t care about climate change; that myth got busted. So if you had asked me a year ago, I would’ve been able to name a lot more problems, but I feel like now, a lot of those barriers have come down.

To shift gears a little bit: You cite James Baldwin as your personal hero, and I’m wondering if you could talk a little bit about why.

I love James Baldwin for so many reasons. One, he was a fantastic writer. He had a really strong gift for naming beyond names, and describing things that you had felt before but never really had the language to articulate. That is basically giving you the weapons, the tools to dismantle your oppression — when you can finally articulate it, then you can change it. I think that’s a quote of [his], it’s like, “You write in order to change the world.” If you alter the way people see reality, then you can change it. I thought he just was amazing at that. Another reason I admire him so much is because he really loved children and youth and he took them very seriously. … There are lots of video interviews that he does, [and] whenever he’s talking to a teenager or a young person, he’s always very interested in what they have to say, and takes them seriously. … Stokely Carmichael, who was a teenager when James Baldwin was in his thirties or something, they had a great mentorship relationship because James Baldwin always showed up for them, took them under his wing.

Obviously, during the time in which James Baldwin was writing, people weren’t necessarily talking about climate change in the terms that we do today.

No, not at all. I don’t think it had been discovered.

I’m wondering if there are still lessons that younger writers can take from how James Baldwin approached his own writing that you think are applicable to writing about climate and the environment, even though that wasn’t what he directly focused on.

Well, yeah. I take a lot of my cues for writing about climate from him. I try to find something that I don’t think has been articulated well and really grapple with it, so not being afraid of messy ideas. The point of writing, I think, is to come to a conclusion. I think a lot of people feel like you have to know where you’re going before you start, and you don’t. That’s not the point of writing a personal essay, at least — it might be the point of writing a term paper. He was never afraid of foggy ideas, or at least didn’t seem that way. And I think that the climate crisis is the outgrowth of not really healing the wounds of Jim Crow or slavery or etc., and that way his writing [makes] a very seamless connection.

If you were to be speaking to a room of students who are interested in writing about climate and the environment after they graduate, what’s some advice or words of wisdom that you would give them?

Maybe don’t expect it to be a full-time-paying gig at first. Not if you want to be good. Because if you make it your source of income, you’re kind of beholden to editors. You might wind up having to write something that you don’t fully believe in, and if you don’t believe in it, I don’t think you should write it.