Reflections on Third-Year Responses to Oberlin’s Trimester Plan

In my position as This Week editor, I collected and published data from fellow third-years concerning how they felt about the College’s three-semester plan. While processing the responses, I reviewed over 61 perspectives and noticed several commonalities that I would like to emphasize in assessing the plan’s success for third-year students. Further, I will delve into my personal experience of the three-semester plan thus far.

In survey responses, students accused the College of choosing money over the best interests of its third-year students, and several felt that third-years were asked to make the greatest sacrifice because they would be less likely to transfer than their younger peers. This life-disrupting plan felt particularly difficult to some, as it comes in wake of a universally traumatic spring and summer and feeds right into post-grad life without any months-long break. Some students questioned why Oberlin chose not to follow in the footsteps of other schools and ask all students to do one virtual semester, or allow third- and second-years the option to enroll virtually during their off-campus semester. While the three-semester plan’s ostensible goal was to preserve the quality of on-campus education, some students felt that collecting housing and dining money was a major factor behind this choice.

With fewer class offerings and therefore more scheduling roadblocks, students also worried that the trimester plan hurt their academic prospects and could delay their graduation. The Junior Practicum was case in point: inaccessible to many, yet the only way for students to earn Winter Term credit. Only after students endured a protracted struggle to balance the Practicum, work, and personal life did the College begin making exceptions.

Though the Junior Practicum successfully supported many students, connecting hundreds with virtual micro-internships, the experience wasn’t optimal for all. Students mentioned that the $800 ($300 extra for pitch competition winners) stipend — contingent on completing both the month-long practicum and the subsequent internship — was not enough money for the commitment, especially as it came for many at the expense of higher-paying or consistent work. Despite the Practicum’s merits, some students expressed disappointment about lost summer opportunities beyond Oberlin. With the proliferation of virtual and remote-accessible classes at Oberlin, the need for an on-campus experience for every College third-year appears dubious, especially for the price of other summer 2021 opportunities.

Personally, I would have to say no, the trimester system wasn’t good for me. I had to work nonstop through the summer into the fall while dealing with school obligations — without the food and housing security that the school offers. I did the Junior Practicum because it was the only Winter Term option, which meant, when accounting for my other responsibilities, working 10-hour days Monday through Friday.

I had to be on Zoom from 12–5 p.m. and work at a restaurant from 4–10 p.m., usually later. The overlap meant that I had to participate in the practicum while getting ready for work, in my car while commuting to work, in the parking lot outside of work, in the bathroom at work, in the breakroom at work, coming back to my device in between serving tables and making salads and washing dishes. Working the same shifts on the weekend meant I could barely catch my breath even when practicum ended for the week. It was exhausting. That’s what some students are doing while their cameras are off.

At least having a job kept me out of the house. While negotiating the practicum, the subsequent internship required for full compensation, and my job, I was dealing with serious at-home conflicts that forced me to spend nights in my car until I could move in with a friend. When I was sleeping in my car, I wished I had the security of the Oberlin housing I thought I could rely on for every fall of my college career. As a guest in my friend’s home, Oberlin’s choice to extend the break through January strained my living situation, and I wound up overstaying my welcome. I had to pick up another job to get me through my time off campus.

Looking ahead, I am far less concerned about staying on campus until graduation because at least I will have a place to stay this summer — in fact, if I could choose any place to be most summers, it would probably be Oberlin with my friends. I am a nerd who took elective summer school classes because I always thought the break was too long and boring. I think ultimately I am going to have a lot of fun on campus this summer. I am excited.

But I am also concerned, as this is the last summer I have before graduation to take advantage of programming, workshops, and internships that can help me prepare for post-grad life. Junior Practicum was supposed to provide an opportunity for career readiness comparable to my lost opportunities, but by the summer almost a year will have gone by since September 2020. I’ve matured personally and academically since then and primed myself to take advantage of my final pre-grad opportunities, especially those beyond academic life in Oberlin’s classrooms. Last year, I lost my summer to COVID-19, and this year I’m going to lose my summer to Oberlin’s aberrant academic calendar.

When I look at the data and my own experience, I see a few clear recommendations for Oberlin: loosen the criteria regarding transfer credits, implement flexibility and listen to student feedback across all academic departments (and Winter Term) in order to ensure timely graduation, and adjust syllabus policies to relieve pressure around midterms and finals. I also insist there be a greater effort to keep up with and support current second-years, who usually depend on Oberlin for housing this time of year and now may be without a secure place to stay.

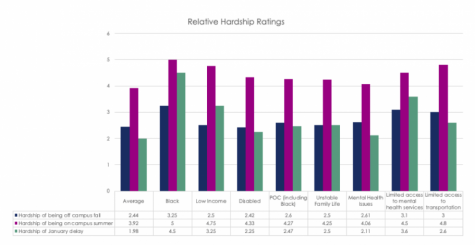

As a third-year, it seems clear to me that damage has been done disproportionately to my class. Although I know that this has been an arduous process, there is still much that Oberlin must do for third and second-years in order to fully support them through the trimester plan — just as they took care of first-years, fourth-years, and Conservatory students. According to the data I collected about hardship, students from marginalized communities, such as Black students like myself, were affected to even greater extents and should receive proportional assistance and influence in solving these issues.

Students who are enrolled for the summer term are worried they will feel alienated from their friends, families, and the larger sphere of academia, and there is almost universal concern for burnout as third-years face four consecutive semesters. Although the school is facing a financial crisis made worse by the pandemic, we cannot forget that individual students are affected by this as well to differing extents.

I don’t know for sure why the trimester plan was chosen; I think that the option to enroll remotely during the normal academic year instead of a mandatory summer semester would have been more equitable. If the many survey respondents are correct and room and board money was a motivating factor in this trimester plan, then this money is coming straight out of the pockets of some of Oberlin’s most vulnerable students, and at the expense of many people’s academic and emotional well-being. This directly defies Oberlin’s message of social justice.