Oberlin Falling Behind in Faculty Compensation Before COVID

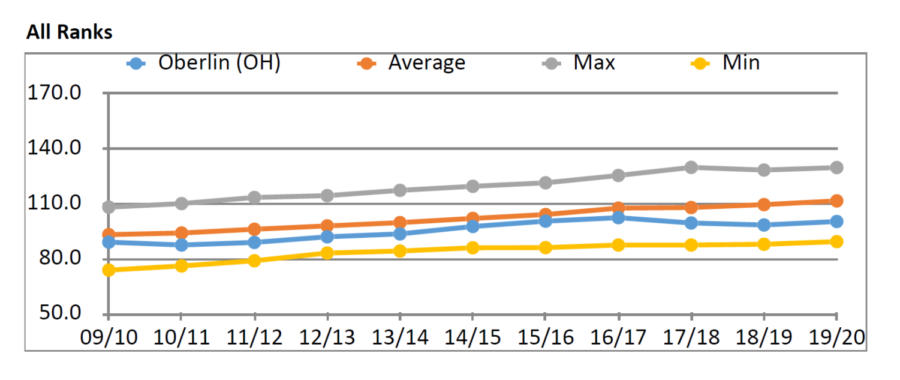

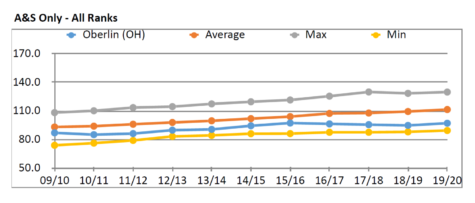

Some professors have criticized Oberlin’s compensation rates, pointing out that faculty salaries don’t stack up against those at competing institutions. Before the pandemic, Oberlin’s total compensation was ranked 15th out of our 17 peer institutions and has lagged below the median for the past decade, according to the General Faculty Compensation Committee’s Annual Report on Salary and Total Compensation.

The committee’s report compares Oberlin salaries as well as total compensation — which includes retirement and healthcare benefits — to a group of 17 peer institutions. Although Oberlin salaries ranked 15th overall for the 2019-20 academic year, assistant professors ranked 16th while professors and associate professors both individually ranked 14th. Overall, College professors also tend to be paid less than Conservatory professors — when College faculty salaries are isolated, professor and associate professor salaries rank 15th.

(Annual Report on Salary and Total Compensation)

Professor of Mathematics Jeff Witmer says that, during his 35 years of teaching at Oberlin, compensation has always been a hot-button issue for faculty.

“It’s been an ongoing issue,” he said. “I can’t remember a time when it wasn’t something that faculty talked about. It’s just always there.”

There are a few schools among the peer group that Oberlin would have a hard time competing against in terms of faculty compensation, according to Witmer.

“Grinnell, Swarthmore, Pomona, and some other schools have much bigger endowments than we have,” Witmer said. “It’s a difficult comparison group to be in because we don’t have the same financial resources as some of these other schools.”

But not every school is significantly better-funded than Oberlin, and the College’s low standing is concerning to Witmer. In particular, he worries about assistant professor salaries.

“We’re not in last place — we’re ahead of Kenyon, but Kenyon is gaining on us pretty consistently, and they’re going to pass us pretty soon the way that’s going,” Witmer said. “And then we will be in last place among this peer group.”

2013 Resolution for Competitive Faculty Compensation

In June 2013, Oberlin’s Board of Trustees resolved to reach at least the median compensation level among its peer institutions. The board launched a five-year plan to increase salary pools, including matching some peer institutions’ annual raises of 4 percent. Oberlin rose through the ranks from 14th place in 2011-12 academic year to 12th place in 2014-16 academic years. But three years into its five-year plan, the College abandoned this effort and instituted a two-year wage freeze for faculty and administrative and professional staff. This move sparked outrage among some faculty members.

“The results are entirely predictable, and will be poor,” Nathan A. Greenberg Professor of Classics Kirk Ormand and James Monroe Professor of Politics Chris Howell wrote in a Dec. 2017 Letter to the Editor. “Our salaries will drop to near the bottom of our peer group within two or three years, and we will remain there as a matter of financial strategy. Hiring and retention will suffer. Our best early-career faculty will leave, as several have over the past three years. Morale will plummet.”

The two-year wage freeze was enacted while the College developed the One Oberlin plan to address Oberlin’s structural deficit, which was expected to amount to $162 million by the year 2028 if the College didn’t take action.

Although the board’s five-year plan was halted, Chair of the Board of Trustees Chris Canavan, OC ’84, says that faculty compensation is a vital issue to Oberlin’s leadership team.

“The board — and I know that Carmen shares this view — believes that the most important reason that students come to Oberlin is because of the faculty,” Canavan said. “That’s why you go to college; to interact with this amazing group of scholars and teachers and thinkers and doers who deliver the core of the Oberlin educational experience.”

According to Canavan, the board’s strategic plan for increasing faculty compensation was unrealistic because it did not articulate a plan for new revenue to support salary growth.

“The declaration in 2013 essentially said, ‘Let’s increase one slice of the pie,’ but was silent on which other slices shrink as a result or how you make the pie bigger,” he said. “We can’t afford that kind of thinking.”

President Carmen Twillie Ambar says that she hopes to create new revenue for faculty compensation through efforts like the One Oberlin plan.

“This doesn’t happen because we just plug some numbers in a model,” President Ambar said. “This happens because we can upend the model — we can generate more revenue, bring in more students, have a different value proposition that makes the pie bigger.”

Oberlin’s Financial Challenges and Endowment

Even before the pandemic created additional financial pressure, the College was already facing a significant structural deficit. Still, there has been some good news this year. Last June, the College anticipated a one-time deficit of $44.7 million in pandemic-related expenses, but its most recent estimates fall in the range of $13.5 to $20 million. And in November, the College’s endowment surpassed $1 billion for the first time in Oberlin’s history.

These developments are a sign to Ormand that the College could be doing more for faculty compensation.

“For the first time in Oberlin’s history, our endowment had crossed the $1 billion mark,” Ormand said. “So our endowment’s doing fine, but that’s happening at a time when, for three of the last four years, we’ve had no raises. In one of those four years, we had a 2 percent raise, but it was combined with a 16 percent cut to benefits, which amounted to a net loss in income for most of us.”

This year the College initially announced a wage freeze for faculty and staff — but after receiving improved budget projections, the College enacted a 2 percent, non-base pay raise that won’t apply toward employee salaries next year. The College also suspended retirement contributions with the goal of reinstating retirement benefits for the 2020-21 academic year. None of these measures are reflected in the most recent committee report, which only captures pre-pandemic data.

“It’s an emergency, I get that,” Ormand said. “But when you combine the fact that we’ve stopped retirement contributions for faculty, with the fact that our endowment seems to be performing at a record level — wait a minute, right? My retirement fund, that’s my endowment. And so what the College has said is, ‘The College’s endowment is more important than your endowment.’ Okay. You can tell me that, but what you’re really saying is that the endowment is more important than the employees who have given their lives to this institution.”

The College is currently working to reduce the percentage that it draws from the endowment annually. Even so, Vice President for Finance and Administration Rebecca Vazquez-Skillings expects that the College will see higher returns if the endowment maintains its current growth.

Still, Canavan says that the endowment is not the answer to competitive faculty compensation.

“We already take more from the endowment than I think we can comfortably, especially when many people expect lower returns in the markets — and especially now that we’ve discovered how important it is to have an endowment to absorb shocks like the one that we’ve absorbed over the past 12 months [due to the pandemic],” he said.

According to Canavan, the College’s decisions surrounding faculty compensation are driven by the financial challenges presented by the structural deficit and the pandemic.

“We would like nothing more than to change the trajectory of faculty compensation,” Canavan said. “We hope that we can make adjustments to the financial model in a way that allows us to invest in the faculty, but we must do that within a framework that we know is sustainable over the next generation.”

Debate Over the College’s Spending Priorities

For Ormand, when major campus initiatives are funded while salaries fall behind, the issue of faculty compensation comes down to the College’s spending priorities.

“What they’re telling us now is we have a structural deficit, and the only way to address it is through salaries because close to 70 percent of our annual budget was in the form of salaries,” Ormand said. “We have real constraints. I understand that. On the other hand, I can point to areas where we’re willing to spend money. … Both the sophomore and the junior Winter Term programs this year included $800 stipends for all the students who participated in SOAR and in the Junior Practicum. The President just announced a new $140 million dollar rebuilding of our energy plant. Those are all reasonable expenditures, and the energy plant is absolutely necessary. But when the College can find $140 million for our physical plant, but can’t find $800 thousand to give the faculty a competitive raise, it makes the administration’s priorities crystal clear.”

President Ambar believes that investing in key programs that improve enrollment — such as student internships funded through the Career Development Center — must be prioritized because they generate new revenue that can eventually be applied toward faculty compensation.

“Our lack of willingness to invest in things like internships, undergraduate research, and all of those pieces for students has hurt us in admissions,” President Ambar said. “And that’s the very place that we can solve our challenge, right? The revenue generation associated with students choosing Oberlin. So to say to me that you don’t think we should invest in stipends for students, I would say would be cutting off your nose to spite your face.”

Still, Ormand believes that the College should look at shifting its budgeting priorities toward faculty compensation sooner, based on the current salary trends. Non-competitive salaries can make it more difficult for a College to hire and retain strong faculty members, something that directly impacts an institution’s academic excellence.

“Faculty — especially faculty who don’t yet have tenure — are highly mobile,” Ormand said. “If we’re not paying well, they leave. … Some of the [faculty] that we’ve recently lost I think were some of our most promising pre-tenured or recently tenured professors. … I also think it’s hurting our diversity efforts because every college in the country right now is scrambling to hire and retain underrepresented minority faculty, for good reason. And when we’re not paying competitive salaries, those professors can go elsewhere.”

Claire Solomon, OC ’98, Associate Professor of Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Chair of Hispanic Studies, and president of Oberlin’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors, says that she has seen many professors leave Oberlin for schools that can offer better salaries and benefits.

“We lose colleagues every year and that is depressing,” she said. “It’s hard for our curriculum because we want to staff in a consistent way — we want to build communities in our departments and programs and build lasting relationships between students and faculty. And I think for students it’s really hard when there’s a bond with a faculty member who leaves. And so that’s kind of the big thing for me. It really puts a dent in our ability to create a lasting community.”

Ormand wishes for more transparency surrounding the College’s plans for faculty compensation.

“If our strategy going forward is that we’re just going to underpay the faculty by 20 percent, our faculty should know that so that people who want to go elsewhere can,” Ormand said. “I know for a fact that I could be making 20 percent more teaching elsewhere. Add that up over 10 years, it turns into real money.”

Ormand says that he understands pandemic-related challenges this year — it’s the pre-pandemic trends that concern him.

“I think every college in the country has had wage freezes and benefits cuts this year because everyone’s kind of scrambling,” Ormand said. “I get that. But the report — that’s all pre-pandemic data. Starting from the minute that the board abandoned their plan of trying to improve our salaries, we started moving down.”

Ormand pointed out that Oberlin ranked 3.5 behind the average for all faculty salaries in 2015-16, and has since fallen to 10.1 percent behind the average.

For Solomon, the issue of competitive compensation comes down to ensuring that faculty have the peace of mind to focus on their work. She says that discussions surrounding the possible reduction of faculty healthcare options to a high deductible plan and the outsourcing of the College’s unionized custodial and dining employees have deeply concerned many faculty members.

“I would just like the senior staff to hear us in that this is not about wanting to have more money to buy more stuff,” Solomon said. “It’s about having the luxury of not worrying about retirement, healthcare, or salary so that we can just focus on doing our jobs.”

Witmer would like to see a concrete plan put in motion to prioritize competitive faculty compensation, but also emphasized that the structural deficit, COVID-related deficits, and the pandemic’s disruption to enrollment make this particularly challenging.

“We don’t know how we’re going to emerge from the pandemic,” Witmer said. “It’s just a really uncertain time for the trustees to be saying, ‘Here’s a 10-year plan about what to do,’ because the financial picture is just so blurry.”

The Compensation Committee expects to present its report for the 2020-21 academic year in a General Faculty meeting this fall, which will show the pandemic impacted Oberlin’s rank within the peer group. The AAUP has reported that average faculty salaries increased by only 1 percent this year, the smallest increase on record since AAUP began tracking annual raises in 1972.